The crew of Artemis II is set to blast off from Cape Canaveral, Fla., as early as February and head toward the moon, where they will swing around it and head home. It’s the first step in getting boots on the moon for the first time in more than 50 years.

This isn’t just about planting a flag and collecting some rocks, as it was during the space race in the 1960s. NASA’s ambitious Artemis program has the long-term goal of exploring the moon, with a continuous human presence. And from there, on to Mars.

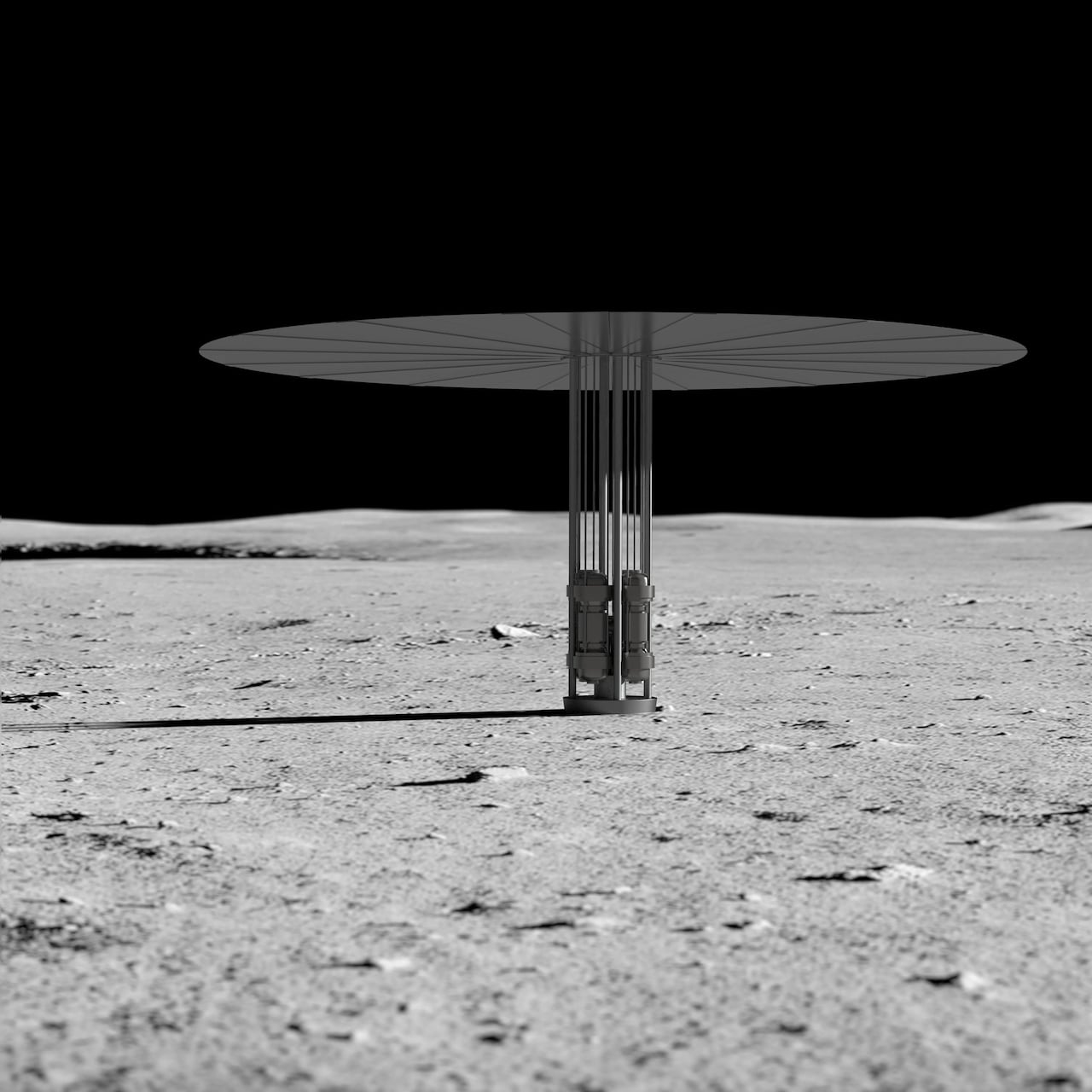

In order to maintain a presence on the moon, there’s going to be a need for energy. So how do you maintain a colony of people in a place that has roughly 14 days of sunlight followed by 14 days of darkness?

