Education Minister Demetrios Nicolaides says the Alberta government won’t spend beyond $2.6 billion over four years in new spending to resolve a contract dispute with striking teachers.

“The $2.6 billion is what we have available,” Nicolaides said in a Wednesday interview.

“We’re happy to work within that bucket to provide teachers with an increase [in wages] and help address some of the increasing complexity issues that we see in our classroom. But we do have a limited bucket that we’re operating with.”

Last month, nearly 90 per cent of Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA) members voted down a contract that would cost the province’s treasury an additional $2.6 billion between 2024 and 2028.

The rejected offer included a 12 per cent general wage increase, plus an amalgamation of salary grids in 2026 that would give some teachers wage increases of up to five per cent.

The offer included a government promise to pay the cost of adding 3,000 more teaching positions and 1,500 more educational assistants to schools.

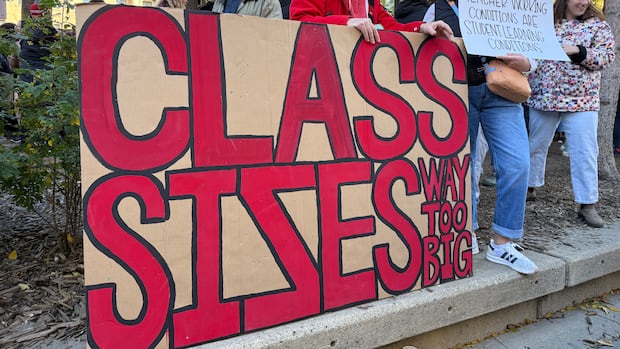

The impasse led 51,000 teachers to walk off the job Monday.

Classes are cancelled at around 2,000 public, Catholic and francophone schools across the province.

The Teachers’ Employer Bargaining Association, which negotiates with the ATA on behalf of the government and school boards, is locking teachers out as of Thursday afternoon.

On Tuesday, Nicolaides told CBC radio’s The Calgary Eyeopener that the provincial government was open to hearing how many teachers the ATA thinks would be adequate to improve classroom conditions.

In a Wednesday interview, he clarified that funding more than the promised 3,000 teaching positions would come at the expense of other parts of the offer.

“There would have to be trade-offs,” he said. “We’re really eager to see the ATA come back to the table and bring forward a proposal.”

Teachers have twice voted down the general salary offer of 12 per cent increases over four years, saying it doesn’t catch their wages up with inflation, nor account for their additional workloads.

ATA president Jason Schilling has said Alberta would need at least 5,000 more teachers to meet the recommended class-size average guidelines in a 2003 Alberta Commission on Learning (ACOL) report — one major outcome of a 2002 teachers’ strike.

The ACOL report says research at the time showed smaller class sizes made the most difference to children in the youngest grades and socioeconomically disadvantaged students.

The ACOL report recommended Alberta school divisions aim to have, on average, Kindergarten to Grade 3 classes have 17 students, Grade 4-6 classes have 23 students, junior high classes have 25 students and high school classes have 27 students.

Alberta’s government cancelled class size reporting in 2019. Data from Edmonton Public Schools, which still tracks it, and anecdotes from teachers, students and parents suggest class sizes in many schools are much larger than those recommendations.

Although Nicolaides said he believes class size matters, he thinks class-size caps are “arbitrary” and don’t improve students’ academic performance.

He did not directly answer a question about whether the government is interested in achieving those recommended class sizes.

“Having a class size cap of 22 versus 29 has no impact on that student’s academic performance,” he said.

“What’s most important is that we build more schools, we hire more teachers, we get more EAs into the classroom and help address the conditions that we’re seeing.”

In a statement, the ATA said it was concerning to hear the minister call class-size caps “arbitrary.”

The statement said provincial policy has long recognized that “reasonable” student-teacher ratios are central to student success, especially in the early grades, and the principle is evidence-based.

“When class sizes continue to balloon, teachers have less time to understand each learner, personalize instruction and build the trust that fuels growth and confidence,” the ATA’s statement reads. “These human factors, far more than simple test scores, define educational quality.”

The ATA said hiring more teachers is a temporary solution to large and complex classes.

“Formally establishing teacher-student ratios will ensure Alberta classrooms are permanently protected from financial neglect, making quality learning conditions a non-negotiable standard into the future,” the statement reads.

Last week, Premier Danielle Smith said her government was unwilling to consider class-size caps because the province doesn’t have adequate school space.

NDP education critic Amanda Chapman said on Wednesday the minister’s comments are out of touch with reality.

“We’re not really talking at this point about whether we have 22 or 29 kids in a classroom,” she said.

“We’re talking about whether we have 22 or 40 kids in a classroom, because those are the classroom sizes that we’re hearing about that are causing concerns.”

Chapman said education policymakers must also look at the student’s school experience, not just their report cards.

She pointed to a high school science class so full, students were assigned in labs to work in groups of four instead of pairs.

UCP underfunded schools for years: Opposition

Chapman said it is unreasonable to put a cap on the amount of funding required to improve the education system, and it shouldn’t be the ATA’s responsibility to negotiate adequate school staffing as part of their employment contracts.

She said it was the government’s decision to keep increases to Kindergarten-to-Grade 12 education funding lower than enrolment growth and inflation rates, and that has led to inadequate staff to meet students’ diverse needs.

Chapman said it would still make a difference for students if schools had more funding to hire extra teachers, educational assistants, psychologists, mental health therapists and other professionals.

“If you talk to teachers, complexity in the classroom is absolutely their number one issue right now,” Chapman said, referring to growing numbers of students with disabilities, behavioural or mental health challenges, medical needs or English language learners.

Teachers in several other provinces, including B.C., Ontario and Quebec, have class-size caps or limits on the number of students in each class with complex needs. The caps are either in legislation or written into teachers’ contracts.

University of Alberta education policy studies professor Darryl Hunter said Wednesday that other jurisdictions adopted those policies after legal action or advocacy from teachers who wanted to make working conditions in schools more manageable.

He said class size is one of many factors that can affect a student’s classroom experience. He said a reasonable class size depends on the age of the students, the composition of the class, what subject they’re studying and whether there are any safety concerns.

“I wouldn’t want 42 students in a chemistry class,” Hunter said. “Something would get blown up.”

Caps tend to increase the amount of bureaucracy for schools, which may not serve students well, he said.

However, Hunter said academic achievement isn’t the sole goal of public education. He said students also need to be in environments where they can communicate and work together.