Warning: This story discusses school violence, sexual assault and suicide.

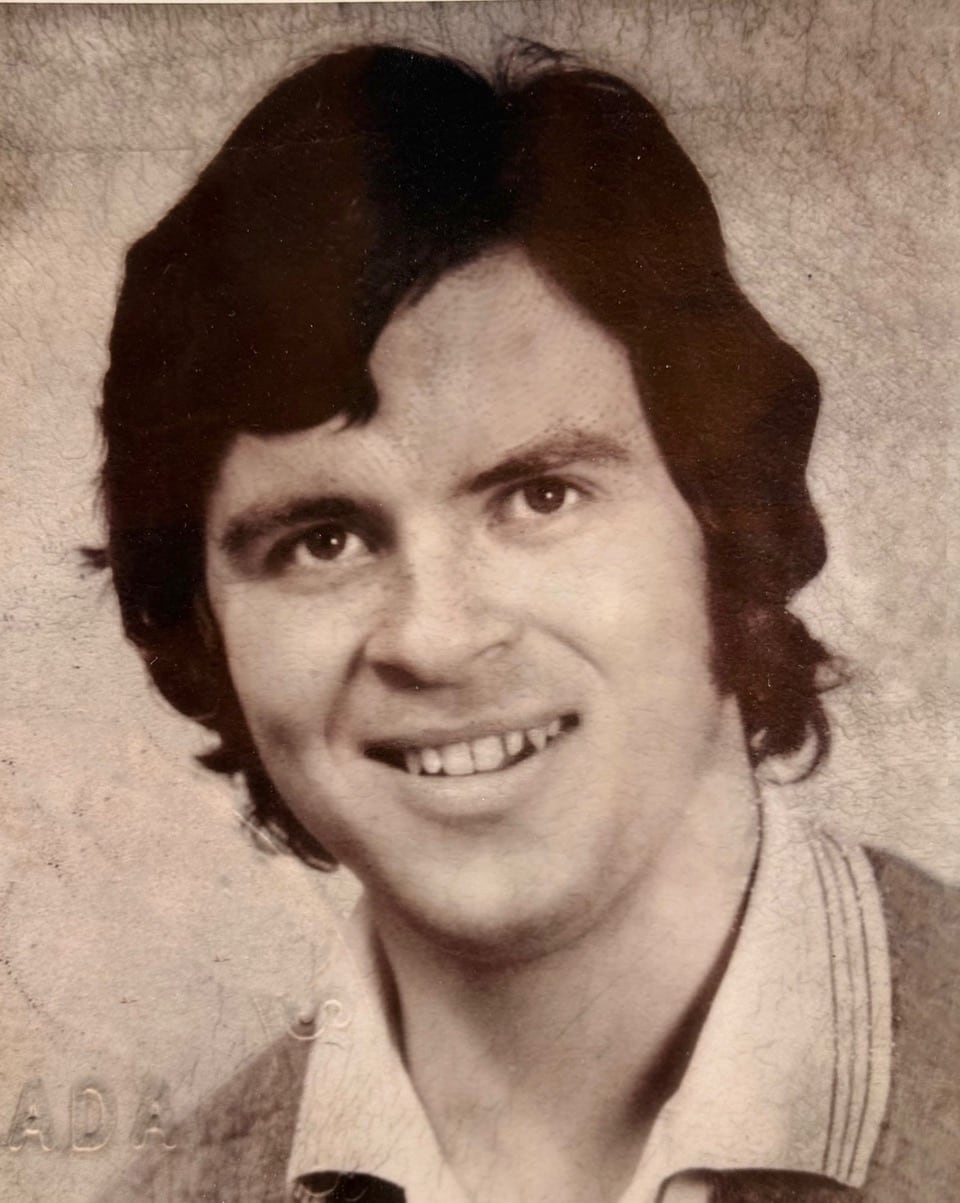

For decades, the family of an Ottawa student killed in a historic high school shooting has largely kept their memories of that traumatic time in what one sister calls “the memory box.”

Now, as the 50th anniversary of his tragic death approaches, the contents of that box are spilling out.

On Sunday, the family of Mark Hough — who never made it to his 19th birthday — will meet on the west side of Ottawa’s Rideau Canal and gather around a simple wooden bench they had dedicated to him earlier this year.

The memorial is an acknowledgement of Hough’s life, his sister Lynne McArthur says. But it’s also a reminder that “bad things can happen anywhere, even in Ottawa.”

