As It Happens6:27Scientists discover dinosaur ‘mummies’ with hoofs like a horse

It’s been more than 60 million years since duck-billed dinosaurs roamed around what is now known as western North America.

Or, more accurately, since they clomped around. On their hoofs.

This, according to a new study of “dinosaur mummies” — fossils in which the external anatomies of dinosaurs are rendered in incredible detail onto thin layers of ancient clay.

It marks the first time hoofs have been found on a dinosaur or, in fact, any reptile. But the researchers behind the discovery expect more will turn up, now that people know to look for them.

“I think people’s antennae will be up now to try and make sure there’s nothing there when they’re excavating,” University of Chicago paleontologist Paul Sereno, the study’s lead author, told As It Happens host Nil Köksal.

The findings, published in the journal Science, paint the most complete picture to date of what duck-billed dinosaurs actually looked like.

What’s more, the study unravels the long-standing mystery of how these so-called dinosaur mummies formed in the first place.

The cows of the Cretaceous Period

Duck-billed dinosaurs were far more common than their more famous contemporaries of the Cretaceous Period, like the apex predator Tyrannosaurus, or horned dinosaur Triceratops.

In fact, these nearly three-metre long plant eaters were a favourite meal of the T. Rex.

Also known as Edmontosaurus — because the first fossils were discovered in southern Alberta — they roamed together in giant herds, grazing on plants, much like modern-day cows, sheep and goats.

Also like today’s grazing mammals, these dinos developed hoofs, structures that protected their toes, supported their weight, offered traction and absorbed shock from the impact of all that walking — and running for their lives.

“It’s remarkably like a later equine or horse hoof, or something that you might see on a relative, a tapir or a rhino,” Sereno said.

“There’s a shield around the outside, and then sort of a soft core on the bottom side that really resembles the mammalian hoofs that evolved so much later.”

It’s an example of a phenomenon known as convergent evolution, in which different organisms independently evolve similar features — like the wings of birds, bats and the extinct flying reptiles called pterosaurs — while adapting to similar environments or ecological niches.

What even is a dinosaur mummy?

Sereno and his colleagues identified the hoofs on a pair of detailed fossils known as dinosaur mummies. They are skeletons that, on first glance, appear to be covered in remarkably well-preserved skin.

Scientists have been uncovering these types of fossils for more than a century, many of them in the badlands of eastern Wyoming, in an area known as “the mummy zone.”

Sereno and his colleagues wanted to understand the process that creates these mummies. But the name, it turns out, is a bit of a misnomer.

“People will think of Egyptian mummies and ask what is a dinosaur mummy? That was our question in the first place,” said Sereno.

Mummification usually refers to the preservation of flesh, either intentional or natural. But these mummies, it appears, are flesh-free.

The study looks at two duck-billed dinosaur fossils excavated in Wyoming in the early 2000s.

Sereno says the specimens don’t actually contain any skin, DNA or tissue.

It’s just clay.

The two Edmontosaurus died some 66 million years ago, possibly in a drought, and their dried out carcasses were covered in a flash flood that left them coated in a film of clay about 0.025 centimetres thick.

