WARNING: This story details allegations of child abuse.

Taking the witness box in her murder trial for the first time, Brandy Cooney said she called the boy she and her wife were trying to adopt a “moron” and “loser,” used zip-ties to confine him in a wetsuit and locked him in his room.

Cooney told Superior Court in Milton, Ont., on Monday that she knew the 12-year-old was severely underweight in the fall of 2022 and recalled how he’d told her he was afraid he would die.

Cooney also searched “I hate my child” on her iPad two days before his death, she told the trial that began in mid-September.

But under questioning from her lawyer, Kim Edward, Cooney said she loved him, yet was frustrated with what she said was a lack of support from the Children’s Aid Society (CAS), therapists and doctors to help the boy.

“I hated the [boy’s] behaviours,” said Cooney. “I hated that we couldn’t be a functional family.”

She said she did the online search because she was looking for support from other frustrated parents.

Cooney and Becky Hamber are charged with first-degree murder of the 12-year-old, as well as confinement, assault with a weapon — zip ties — and failing to provide the necessaries of life to his younger brother.

Both women have pleaded not guilty.

CBC Hamilton is referring to the older boy as L.L. and his brother as J.L. as their identities are protected under a publication ban. The Indigenous brothers were in Cooney’s and Hamber’s care from 2017 until L.L. died in their Burlington home on Dec. 21, 2022.

The defence called Cooney as their first witness in the judge-only trial.

She defended how she and Hamber cared for the boys, who she described as having experienced neglect and trauma in previous homes that caused them to have behavioural challenges.

“Did you do anything to cause his death?” Edward asked.

“No,” answered Cooney.

Defence says boy would ‘erupt’

Cooney spoke warmly of Hamber, who she described as a detail-oriented organizer, and at times sounded emotional when speaking about the boys. Her voice wavered while she recounted how she found L.L. unresponsive on the floor of his basement bedroom, and then “dove” to him and performed CPR. He died in hospital later that night.

According to Cooney, she and Hamber were not informed by the CAS about the extent of the brothers’ “mental health issues” before the two began living with them.

But L.L. would “erupt out of nowhere,” as described by Hamber’s lawyer, Monte MacGregor, as he questioned Cooney. She said he’d harm himself, hit and kick, throw objects, scream insults, cry, and threaten to hurt pets, J.L. and the women. The “tantrums” could last for hours.

“It seemed uncontrollable,” said MacGregor. “It seemed frantic, almost like an animal that had been whipped and was responding with some unknown survival technique.”

Cooney agreed and said she responded with phrases like “you are loved.” She said she never harmed either boy.

“I always wanted them,” she said.

Edward questioned why Cooney had called L.L. names over text and in recordings. Those names included “douche, barfer, f–k face, moron, twat, it.”

“Not the greatest words, I understand that,” Cooney said. “I have an issue with my frustration language. I call most anything that. I’m not labelling my child that — I’m labelling their behaviour.”

Eating disorder caused weight loss, says accused

In the last year of his life, L.L. developed an eating disorder, said Cooney, and that meant he almost constantly regurgitated his food “for comfort,” causing him to lose a significant amount of weight.

About a week before he died in 2022, he weighed 48 pounds — less than when he was six years old, the court has heard. The couple never took him to the emergency room, even in late November, when L.L. was unable to stand, focus his eyes or speak coherently, and Cooney thought he may be hypothermic or, as she said in a text to Hamber, that he would suddenly die.

Cooney said L.L.’s psychiatrist had told them the hospital couldn’t help with his eating disorder and he needed to be admitted to a specialized program.

The psychiatrist testified last month. She said she repeatedly urged the couple to take L.L. to the emergency department.

By December 2022, L.L. was being referred to an eating disorder clinic. Cooney said she was hopeful he’d get in quickly. At a family doctor’s appointment, she said, she even made sure the scale was accurately capturing his weight.

“I know it sounds gross, but the lower his weight, the easier it might be to get into this eating disorder clinic,” she told the court. “I didn’t want it to read 50 pounds if it was actually 40 pounds.”

The doctor has testified he sent L.L. home, despite his weight, instead of to the hospital. Cooney said she left the appointment having no idea L.L.’s condition should have been treated as an emergency.