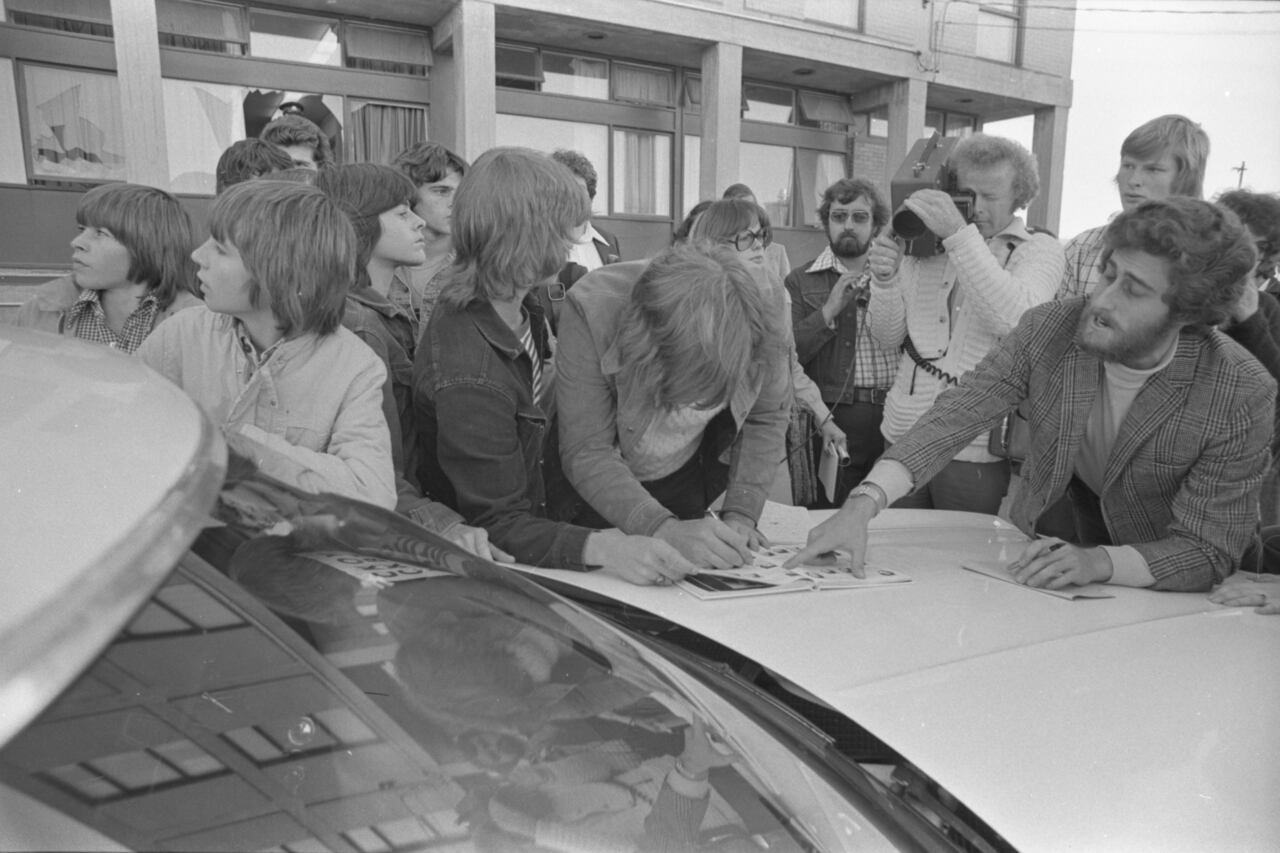

On Oct. 27, 1975, Hough and several other students in a packed religion class at St. Pius X High School were shot by a deeply troubled classmate who had raped and murdered Kim Rabot, a girl from a different school, at his home earlier that day.

With the exception of the gunman, who took his own life, every other victim of the classroom attack — one of Canada’s first school shootings — survived.

But Hough died over a month later in hospital, bringing the day’s total death toll to three.

“From the moment I found out that Mark died, I put him out of my mind because it was too painful to do otherwise,” McArthur says.

But in the leadup to next week’s anniversary, McArthur, her two sisters and a cousin who considers Hough his hero have joined Hough’s St. Pius classmates, along with those who knew Rabot at Glebe Collegiate Institute, in opening up to CBC for a four-part exploration of the murders’ painful legacy.

