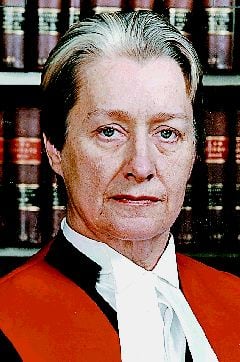

Decades ago one of B.C.’s top judges described the tension between the concept of Aboriginal title and the reality of private property ownership in British Columbia as a “cloud.”

Once on the “far horizon,” then-B.C. Appeal Court Justice Mary Southin said legal questions about the status of title on properties ranging from ranches to houses to Vancouver office towers had grown from the size of “a child’s hand” to “lower over the whole of the Province.”

Last week, just as Southin predicted it eventually would, the “cloud” touched down in Richmond.

A townhall full of homeowners who just learned they may have to share land title with the Quw’utsun (Cowichan) Nation gathered to hear the city’s mayor and lawyers explain the implications of a court decision very few have read, but on which nearly everyone has an opinion.

“The bottom line … is that Aboriginal title cannot co-exist with fee simple ownership [the legal name for private property title],” Richmond city solicitor Tony Capuccinello Iraci told the crowd at one point.

Except that it can and does, according to Victoria B.C. Supreme Court Justice Barbara Young, who awarded the Quw’utsun Aboriginal title this summer to between 300 and 325 hectares of land — including around 150 pieces of private property — just east of the Massey tunnel.

‘The government didn’t help here’

Young’s decision may go further than any other previous court rulings in addressing the seeming contradiction Southin identified all those years ago, but it’s still grounded in the kind of ambiguity that thrives in a courtroom, but falls flat in a packed room full of mortgage payers.

“When you’ve got court decisions — typically ones that deal with this degree of complexity and use all these arcane terms and are 400 pages long or whatever — unless the decision is really definitive, what matters is not the decision, but then how it’s interpreted,” says Andrew Petter, a lawyer and former provincial NDP minister of Aboriginal affairs.

Petter is not a fan of how the province or the City of Richmond have handled the fallout from Young’s ruling — in which he sees a call for measured negotiation and reconciliation between the Quw’utsun and the Crown, not hyperbole.

“The government didn’t help here,” Petter told CBC News.

“The government basically decided to play tough guy and by doing so, suggested that the judgment was a threat to private property.”

‘It inflames and incites’

The province and the City of Richmond are both appealing Young’s decision, as are the other parties to the ruling. In the meantime, they have announced plans to ask for a stay of proceedings — hoping to freeze the ruling Young had already suspended for 18 months.

In response, the Quw’utsun are also challenging the result, looking to win title to all 750 hectares — 1,846 acres — claimed at the launch of the lawsuit in 2014 as the site of a traditional village pre-dating the establishment of both British Columbia and Canada.

Capuccinello Iraci told the crowd the decision undermines the entirety of B.C.’s land title system, throwing the rights to millions of properties into question and calling on affected homeowners to share stories about the impacts of the decision to buttress the city’s legal case.

He effectively repeated arguments Young rejected in concluding that Aboriginal title to private property could not be displaced or extinguished.

“Richmond’s submission that a declaration of Aboriginal title will destroy the land title system and the [Land Title Act], wreak economic havoc and harm every resident in British Columbia is not a reasoned analysis on the evidence,” the judge wrote in her ruling.

“It inflames and incites rather than grapples with the evidence and scope of the claim in this case.”

‘Tl’uqtinus is very important to us’

Young’s lengthy ruling is as much a history lesson as it is a legal document, grounded in the deeds of men whose names make up a modern-day atlas of British Columbia: Douglas, Moody, Burnaby, Lytton, Seymour.

The judge heard oral testimony from the descendants of Quw’utsun elders who recalled the days the property at the heart of the claim was known to them as “Lands of Tl’uqtinus” — site of a village bountiful in berries, roots, fish, shellfish and game.

In her decision, Young says she assessed the oral history on a case-by-case basis, comparing and contrasting the memories of witnesses with expert and documentary evidence, including maps, surveys, notebooks and diaries yellowed with age.

“Tl’uqtinus is very important to us. It’s where we lived. It’s our home. That’s where we harvested many things,” Luschiim, an elected Cowichan Tribes Council member also known as Arvid Patrick Charlie, told the court. He was 72 when he testified in 2015.

“It’s very important to be able to live there again, live there again like we used to, to harvest our resources again like we used to.”

‘Moody acted in his own self-interest’

The roots of the Quw’utsun’s grievance are grounded in a promise British Columbia’s first governor — James Douglas — made in 1859 to exempt Indigenous settlements like Tl’uqtinus from sale or claims from settlers.

