White Coat Black Art26:30Diabetes care on wheels

Reaching into his kitchen cupboard, Jeremy Auger pulls out the Fruit Roll-Ups, Pop Tarts, potatoes, and oatmeal he received in the food hamper from a church.

“It’s all high in carbs,” he told Dr. Brian Goldman, host of CBC’s White Coat, Black Art, in his Calgary apartment.

The amount of carbs matters, because as someone with late-onset Type 1 diabetes, he needs to closely watch his carbohydrate intake.

Until recently, the 34-year-old says his blood sugar levels were “all over the place.”

That’s why he visits endocrinologist Dr. David Campbell and other staff at the diabetes mobile clinic.

The bus, as it’s often called, brings care directly to places like The Alex Community Health Centre, where those who are homeless or who have lower incomes may visit.

When diabetics are without housing, they’re less likely to get the “high-quality care they need,” says Campbell, an associate professor at the University of Calgary’s Cumming School of Medicine.

Without that care, complications from diabetes could result in amputations, kidney failure, heart disease, and strokes.

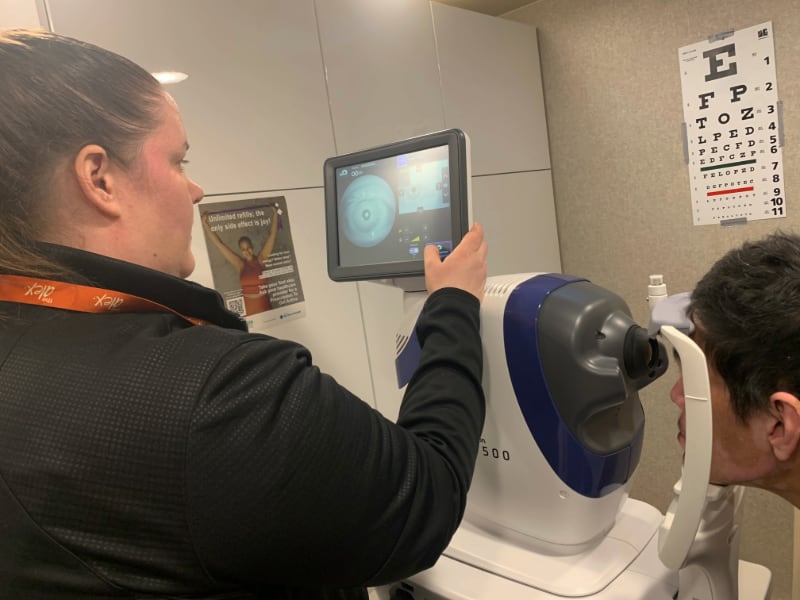

Health-care staff on the bus can do foot care, plus tests like retinal scans, blood and urine screening with results delivered in minutes.

Other staff help people with their diets or connect them to programs for housing or counselling.

“We’re a one-stop-shop,” said Erin Dartnell, the mobile clinic’s registered nurse.

Diabetes is one of the most common chronic diseases in Canada. Roughly 10 per cent of Canadians live with diagnosed Type 1 or 2 diabetes, with that percentage expected to rise within nine years, according to Diabetes Canada.

Research done by Campbell and others shows there is a higher risk of death and diabetes-related health issues for those experiencing homelessness when compared to those who have stable housing and regular access to preventative health care.

“With all diabetes care, it’s [about] trying to be more proactive about it,” said Campbell.

Dr. Kaberi Dasgupta, a physician, researcher, and professor of medicine at Montreal’s McGill University, says there is an “enormous gap” in diabetes care for those with unstable or no housing.

How it works

Every Wednesday, the four staff members working on the diabetes bus that day could see on average five to 10 patients.

Some have appointments, others are walk-ins.

“The whole point of the mobile program is meeting clients where they’re at just because of the barriers they may face,” said Lindsay Huard, whose job is to help patients access community programs.

That’s a change for patients like Auger. When he was living on the streets five years ago, he would get what Campbell calls episodic care from endocrinologists.

“He’d see them once or twice and then fall off the radar and be discharged from their caseload because he missed an appointment and needed a new referral,” Campbell explains, adding the wait time for an endocrinologist can be six to 12 months.

Since visiting the diabetes mobile clinic, Auger says his blood sugar levels are stabilized thanks to a change to his insulin medication and learning how to improve his diet.

Auger doesn’t have to worry now about paying for transit to get to multiple appointments. He can get most of the care he needs through the mobile clinic.

“It’s pretty awesome. It’s just easier than going all the way down to where we usually go to get the care we need,” he said.

Campbell says in addition to hearing from patients like Auger, they’re also conducting a study to determine whether the diabetes bus is improving people’s health.

Pilot project status

The idea of a mobile clinic is not new. Other areas of health care use travelling clinics for breast cancer screening to mental health and addictions care.

The mobile diabetes clinic in Calgary is in the second year of a two-year pilot project funded through grants and donations. Campbell says recently secured funding will extend the pilot for another 18-24 months after July 2026.

His dream is for the mobile clinic to become a regular part of the health-care system.

But Dasgupta says that can be a challenge in this country.

Some have said Canada is “a country of perpetual pilot projects.”

Dasgupta, who is currently doing research into how to create and scale up diabetes prevention programs in Canada, says that doesn’t need to be the case.

“We can’t let those pilot projects be kind of like a dead end road. You show something works, a little bit of a celebration and then nobody acts on it. That is part of the problem,” she said.