For the past decade, Jamaica has been building layers of financial protection in the event of a natural disaster. Now, after Hurricane Melissa tore through the country, destroying homes, roads and essential infrastructure, the country’s strategy might pay off — and provide a model for climate-vulnerable nations elsewhere.

Last year, the country issued $150 million US in a catastrophe or “cat” bond — triggered in case of certain parameters related to how strong a hurricane is and where it passes through.

“They are linked to the central pressure of the hurricane when it makes landfall,” said Florian Steiger, CEO of Icosa Investments, a Swiss firm that focuses on catastrophe bonds. A third party needs to verify the trigger, but there’s no question in this case the necessary threshold has been crossed.

“Based on everything we’ve seen, the payouts are going to happen.”

Funds could get to Jamaica in a matter of days. The country also has multiple eggs in its disaster risk basket — including insurance policies to cover extreme rainfall and tropical storms through a regional pool that provides disaster insurance to Caribbean countries. Additionally, it can draw on lines of credit with the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank.

“Jamaica’s strategy is, in my perspective, one of the most comprehensive of any country globally at the minute,” said Conor Meenan, a risk financing adviser at the U.K.-based Centre for Disaster Protection.

In total, Jamaica’s Finance Ministry says it has about $820 million US available in financing to draw from in the days and weeks right after a disaster. That won’t cover all of the likely billions of dollars in damages needed, but the insurance-related financing will flow to Jamaica much faster and help quickly restore the most essential services like roads, health care and telecommunications.

Hurricane Melissa’s Category 5 winds tore into western Jamaica Tuesday morning, marking one of the most powerful Atlantic landfalls ever recorded. CBC’s Johanna Wagstaffe looks at how Melissa may be part of a new hurricane era: storms fuelled by record-warm seas and slowed by a shifting jet stream.

How does Jamaica’s cat bond work?

Jamaica’s $150-million US catastrophe bond was issued in 2024 with the help of the World Bank. The country funded the bond itself, while investors, mostly investment firms in North America and Europe, bought it. The bond matures in 2027, covering four hurricane seasons.

This was the second cat bond issue for Jamaica. The first round, in 2021, was funded by donors and provided the country $185 million US in case of disaster. Jamaica decided to renew that initial one last year.

If a payout isn’t triggered, the $150-million US bond behaves much like a regular one, with Jamaica paying out the full principal back to investors by Dec. 29, 2027, plus interest. And given the disaster risk, it came with an attractive interest rate of around seven per cent per annum.

And if it is, the total payout would be to the country instead of investors, depending on the severity of the hurricane. It starts at 30 per cent and continues all the way to the full bond amount. The triggers are based on a hurricane’s central air pressure and whether it passes over certain parts of the country.

That’s what sets this bond apart from other forms of insurance: Rather than being based on the amount of damage or cost of rebuilding, the insurance pays out based on the severity of the storm.

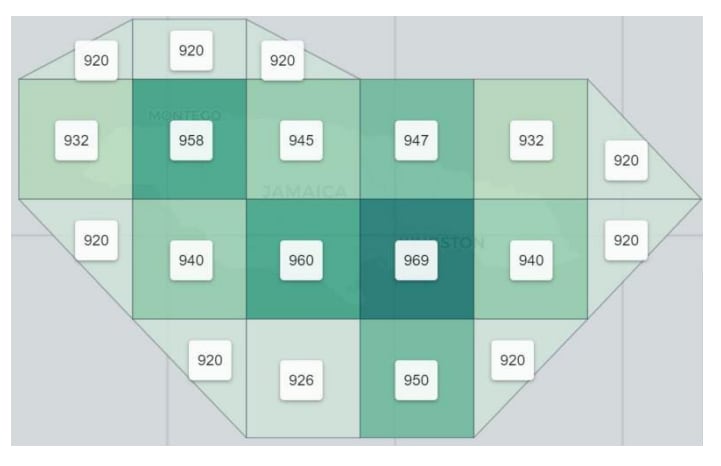

This map from the World Bank shows the air pressure limits over different parts of Jamaica for triggering the catastrophe bond:

“They divide Jamaica and some of the surrounding ocean around it into boxes,” said Steve Evans, owner and editor of Artemis, an insurance and securities-focused publication.

“Each box has a different central pressure that needs to be breached, so the storm needs to have a lower pressure than those boxes.”

The central air pressure at Hurricane Melissa’s landfall was 892 millibars (lower numbers indicate a more severe storm), indicating that the storm was severe enough to trigger a full payout of the bond.

Disastrous investments

Losing $150 million US might seem like a major hit for investors, but the impact on the entire market would not be too significant.

“We’re talking about one transaction with a nation of $150 million US. For a market that’s more than $50 billion US,” Steiger said.

Most catastrophe bonds are issued in richer countries, especially the U.S., he said. Analysts argue that the large bond market offers an opportunity for lower-income countries to spread their climate risk.

In fact, they say the market has an appetite for much more investment in catastrophe bonds for developing countries.

“They do see them as doing a social good. The investors I speak with are very focused on, still very focused, topics like ESG,” Evans said, referring to investing standards related to enhancing environmental, social and governance performance.

Jamaica’s strategy, the analysts said, could be a model for the rest of the region and other climate-vulnerable countries to access money quickly after a disaster.

They will be watching closely as the country draws on its various insurance and financing mechanisms in the coming days — an example of what governments can do to prepare for more severe storms like Melissa, increasingly being fuelled by climate change.

“Cat bonds are not the answer, but they can be a part of the answer,” Steigler said.

“I would hope that a lot of people see this as an example of something that can be assisting in broadening out the resilience of economies around the globe, and also bringing people together to better share the risk around the globe.”