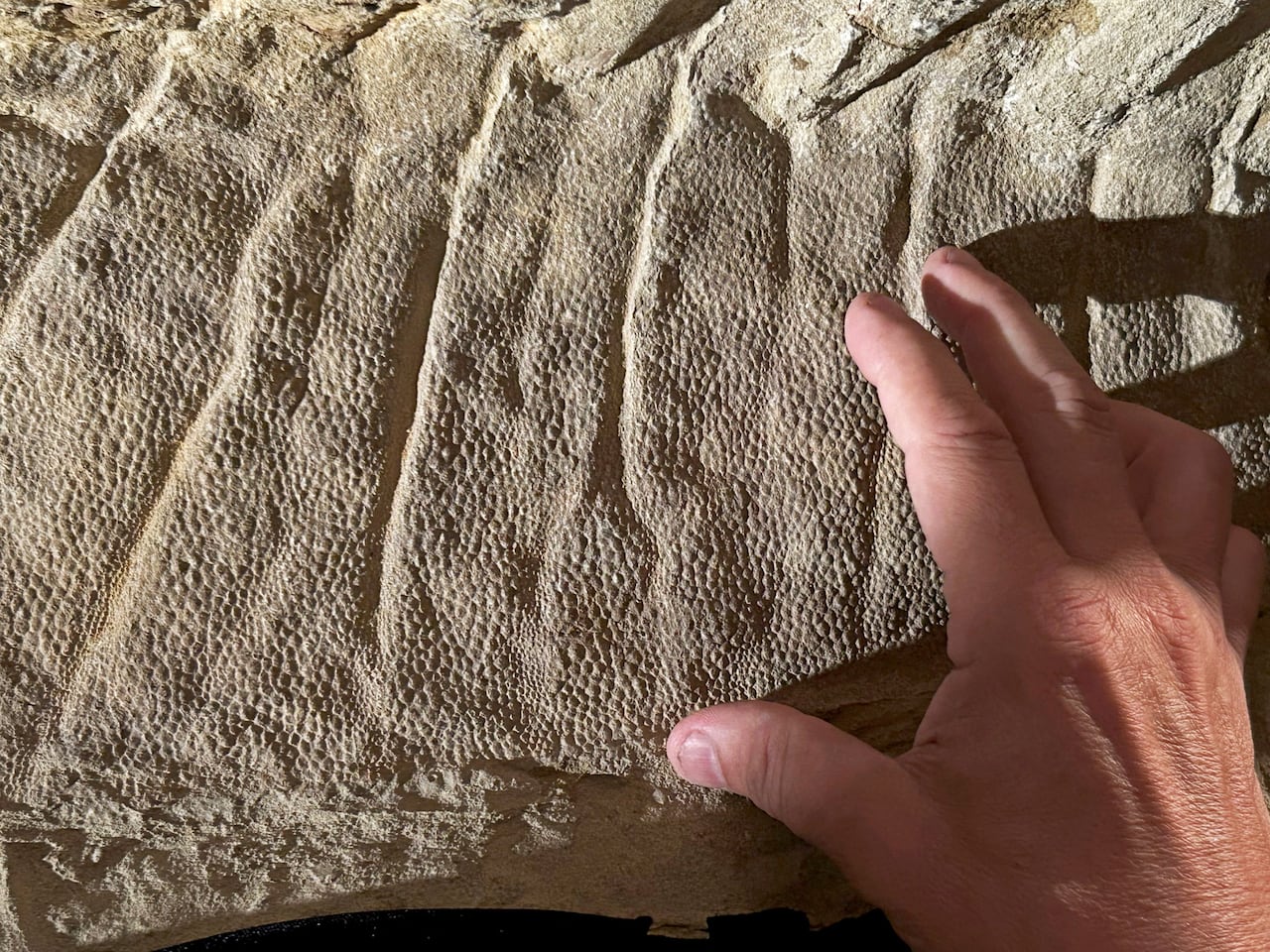

That clay then hardened with the help of microbes. When the skin and flesh decayed, it left behind bones encased in clay masks that preserved the creatures’ shapes, including the contours of their bodies and scaly skin.

“It’s a beautiful rendering of what the animal looked like,” Sereno said.

This style of mummification has preserved other organisms before, but scientists didn’t think it could happen on land. It’s possible that other mummies found at the Wyoming site could have formed in a similar way, Sereno said.

Understanding how dinosaur mummies form can help scientists uncover more of them, says Mateusz Wosik, a Misericordia University paleontologist who wasn’t involved with the discovery. It’s important to look not just for dinosaur bones, but also for skin and soft tissue impressions that could go unstudied or even get picked away during the excavation process.

More mummies offer more insights into how these creatures grew and lived, says Stephanie Drumheller, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Tennessee,

“Every single time we find one, there’s such a treasure trove of information about these animals,” said Drumheller, who wasn’t involved in the research.

These renderings, paired with what scientists already know from other fossils, paint a detailed picture of what a duck-billed dinosaur looked like, from its heads to its hoofs.

According to the study, it has a ridge running down its neck and back, which breaks out into a row of spikes running down the tail. Its skin was covered in tiny, pebble-like scales, most no bigger than those of an average lizard.

And, as we now know, it was hooved.

“This is a landmark,” Sereno said. “We really know this dinosaur now.”