The answer: nuclear energy. And Canada is looking to step up.

Earlier this month, the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), awarded $1 million in funding to the Canadian Space Mining Corporation (CSMC) to develop a low-enriched uranium nuclear reactor to be used on the moon.

When we think about nuclear reactors, we typically think of large buildings or steam towers the likes of which are seen on The Simpsons.

But there are also small modular reactors that are assembled in a factory and transported to a location.

And then there are micro modular reactors, the likes of which CSMC is looking to build, which are far smaller.

How far-fetched is the idea of nuclear reactors on the moon?

“The idea of using nuclear in space more generally is not actually a new one. So if we go back to the Cold War, the Russians were up to things with nuclear reactors in space,” said Kirk Atkinson, associate industrial research chair in the department of energy and nuclear engineering at Ontario Tech University in Oshawa.

“NASA has been working on it for a decade or more now, and they’ve done demonstration experiments in the U.S. where they make a little reactor and it behaves the way that you expect it to behave.”

Canada in unique position

Canada isn’t the only country vying to build a nuclear reactor that can be used on the moon.

In August, NASA announced that it seeks to put a nuclear reactor on the moon by 2030, five years earlier than China’s and Russia’s plans for their joint reactor.

So why is Canada aiming for a reactor on the moon when it doesn’t even have the capability to launch a rocket from its home soil (yet).

“The international community is working together to establish a permanent presence on the moon,” said Daniel Sax, founder and CEO of the Canadian Space Mining Corporation. “Jeremy Hansen is going up on the next flight to the moon, and Canada is looking to contribute things to the international effort as it has contributed things in the past.”

Canada has a long if somewhat muted history of contributions to space exploration, with the Canadarms and tech that has flown to distant asteroids and Mars.

MDA Space, which built the Canadarms, was also recently awarded $500,000 from the CSA for the “development of algorithms and autonomous plant management tools for a nuclear power system on the lunar surface.”

“Canada is really good at space technology. We’re also really good at nuclear,” Sax said. “So we’ve been working on this, looking to leverage both those skills.”

Sax says this type of reactor isn’t limited to the moon. The company plans to use similar technology for use in remote and Indigenous communities, many of which are still using diesel.

Lunar challenges

For the moon reactor, it would be built here on Earth and then sent to the moon Sax explained. It would run partly autonomously and partly under supervision here on Earth.

But Atkinson said that building a reactor to operate on the moon — which doesn’t have an atmosphere, where water would freeze and where there’s low-gravity — will have its challenges. You can’t use water or even air to cool the reactor.

Then there’s the issue of what to do with the spent fuel.

“We’ll have to think about nuclear waste disposal. I suspect probably that’s one of the last things they’ll think about,” said Jamie Noel, a chemistry professor at Western University in London, Ont. “[But] It should start with the design of the reactor.”

There’s also the regulatory side of it.

Canadian Space Agency astronaut Jeremy Hansen is headed to the moon on the Artemis II mission. He sits down with CBC’s Nicole Mortillaro to talk about the physical, mental and collaborative part of training to go to the farthest place humanity has ever gone.

“Legal questions aside, who is actually the regulator of something on the moon? In Canada, it’s the … Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission,” Noel said. “The [Atomic Energy of Canada] tried this idea of an autonomous reactor. Like once a month, they’d send a technician up there to check on things. And the CNSC said absolutely not.”

Whether or not that will be the case for the moon remains to be seen.

Sax, whose company is also researching ways to get water from the moon, is excited for the future of human exploration, and says he is hopeful that the company’s micro modular nuclear reactors can be used in remote communities, not only in Canada, but around the world.

“I think humans will continue exploring no matter what,” he said. “And I think if we can enable that exploration, but also at the same time … bring real economic value to people’s lives here — real environmental value — and solve some of the biggest problems that we have in Canada, I think that’s something incredible to work on.”