There are really just about two solid foods that eight-year-old Mohammad Farhad will reliably eat: boiled eggs, because of the taste, and spaghetti or lasagna because of the shape.

Mohammad, mom Ramzia El Annan explains, has avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, known as ARFID.

While it’s an eating disorder, it differs from anorexia or bulimia because it isn’t driven by concerns about weight or body image. Instead, it’s a severe, sometimes debilitating, sensory reaction to many or most types of food.

El Annan says she wants to share her family’s story because the disorder is often misunderstood.

“My son is a non-eater. Picky eating could be probably much easier,” she said. “It’s not about a behavioural issue and it’s not about a mental health issue.

“It’s really more of hypersensitivity that leads to this fear of trying the food.”

The disorder was formally recognized in 2013, though before that was recognized as a pediatric feeding disorder for kids under six.

El Annan said she knew something was different about the way Mohammad ate since he was a baby. It was just last year that she as able to secure a formal diagnosis for Mohammad.

She said people with ARFID often don’t realize they’re hungry until they are starving — but that when they do eat, they don’t eat enough.

“This is the curve that we keep going up and down,” she said. “It’s really challenging, and tiresome for him.”

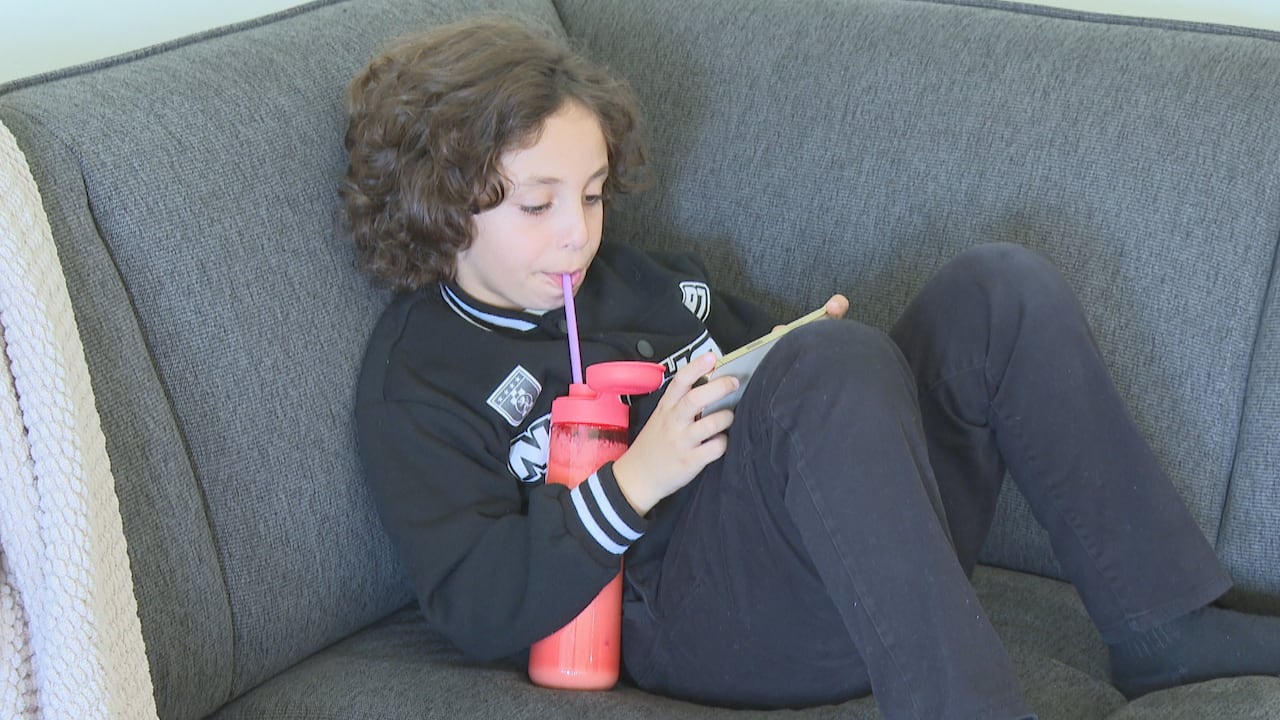

On a Tuesday afternoon, El Annan offered her son a smoothie: Milk with a wheat powder, banana and a vanilla pudding. Blending it up, she asked him about the thickness. Good, he said. The colour? Good too, Mohammad said.

