On most summer Sunday afternoons, Michele Facchini would be nowhere near the sweltering hot, low, flat fields northwest of Ravenna, Italy, with a metal detector.

However, it was here he made an unexpected connection to Cape Breton’s Hector McDonald, a soldier who died in action in 1944.

The 49-year-old Facchini, a Second World War researcher and educator, usually spends summer weekends at home, reading diaries of Canadian soldiers and tracing battle maps.

On July 6, he took advantage of some cool weather, heading to the outskirts of the town of Russi, near the Lamone River.

There, in December 1944, nearly 10,000 Canadian troops advanced to push Nazi forces out of northern Italy. His research suggested a platoon had fought in the field, dodging bullets and bombs, side-stepping landmines, as the men pushed toward the river on frigid, water-logged terrain.

Facchini’s metal detector was set off by remnants of bullets and shrapnel from high-explosive bombs. Then the farmer whose land he was on brought him a few objects that had been collecting dust in a small warehouse on his land.

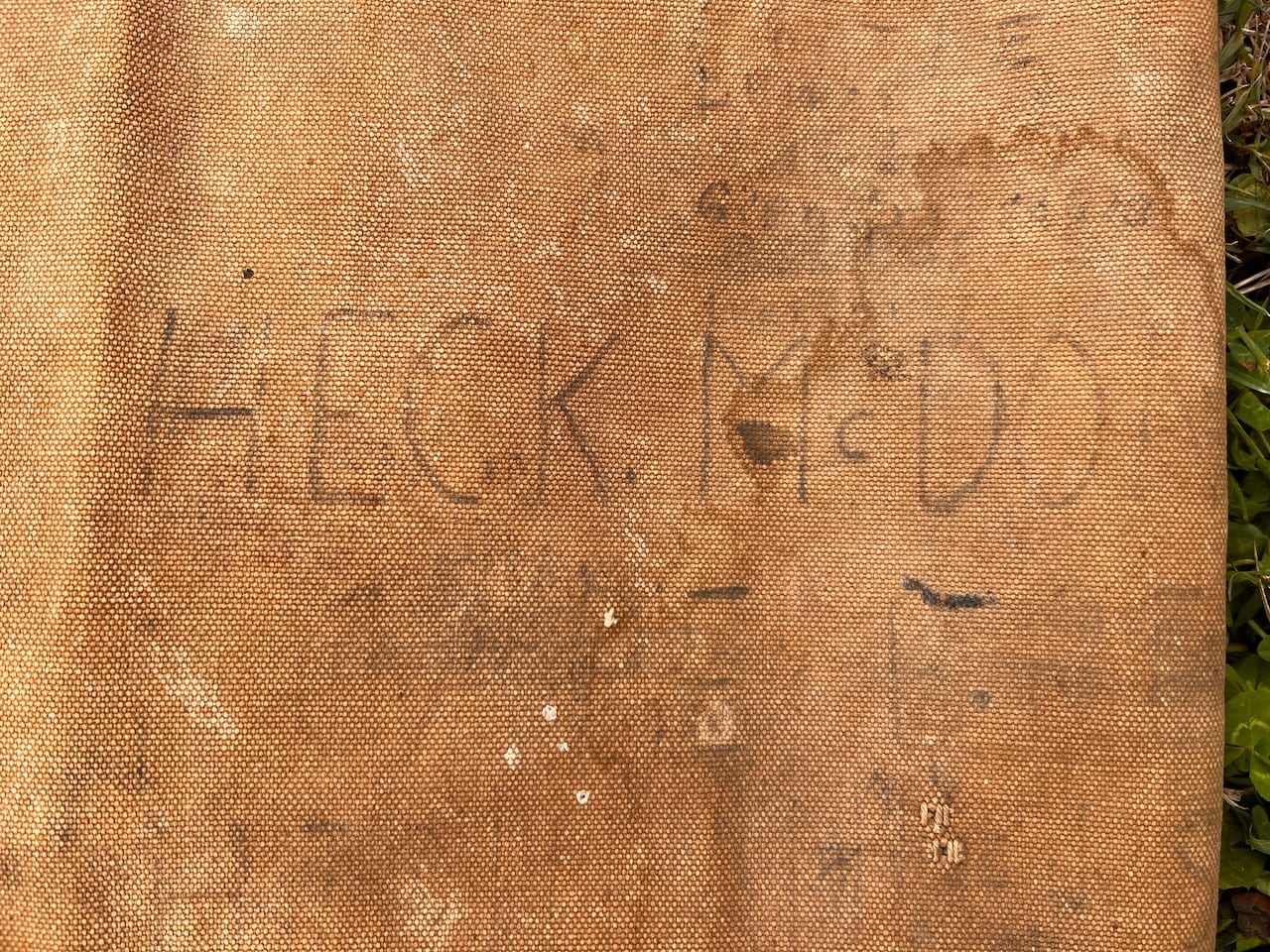

“That’s when I saw the duffel bag, the kind soldiers kept their personal effects in,” said Facchini. “It was covered in dirt, but underneath I could make out letters that spelled a name and numbers of a regiment.”

