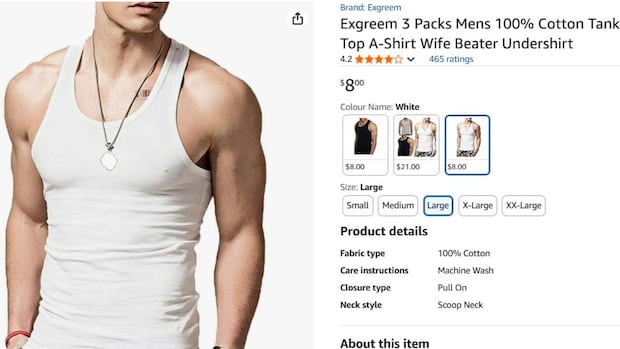

Several ads for men’s tank tops remain on Amazon’s Canadian website, despite an Ad Standards Council ruling that the phrase used to describe them — “wife beater” — is offensive, trivializes domestic violence and violates Canada’s advertising code.

The slang term refers to a certain style of tight-fitting tank tops introduced in the 1930s as a men’s undershirt. The shirt entered into popular culture in 1951, when Marlon Brando wore one while playing the hard-edged, violent Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire.

Amazon’s continued acceptance of the slang term and Canada’s inability to force the retailer to remove it have angered some women’s rights advocates.

“We should be aiming to live in a culture that respects women,” said Harmy Mendoza, executive director of WomanACT, an advocacy group that works to end intimate partner violence. “Wife beater is a term that offends, [and] insults not only women but survivors.”

After viewing the Amazon ads posted by third-party sellers, Mendoza started a petition this week to lobby the online retail giant to remove the phrase from its website.

“It normalizes gender-based violence and we want to live in a society that targets and eliminates that type of behaviour,” she said.

In 2024, a seven-member council with Ad Standards Canada, the industry’s self-regulatory body, reached a similar conclusion regarding a complaint about an Amazon ad for a men’s “wife beater” tank top. The council ruled the ad violated the Canadian Code of Advertising Standards by showing “indifference to the unlawful behaviour of violence against women.”

The council asked Amazon to remove or amend the ad. However, adherence is voluntary, and it appears that the U.S.-based company has chosen to ignore the council’s request.

In response to the initial complaint, Ad Standards reported that Amazon defended the phrase, stating that “this clothing descriptor was commonly understood and accepted across retail and popular culture.”

Amazon also said the phrase didn’t breach its Offensive Products Policy, because it referenced a type of clothing, and wasn’t an “endorsement of harmful behaviour,” reported Ad Standards.

CBC News found 10 ads for “wife beater” tops sold by third parties on Amazon, and sent them to the company, along with concerns Mendoza raised about the phrase.

Amazon responded in an email that the company strives “to maintain a store that is welcoming for all,” and that it exercises judgment and keeps “cultural differences and sensitivities … in mind” when making decisions about product listings on its website.

CBC News also contacted each of the dealers selling “wife beater” tops on Amazon. So far, just one, WANGYUNHUI2025, responded by removing the term from its ads.

“I deeply regret that it has caused harm,” said the dealer. “I apologize for the oversight and appreciate your bringing this matter to my attention.”

Why is the code voluntary?

The Canadian Code of Advertising Standards is a voluntary code of conduct developed and administered by the industry funded Ad Standards.

The non-profit organization declined to do an on-the-record interview with CBC News, or provide more details about the Amazon case. It did, however, provide background information.

Ad Standards says the code is voluntary because it was developed by the industry to complement Canada’s advertising laws. The organization noted the vast majority of companies comply with the rules.

Amazon is facing criticism for selling children’s clothes on its site with a sexually explicit message. The products are banned under Amazon’s “offensive products” policies, but the company only removed them after a CBC News investigation.

Activists call for regulatory body

As for Amazon, Ad Standards pointed out the retailer has faced repercussions, as it was publicly named in the council decision posted online.

But that’s not good enough for some activists. Sociologist Kaitlynn Mendes says the federal government needs to establish a regulatory body that can ensure online platforms remove content that’s deemed harmful.

“We need to have these mechanisms to force them to make these changes,” said Mendes, Canada Research Chair in Inequality and Gender, and a professor at Western University in London, Ont.

“Something that actually has teeth that will make these corporations comply, I think, is incredibly important and it maybe has never been more important in this day and age.”

In 2023, Canadian police received 139,020 reports of intimate partner violence. Most of the victims were women.

In 2025, several regions, such as parts of Ontario and Nova Scotia, have reported that domestic abuse cases are on the rise.

What happened to the Online Harms Act?

Some countries have enacted legislation to prevent online content considered harmful.

Under the European Union’s Digital Services Act, online platforms, including e-commerce sites like Amazon, face strict rules for user safety and content moderation.

The U.S. Trump administration has criticized the act, claiming it’s costly for American tech companies and limits free speech. Meanwhile, Amazon is taking the EU to court, arguing it should be exempt from the legislation, because its online marketplace doesn’t pose the systemic risks addressed in the act.

Last year, Ottawa introduced Bill C-63, the Online Harms Act, designed to police harmful content online. The legislation, which largely targeted social media platforms, proved controversial due to concerns it could stifle free speech.

Both the controversy and the bill died in January 2025 when Parliament was prorogued.

CBC News asked the federal government if it had any plans to revive its Online Harms Act, and if so, what it may include.

Heritage Canada responded in an email, saying the government is committed to delivering on the promises made in the Liberal Party’s platform, unveiled during the last federal election.

The 65-page document does not appear to contain proposals for legislation that would force companies to adhere to Canada’s advertising code.

But that hasn’t deterred advocates like WomanACT’s Mendoza, who hopes her online petition for Amazon to eliminate the term “wife beater” from its website gains traction.

“It’s important that we don’t use … that type of language in Canada,” she said. “Please remove it.”