Instead of carrying out those directions, the man tasked with protecting what was supposed to be a Quw’utsun reserve — Chief Commissioner of Land and Works Richard Clement Moody — covertly bought two waterfront pieces of their land himself.

“Moody acted in his own self-interest and contrary to Douglas’ express directions and colonial policy, taking appropriated Indian settlement lands for himself,” Young said.

That “dishonourable” transaction set in motion a pattern repeated over the next half century as the Crown granted ownership of the land to “prominent, absentee settlers” who left it “largely idle and unoccupied.”

The land is worth billions today, comprised of lots owned by private landowners as well as the City of Richmond and the federal Crown, which has assigned administration of its property to the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority.

Citing Douglas’s original instructions and the honour of the Crown, Young said the province lacked authority to sell or distribute the land in the decades and centuries that followed.

‘This should not be a zero-sum game’

The Quw’utsun asked the judge to declare present-day title to land held by the Crown, the port and Richmond invalid and defective — but crucially, the First Nation did not ask the judge to make a similar declaration in relation to private landowners.

The judge weighed in anyway — responding to arguments from Richmond and the province, which claimed any ruling on the title over the rest of the land would necessarily affect the status of the privately-held property.

Their submissions were nuanced.

Richmond argued Crown grants of fee simple “extinguished” any Aboriginal title existing over the claim area, while the province said the grants “displaced” title on the private lands, asking Young to limit any declarations to land owned by the parties involved in the litigation — not the third-party homeowners.

If concluding that Aboriginal title co-exists with fee simple title on private property is a head-scratcher, Young says it’s important to note that “Aboriginal title and fee simple interests are not unqualified interests.”

Aboriginal title is a communal right to land that “cannot be encumbered, developed or used in ways that would prevent future generations of the group from using and enjoying it.”

And while fee simple title allows owners and their successors to “do with the property as they wish, within the limits set by the law,” it also has constraints including “environmental protection statutes, planning and zoning legislation, expropriation by the state.”

“This should not be a zero-sum game,” Young writes, echoing the author of a 2015 article titled Aboriginal Title and Private Property Rights.

“Both interests in land may be valid, and the exercise of the rights that come with those interests should be reconciled.”

Why weren’t they told?

So what next? No matter what the ultimate outcome, it won’t happen quickly.

The Quw’utsun case took 11 years to come to a conclusion, and proceedings at the B.C. Court of Appeal are only just beginning. After that comes the Supreme Court of Canada.

Beyond the objections of Richmond and the province, the Musqueam and Tsawwassen First Nations have also appealed — staking out their own interests in both the land and the right to speak for the descendants of its original owners.

Some of the private property owners who showed up at last week’s townhall have vowed to hire lawyers to represent their interests. A number of them asked Richmond’s representatives why they weren’t told about the proceedings sooner — an unexpectedly controversial question.

Back in 2017, Canada’s Attorney General sought an order requiring the Quw’utsun to notify third-party homeowners, but the judge overseeing proceedings at the time rejected the application after the Quw’utsun said they weren’t seeking title or possession of any private lands.

“However,” Justice Jennifer Power wrote, “my decision does not prevent any of the defendants from providing informal notice to private landowners if they wish to do so.”

‘The sooner the better’

One answer to the questions posed by Young’s decision may lie in a line of defence the province and Richmond attempted to mount arguing the rights of a so-called bona fide purchaser.

The argument would protect innocent, good-faith purchasers who buy property without any notice of underlying claims — directing any legal action against the original seller, which in the case of the Quw’utsun claim would presumably be the Crown.

Young found Richmond had “acquired” its properties through forced sales due to unpaid property tax — as opposed to “bona fide” purchasing.

And she didn’t want to let the province argue on behalf of third parties without them “having an opportunity to lead evidence and present their own arguments” — which means the bona fide purchaser defence and its implications remain untested.

Regardless, Young suggested, the duty to resolve any conflicting interests is likely to wind up back with the Crown.

“These interests may be resolved through negotiation, challenged in subsequent litigation, purchased, or remain on the Cowichan Title Lands,” the judge wrote.

“That is not a matter for this Court to address. B.C. and the Cowichan should be afforded space to reconcile these competing interests. It is an issue for the Crown and not the private landowners to resolve.“

Justice Mary Southin died in late September — with the “cloud” over the relationship of Aboriginal title to private property in British Columbia still looming.

Back in 2000, Southin said the issue affects all British Columbians, “be they rich or poor, of whatever stock of descent” — including “persons of aboriginal descent in British Columbia who hold land in fee simple.”

If they “cannot rest on their certificates of indefeasible title, they, their mortgagees, and, perhaps more importantly, their families who are dependent upon them for their economic well-being, should know,” Southin wrote.

“And the sooner the better.”