The accidental discovery would revive a story untouched for 81 years — and reconnect McDonald with a family that had never forgotten him.

No photograph of Hector Colin McDonald survives, but wartime documents sketch a portrait.

He was wiry at five-foot-nine and 137 pounds. He had hazel eyes and light-brown hair. His bearing is noted as “fair” and “correct.” He was the third of six children.

He was a young man who left school in New Aberdeen, Cape Breton at 15 to work in the Dominion Coal Company mines, as most of the men in his family did, hoping one day to become a welder.

Instead, in late 1941, at age 25, McDonald enlisted to fight in the Second World War, like thousands of young Canadians, because, as noted in his file, it was “the right thing to do.”

He joined the North Nova Scotia Highlanders and went on to fight his way through some of the grimmest battles of the Italian Campaign.

They included the Allied invasion of Sicily, the landing at Reggio Calabria mainland Italy, the brutal street-to-street combat in Ortona, and the grinding effort to break through at Monte Cassino.

Then came his last — the freezing, mud-choked advance north to take the Lamone River. They were sure it would take two days, but it took 12. In all, 548 Canadians lost their lives freeing Ravenna and the area.

McDonald, a lance-sergeant, marked each of his battles on his duffel bag. Some names are still legible. “Sicily. Italy. Ortona. Cassino.” Others have faded.

Among the unrecorded assaults he survived was the accidental Allied bombing of McDonald’s own regiment on Dec. 3, caused by outdated intelligence on their location.

A week later, just over a month before his 29th birthday, the Cape Bretoner was killed by a mine planted by retreating German forces on a small bridge over the Lamone River. The date of death was recorded as Dec. 13, 1944, but Facchini says the date likely reflects when his body was retrieved, two days after several soldiers stepped on the bridge mines.

He was buried with other fallen soldiers in a nearby farmer’s field before being interred in the Ravenna War Cemetery in 1946.

When McDonald died, he was likely still engaged to Elizabeth Wales, a Scottish woman he had met while overseas. Before being deployed on the Italian campaign, he had asked for leave to marry her. Among his personal objects was a rosary that, according to a chaplain’s memoir, she had given him.

“Her name was Elizabeth Wales and she lived in the mining quarters of Glasgow,” said Mariangela Rondinelli, a teacher and expert on local Second World War history who founded Wartime Friends, a group dedicated to honouring Canadians who fought and fell in Italy. “We know everything about this woman, her father’s name, her address, but we haven’t been able to find her family.”

Rondinelli and Facchini are part of a small network of Second World War researchers who have spent years documenting the stories of the mostly Canadian soldiers who fought in the region, often reuniting descendants with the communities that sheltered or helped them.

One member of the group, Raffaella Cortese de Bosis, helped verify McDonald’s identity and then tracked down his family — no small feat with a name as common as McDonald.

Her search took weeks and eventually led her to his great-grandniece, Kim Pyke, a Canadian Armed Forces veteran in Kingston, Ont.

“You have to be careful when you get in touch with possible relatives,” said Cortese de Bosis, “because sometimes the person caused pain to the family, had another wife, that kind of thing. But when I contacted Kim Pyke, she got back immediately, with ‘Hector McDonald was my great- uncle.’ That’s when the tears started flowing.”

“My mom and two brothers are still alive and they’re waiting with bated breath to see the bag. It’s pretty emotional,” said Pyke.

A ceremony was held in Russi on Saturday with relatives of McDonald in attendance.

Pyke was unable to make the trip for personal reasons, but her daughter Stacey Jordan, 23, travelled to Russi to take part in a local ceremony to honour the man the family affectionately called “Heckie,” where she was given the bag.

“A discovery like this is extraordinary on its own,” said Jordan, “even more so being someone in my blood line, but also coming from a family with so many people in the military, both parents, my grandfather and uncle. It does really hit close.”

Many family members still live in Glace Bay, some just doors away from Hector’s home in what was then a row of mining company houses, she said.

In a coincidence, another young relative, Cain Risold McDonald, 14, of Creston, B.C., had just submitted a school project on Hector when the duffel bag surfaced.

“I was pretty excited and disappointed at the same time because I could have put the duffel bag in the report as well,” he said of the discovery. “But it was really cool that my report came out and a month later they found his bag.”

Facchini calls the discovery 81 years after Hector McDonald’s death “absolutely one-of-a-kind.”

“For me, it’s not about the object,” he said. “I never go to flea markets looking for paraphernalia.

“It’s about the men who suffered, who carried on and who sacrificed so much. This isn’t just a duffel bag. It belonged to a Canadian who travelled across an ocean to fight against a dictatorship, Nazism and Fascism. His story matters.”

MORE STORIES