Sipping away on the smoothie through a water bottle with a straw, El Annan decided to prepare an egg the way he likes it, at least right now: Hard boiled, with a little salt and lots of cinnamon.

Sitting next to him, El Annan counted how many times he chewed, with plenty of encouragement, and gentle coaxing for another bite or half-bite. The egg, more than half uneaten by the time it seemed Mohammad had had enough.

Small portions, breathing and facial exercises and taking more time with meals all help, she said, as do regular sessions with a therapist.

ARFID is challenging for her, because of the time and intense effort that goes into making sure her son eats enough and receives enough nutrients, as well as getting him all the therapy and extracurricular activities that will help.

Mohammad said ARFID makes chewing and eating hard.

But he says he is learning more about ARFID and how to eat better.

“It makes me feel brave,” Mohammad said.

By speaking out, El Annan says she’s hoping to connect with more families whose kids struggle with ARFID, to get some recognition for the disorder in young children and support for more services in the community. There’s help available, but kids with ARFID need more.

She’s also hoping for more recognition within the education system, she says, because of the accommodations Mohammad needs at school, like additional breaks to eat.

Eventually, she’s hoping to start a program to help families with ARFID expose their kids to more types of food.

Most of the services that exist around ARFID are for older teens and adults, and what El Annan can access, isn’t covered by insurance and she pays out of pocket.

El Annan says the biggest misconception is that her son is just picky, or that this is something he can control.

“He tells me that, ‘This is for you, I’m trying it for you,’ because he’s seeing how much I’m giving him. And I’m like, you have to do it for yourself because this is for you to grow up and be strong … it will keep you healthy.”

It’s a misconception that Heather Leblanc says is common with the adult clients she sees.

Leblanc, a registered social worker with Bulimia Anorexia Nervosa Association (BANA) in Windsor, is on the team that treats clients with ARFID through outpatient programs. Right now, they have about 10 adults receiving treatment.

There are three main types, she said, and sometimes people with ARFID will have a combination of the three: Sensory sensitivity — like an extreme aversion to a food smell — fear of negative experiences, like choking or vomiting, or a total disinterest in food and lack of sense of hunger.

There aren’t Windsor-Essex specific estimates about ARFID, but a Canadian study identified 2.02 cases per 100,000 pediatric patients.

Leblanc said the condition can be debilitating: For kids, there are concerns about appropriate weight gain and maintaining healthy weight, as well as nutrients for proper growth.

In adulthood, if untreated, people with ARFID can lose hair and teeth or see their organs breaking down, as well as other medical complications because of nutritional deficiencies.

There are also social and psychological impacts: Depression and anxiety are common, and there are sometimes overlaps with autism and obsessive compulsive disorder.

“You might feel misunderstood. You don’t want to have to explain yourself,” she said. “It is really sad because the alternative is just to not engage in life. And for a lot of people, that feels like a safer option.”

Turns out, a lot of ideas about your body and dieting you had when you were a kid can impact how you feel about food today. Jennifer White is a clinical social worker with a focus on eating disorders. During Eating Disorder Awareness Week, White speaks with CBC Windsor Morning’s Amy Dodge about what parents can do to break that cycle of negative food thoughts and foster body acceptance for their kids.

Treatment for ARFID, she says, is very individualized but at BANA includes cognitive behavioral therapy with a team consisting of a psychologist, dietician, nurse practitioner and therapist with the goal of increasing “volume and variety” of food.

Services for youth with ARFID in the community start at age 11, and BANA specifically works with adults. But Leblanc said she’d urge parents to consult their pediatrician, and there are therapists and dieticians in the region that have training in ARFID.

The number one thing to know, Leblanc said, is that it’s not the person’s fault.

“Those who have it, the anxiety and the distress that they have around food is very, very real,” she said.

“My hope is that with people speaking out … people with ARFID and family supporting people with ARFID feel less shame and feel less alone.”

If you or someone you know is struggling with disordered eating, here’s where to look for help:

- Kids Help Phone: 1-800-668-6868. Text 686868. Live chat counselling on the website.