Former prime minister Justin Trudeau upended 150 years of Canadian parliamentary tradition when he dumped Liberal senators, named Independents to the upper house and generally stripped the place of partisan elements.

The experiment produced mixed reviews, with some old-guard senators — those who were there well before Trudeau — arguing the Senate is now irrelevant, slower, less organized and more expensive.

Some of Trudeau’s appointees say the reforms have helped the Red Chamber turn the page on the near-death experience of the expenses scandal, which they maintain was fuelled by the worst partisan impulses. Defenders of the new regime say partisans are pining for a model that’s best left in the dustbin of history.

The Senate has been more active in amending government bills and those changes are not motivated by party politics or electoral fortunes — they’re about the country’s best interest, reformers say.

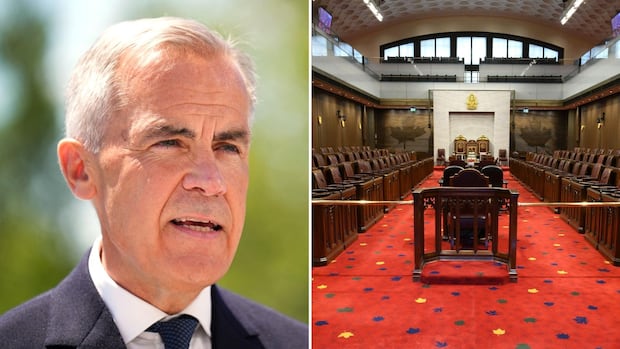

As the debate rages internally over whether the last 10 years of change have been worth it, Prime Minister Mark Carney has said almost nothing about his vision for the upper house.

The HouseIs Trudeau’s reformed Senate working? Here’s what senators say

This week on The House: Six senators discuss whether Justin Trudeau’s Red Chamber overhaul is working. Carleton professor Jonathan Malloy weighs in on Senate representation and Government House Leader Steven MacKinnon explains the new federal government’s strategy in dealing with the Senate.

Under the current model, would-be senators are recommended by an outside panel but the decision is still up to the prime minister.

Most of Trudeau’s early picks were strictly non-partisan but, as polls showed his party was headed for an almost certain defeat, he increasingly named Liberals to the chamber.

Carney has already scrapped Trudeau’s carbon tax, introduced legislation to bypass Trudeau-era regulations, repaired once-frosty relations with the provinces and taken a different approach to the trade war. All that has some senators wondering whether the non-partisan push in the Red Chamber will be the next domino to fall.

In an interview with CBC Radio’s The House, House leader Steve MacKinnon signalled there may indeed be more changes coming.

“I think the Senate is very much a work in progress,” he said.

“We continue to work constructively with the Senate in its current configuration and as it may evolve. I know many senators, the various groups in the Senate and others continue to offer some constructive thoughts on that.”

Asked if Carney will appoint Liberals, MacKinnon said the prime minister will name senators who are “attuned to the vagaries of public opinion, attuned to the wishes of Canadians and attuned to the agenda of the government as is reflected in the election results.”

Carney is interested in senators who “are broadly understanding of what the government’s trying to achieve,” MacKinnon said.

As to whether he’s heard about efforts to revive a Senate Liberal caucus, MacKinnon said: “I haven’t been part of any of those discussions.”

Alberta Sen. Paula Simons is a member of the Independent Senators Group, the largest in the chamber and one mostly composed of Trudeau appointees (she is one of them, appointed in 2018).

Simons said she knows the Conservatives would scrap Trudeau’s reforms at the first opportunity. What concerns her more are those Liberals who are also against the changes.

“There’s a fair bit of rumbling about standing up a Liberal caucus again. And I am unalterably opposed to that,” she said.

When the last Liberal caucus was disbanded, some of its members regrouped as the Progressive Senate Group, which now includes senators who were never Liberals.

