Businesses on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border are struggling. And it’s not just tariffs. It’s the vast new compliance requirements they have to meet, and the bureaucracy which is just as confused as the businesses. That’s costing time and money when businesses can ill afford to lose either.

The central plank of the federal government’s position is that Canada has secured sweeping exemptions to the U.S. tariffs for the vast majority of products.

“Canada currently has the best deal of any of the United States’ trading partners in the world — 85 per cent of our trade with the United States has no tariffs,” said Prime Minister Mark Carney this week, adding that Canada has the lowest tariff rate of any country in the world.

Don’t tell that to Patrick Fulop. He went through the process of becoming compliant with the Canada-U.S.-Mexico-Agreement (CUSMA), the trade deal that replaced NAFTA in 2020.

Fulop’s company, Quebec-based Grappling Smarty, sells what he calls a grappling dummy. It’s like a human-shaped punching bag, but built specifically so MMA fighters can practise grappling and wrestling moves. Seventy-five per cent of his sales go to U.S. customers.

The shock of the tariffs was bad enough. To make matters worse, how they’ve been applied has been wildly arbitrary.

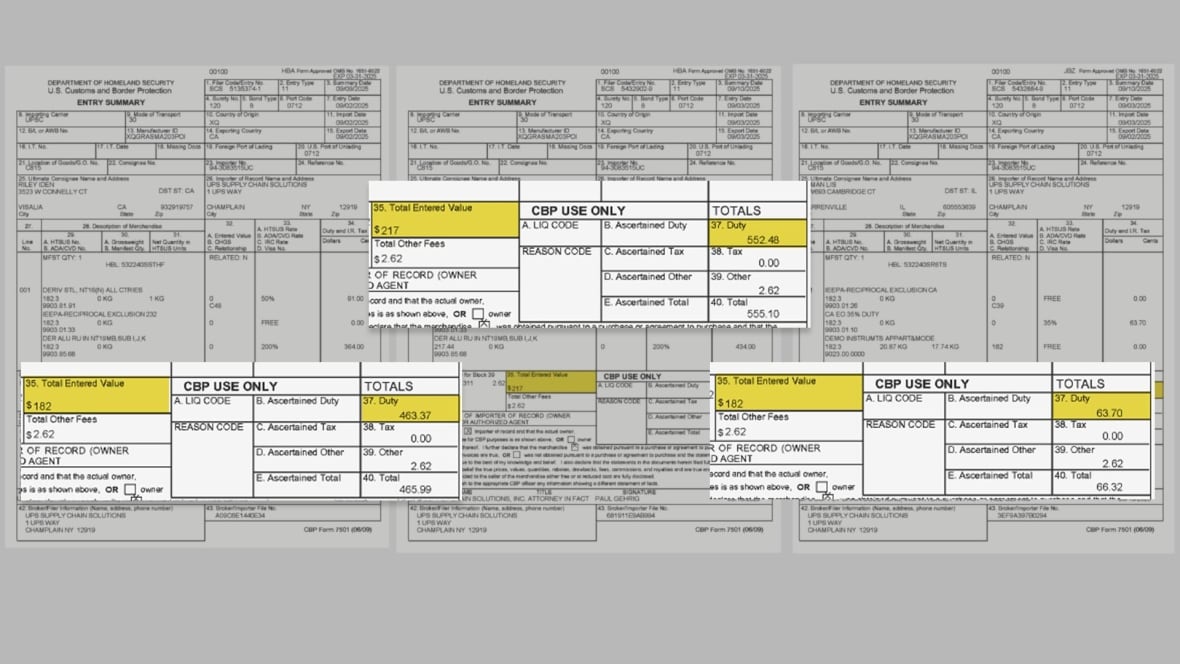

Fulop shared dozens of invoices with the CBC News showing how much U.S. Customs and Border Protection was claiming he owed on shipments. Page after page showed different calculations using different tariff codes. One invoice charged $66 citing one set of tariffs. Another charged $555 using a different set of tariffs. Both were for the exact same $250 product.

“We are talking 100 to 200 per cent. I think on average it’s 150 per cent we have been paying on those orders. It makes absolutely no sense. There’s no way that Canadian businesses can continue to serve the American customer in this environment,” he said.

Fulop ships his products through UPS which also acts as broker and charges the import duties. UPS said in an email that it was “actively working” to resolve his concerns.

But on its website, UPS says duties will be assessed based on effective tariff rates or specific duties depending on country of origin.

That has left a lot of room for interpretation and confusion about what rate should be applied to which products. And it’s precisely the sort of thing trade experts have been warning about.

‘Layer upon layer’ of bureaucracy

Scott Lincicome, the vice-president at the Cato Institute in Washington, says businesses, brokers and shippers all have no idea how to process the proper rates.

“You’ve really gone from almost overnight, a pretty simple system to one that has layer upon layer upon layer of bureaucracy, and it’s so complicated and it’s changing constantly,” he said.

Lincicome says it used to be quite clear what tariffs were applied in specific cases. There were court cases and volumes of trade documents that laid out in painstaking clarity how the system worked. Since U.S. President Donald Trump started imposing tariffs last winter, he says companies have had to sift through various types of tariffs imposed at different rates for different countries and different products.

“Now, it’s a lot more complicated because the product might have not just a reciprocal tariff rate, but a Section 232 rate. There’s a country rate, I mean, there’s now 100 different country rates,” he said.

And in some cases, those tariffs are meant to be stacked, that is, added on top of each other.

The shipping companies that accept the product in the U.S. are ultimately responsible for making sure the right tariff is paid. So some experts say those companies are simply charging the maximum rate and letting the exporter sort out whether they should get a refund.

Trade lawyer Mark Warner has warned about that. He’s also questioned whether every company that claims it has been CUSMA-certified actually meets the criteria. Warner says there are stiff penalties for everyone involved in shipping products that aren’t actually compliant.

“With criminal penalties for fraudulent compliance, I don’t think the logistics firms want to assume any of the risk,” said Warner, principal with the Toronto firm MAAW Law.

Whatever the reason, the result is yet more uncertainty. And that is just another barrier to trade.

Back at Smarty Grappling, Fulop is scrambling to find a solution. He’s covering the tariff costs for existing orders, but doubled his price to cover future orders. Meantime, he’s bolstering his domestic marketing and trying to find new customers in other markets.

But he’s mostly frustrated that the CUSMA compliance he worked so hard to secure doesn’t seem to be worth very much right now.

“We thought we were getting a good deal because CUSMA … was supposed to keep on being respected, and that’s not the case,” he said.