The U.S. has approved the world’s only twice-a-year shot to prevent HIV, its maker Gilead Sciences announced Wednesday.

It’s the first step in an anticipated global rollout that could protect millions — although it’s unclear how many in the U.S. and abroad will get access to the powerful new option.

While a vaccine to prevent HIV still is needed, some experts say this medication — a drug called lenacapavir — could be the next best thing. It nearly eliminated new infections in two groundbreaking studies of people at high risk, better than daily preventive pills they can forget to take.

“This really has the possibility of ending HIV transmission,” said Greg Millett, public policy director at amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research.

Condoms help guard against HIV infection if used properly, but something called PrEP — regularly using preventive medicines, such as the daily pills or a different shot given every two months — is increasingly important.

Lenacapavir’s six-month protection makes it the longest-lasting type — an option that could attract people wary of more frequent doctor visits or stigma from daily pills.

But upheaval in U.S. health care — including cuts to public health agencies and Medicaid — and slashing of American foreign aid to fight HIV are clouding the prospects.

Millett said “gaping holes in the system” in the U.S. and globally “are going to make it difficult for us to make sure we not only get lenacapavir into people’s bodies, but make sure they come back,” even as little as twice a year.

Gilead’s drug is already sold to treat HIV under the brand name Sunlenca, which is listed as approved in Health Canada’s database. The prevention dose will be sold under a different name, Yeztugo. It’s given as two injections under the skin of the abdomen, leaving a small “depot” of medication to slowly absorb into the body.

Gilead didn’t immediately announce its price. The drug only prevents HIV transmission; it doesn’t block other sexually transmitted diseases.

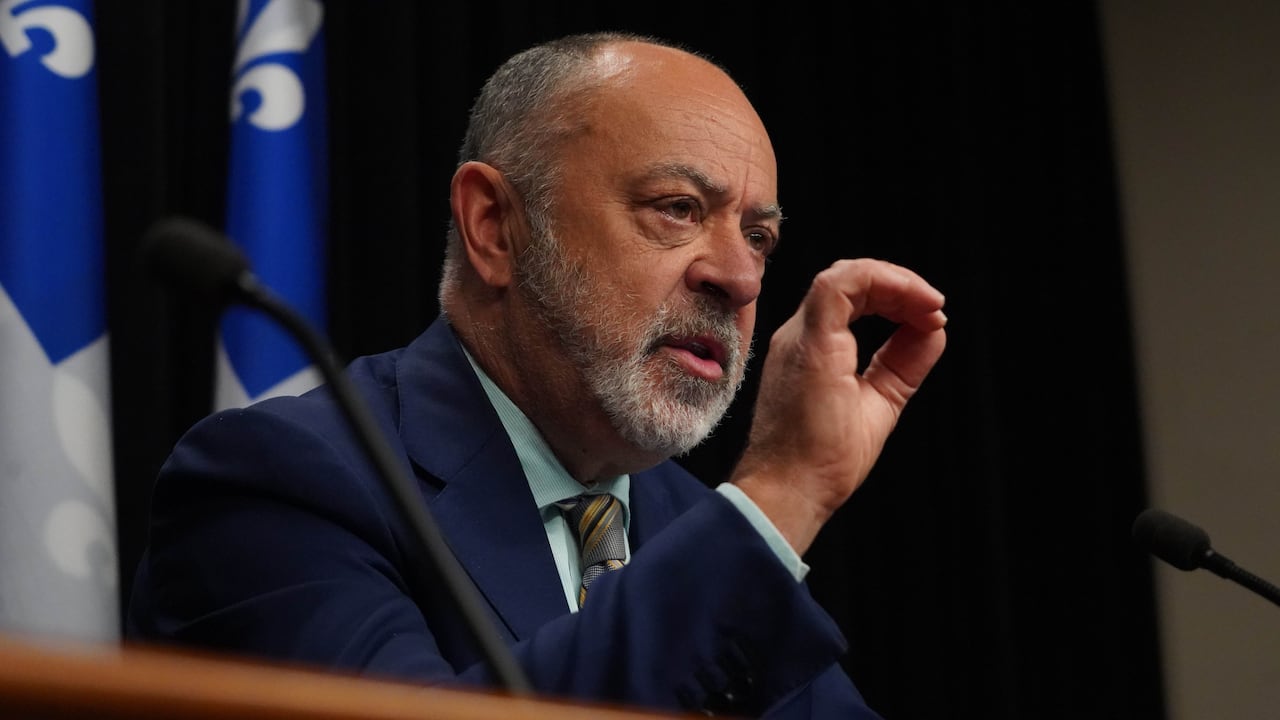

Quebec is now the first province in Canada to publicly cover part of the cost of a new HIV prevention drug experts call a much-needed intervention. Apretude is a long-acting injectable drug that could replace daily oral pills.

Global efforts at ending the HIV pandemic by 2030 have stalled. There still are more than 30,000 new infections in the U.S. each year and about 1.3 million worldwide.

Only about 400,000 Americans already use some form of PrEP, a fraction of those estimated to benefit. A recent study found states with high use of PrEP saw a decrease in HIV infections, while rates continued rising elsewhere.

Trial participant says he forgets he’s on PrEP

About half of new infections are in women, who often need protection they can use without a partner’s knowledge or consent.

One rigorous study in South Africa and Uganda compared more than 5,300 sexually active young women and teen girls given twice-yearly lenacapavir or the daily pills. There were no HIV infections in those receiving the shot, while about two per cent in the comparison group caught HIV from infected sex partners.

A second study found the twice-yearly shot nearly as effective in gay men and gender-non-conforming people in the U.S. and in several other countries hard-hit by HIV.

Ian Haddock, who lives in Houston, had tried PrEP off and on since 2015. But he jumped at the chance to participate in the lenacapavir study and continues with the twice-yearly shots as part of the research followup.

“Now I forget that I’m on PrEP because I don’t have to carry around a pill bottle,” said Haddock, who leads the Normal Anomaly Initiative, a non-profit serving Black 2SLGBTQ+ communities.

“Men, women, gay, straight — it really just kind of expands the opportunity for prevention,” he said.

Just remembering a clinic visit every six months “is a powerful tool versus constantly having to talk about, like, condoms, constantly making sure you’re taking your pill every day,” Haddock added.

“Everyone in every country who’s at risk of HIV needs access to PrEP,” said Dr. Gordon Crofoot, who helped lead the study in men. “We need to get easier access to PrEP that’s highly effective, like this is.”

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.