“To unscramble that omelette, whether you’re a Liberal or a Conservative, I think would be a betrayal of everything that we’ve accomplished over the last decade,” Simons said.

“I think the Senate’s reputation has improved greatly as a result of these changes. I think the way we are able to improve legislation has also increased tenfold. It would be foolish and wasteful to reverse that.”

Still, she said there’s been pushback from some Trudeau appointees.

Senate debates are now longer, committee hearings feature more witnesses and there’s more amendments to legislation than ever before, she said.

Not to mention Independent senators can’t be whipped to vote a certain way. All of that makes the legislative process more difficult to navigate.

“Partisan Liberals don’t like the new independent Senate because they can’t control it as easily,” she said.

Marc Gold, Trudeau’s last government representative in the Senate who briefly served under Carney before retiring, said his advice to the new prime minister is to keep the Senate the way it is.

“The evolution of the Senate to a less partisan, complementary institution is a good thing. I think it’s a success, and I certainly hope that it continues,” Gold said.

On the other side of the divide, Quebec Sen. Leo Housakos, the leader of the Conservative Senate caucus, welcomes the idea of injecting some partisanship.

He said, under the current model, the chamber is less influential.

“The place has become, unfortunately, an echo chamber,” he said.

Housakos said the old Senate was more honest, when members were more transparent about their political leanings.

Many of Trudeau’s Independent appointees are Liberal-minded and their voting record suggests they often align with the government, Housakos said.

“Look at how often they’ve held the government to account,” he said. “Look how often they’ve asked the difficult questions in the moments when the government needed … their feet held to the fire.”

Simons sees things differently.

“It’s really difficult for people who’ve been brought up in a partisan milieu, whether they’re Conservative or Liberal or New Democrat, to understand that it is actually possible to be a political actor without a team flag,” she said.

“It’s not my job to stand for a political party.”

Saskatchewan Sen. Pamela Wallin is a member of the Canadian Senators Group, which is made up of non-partisan senators including some who, like her, formerly sat as Conservatives.

She said the current process has produced some senators who are political neophytes, unfamiliar with the Senate’s traditional role.

“I don’t care if somebody belongs to a political party.… I think people need to be better educated about what they’re signing up for,” she said.

“Our job is to be an arbiter of legislation and laws put forward by the House of Commons. It’s not a place where we can all ride our individual hobby horses.”

That’s a reference to the proliferation of Senate public bills — legislation introduced by senators themselves.

These bills often have no hope of passing through both chambers, while still taking time and resources to sort through.

There is data to support Wallin’s contention that there are more of these bills than there were before the Trudeau reforms.

During Stephen Harper’s last term, there were 56 Senate public bills introduced and nine of them were passed into law, according to a CBC News review of parliamentary data.

By comparison, Trudeau’s final session saw 92 bills introduced over a shorter time period. Only 12 of them passed — a worse success rate.

In the first few weeks of this new Parliament, more than 32 such bills have already been introduced, some of them a revival of those that died on the order paper.

Wallin said those bills often reflect senators’ “personal interests or the interests that they’ve shared over a lifetime.”

She wants the Senate to take a “back to basics” approach.

“Our job is sober second thought,” she said.

Wallin is also calling for better regional representation in the Senate, which may be a tricky proposition given the constitutional realities. A change in seat allocation would require cracking open that foundational document, a politically unpalatable idea.

Still, Alberta separatists are agitating for change, calling the current breakdown grossly unfair.

Housakos said depriving some parts of the country of meaningful representation needs to be addressed.

In B.C., for example, the province’s nearly six million people are represented by just six senators.

P.E.I., by comparison, has four senators for about 180,000 people — an allocation formula that dates back to Confederation.

“Western Canada has a legitimate beef. They are not fairly represented in the upper chamber,” Housakos said. “It’s probably the biggest problem that needs to be addressed.”

But the government isn’t interested in that sort of change, MacKinnon said.

“I see no space on the public agenda for constitutional discussions,” he said.