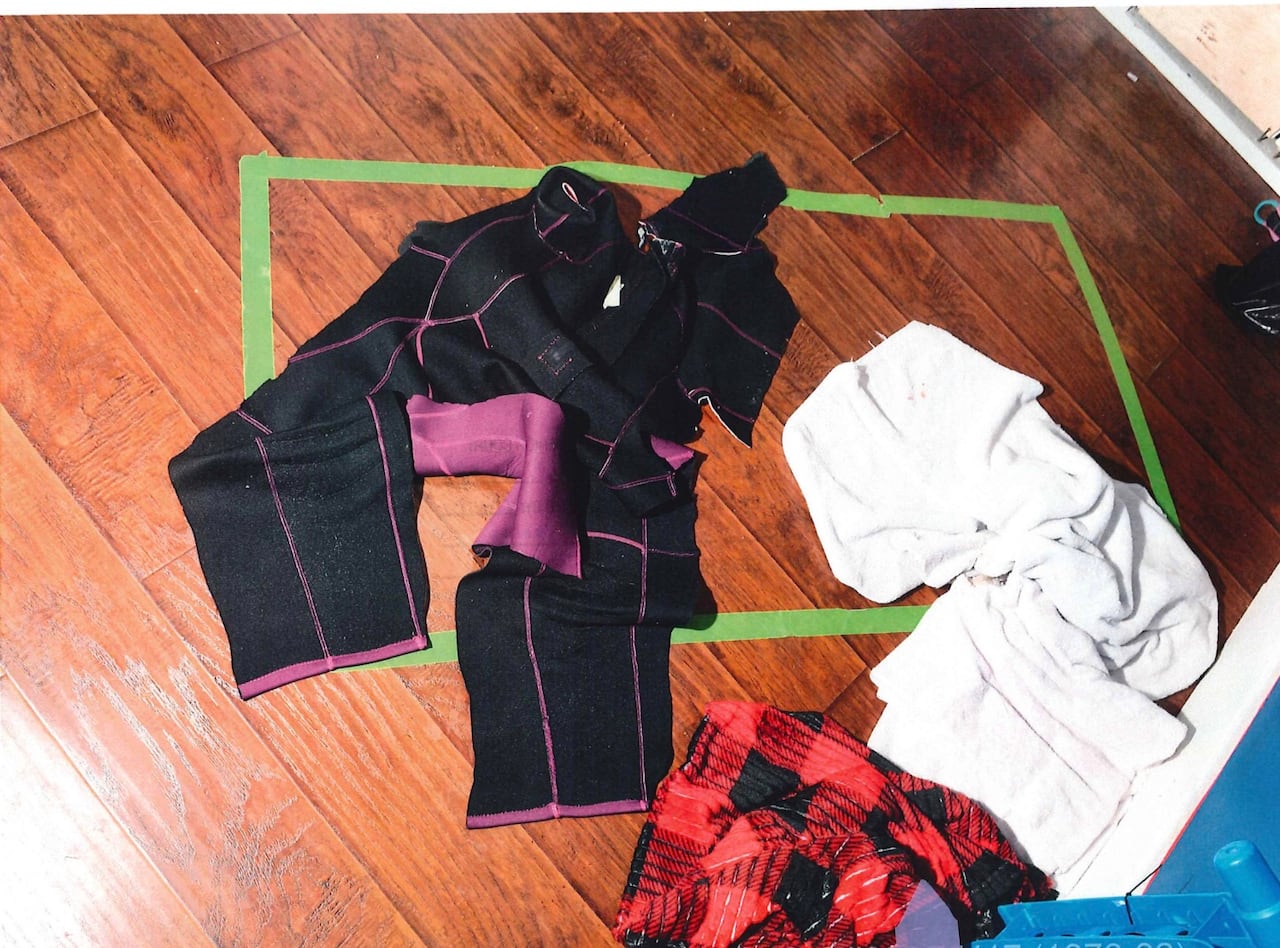

CAS knew about zip ties, wetsuits

Cooney was asked about a number of allegations brought up by the Crown during the trial that she attempted to explain.

J.L., now 13, testified he and his brother lived in increasing isolation. He said he was fed pureed food against his will, was forced to march up and down the stairs for hours, and occasionally had accidents because he wasn’t allowed out of his room to go to the washroom.

But Cooney said the women used zip ties to confine the boys in their wetsuits to stop them from urinating and defecating in the house, and L.L. from masturbating “quite a lot” at night. She said the boys were given pureed food along with regular meals and encouraged to do light exercise — techniques recommended by a therapist.

She described the wetsuits, made of thick fabric, as “a heavy hug on them all day.”

The couple did lock the boys in their rooms overnight, and confined them in tents on their beds to keep them safe and prevent them from self-harming, Cooney said.

The boys would be in their rooms each night from about 6 p.m. until the morning, she said, adding she’d wake them up in the middle of the night so they could use the washroom.

There were also cameras throughout the house to keep an eye on the boys, she said.

The CAS knew about the women’s use of zip ties, wetsuits and tents, said Cooney. She didn’t know if the worker had seen the locks outside the bedroom doors, but the women hadn’t intentionally hidden them, she said.

Another concern raised at the trial was that the CAS, therapists and doctors rarely if ever spoke to the boys alone. Cooney said they were trying to minimize the risk of contracting COVID-19, manage Hamber’s health issues and prevent the boys from being retraumatized by having to recount what Cooney said was past abuse and neglect.

Throughout 2022, they were trying to get L.L. into a residential treatment program to get a “proper diagnosis” and for the women to get some temporary “respite,” as MacGregor said. The CAS denied their claim.

“We were just trying to get help,” Cooney said.

The trial is set to continue today.

If you’re affected by this report, you can look for mental health support through resources in your province or territory.