“I think the family will agree it’s time to move on from the grief and tragedy of that day,” McArthur says.

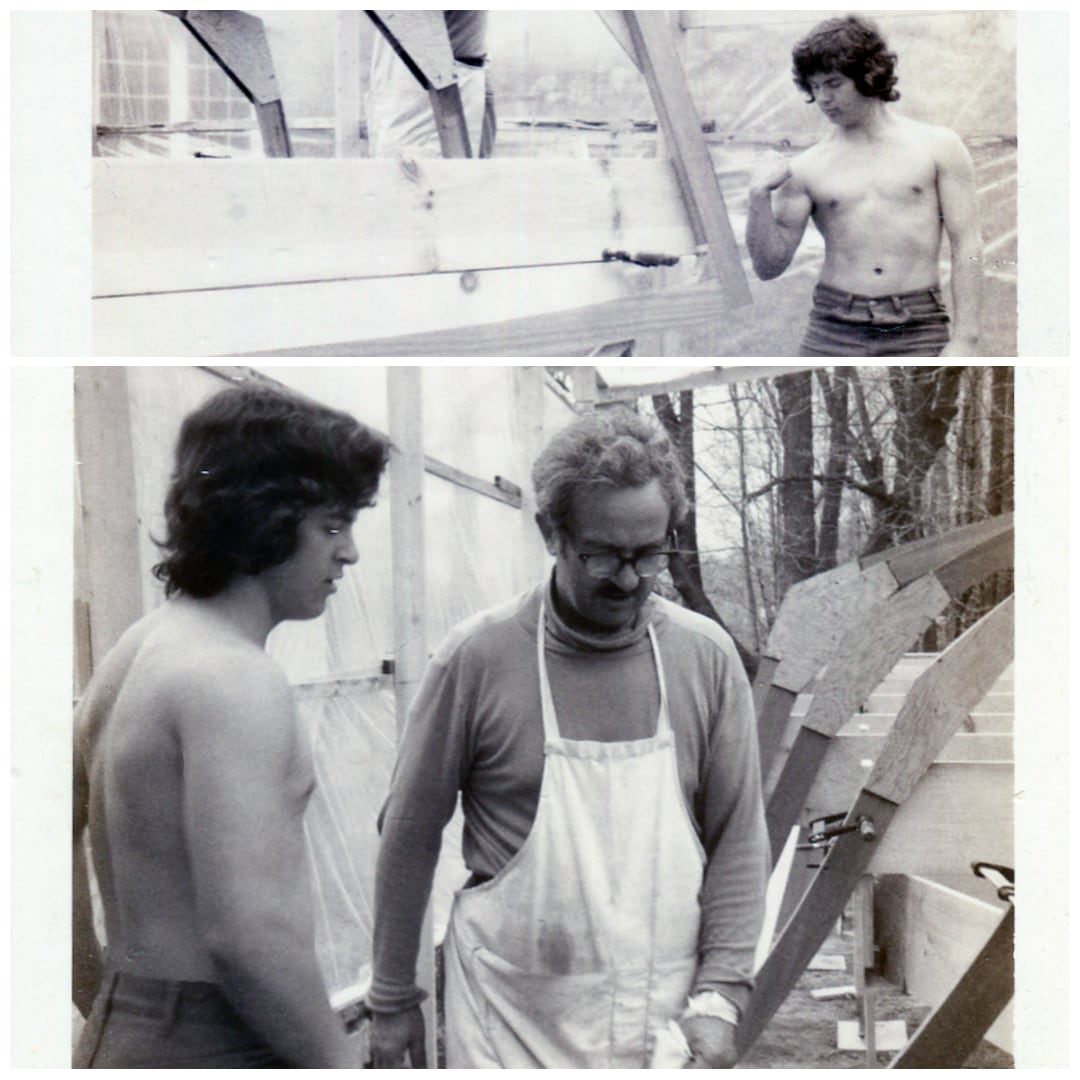

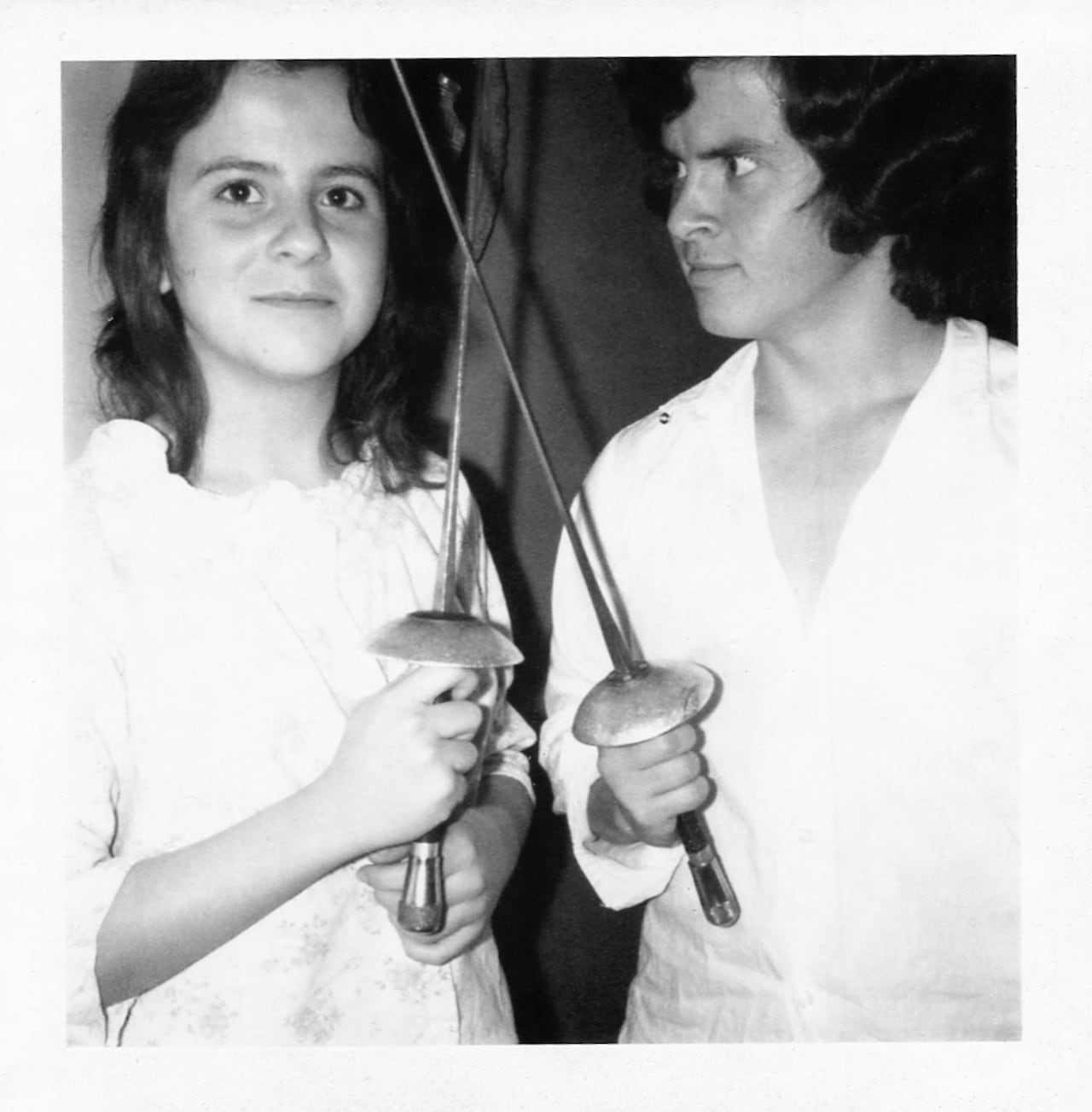

Mark Hough was a gifted hockey player and kind soul who was taken far too soon, his school friends say.

Part 3: Leave the ugliness behind

At 18, Mark Hough, pronounced “Huff,” was the second youngest of five children.

His eldest sister, Teri Bowles, says her brother’s unexpected death was so “black and ugly” the family could hardly breathe for a very long time.

“We all moved on through our lives: getting married, having children, being happy, doing well,” she writes in a statement to CBC.

Until recently, “I hardly ever went into the memory box. But there it was.”

McArthur, who was also older than Hough, still hasn’t visited her brother’s grave and only recently sat on the bench for the first time.

“It has taken this unfathomable amount of time to learn what happened, perhaps partly because contemplating the what-ifs would have been too traumatic earlier,” she says.

The Houghs’ father was a lawyer and Hough planned to follow in his footsteps.

“He was in Grade 13 because it would help this ambition,” McArthur says.

After Hough died, McArthur went to law school in his place. Though she didn’t follow that career path, one of her cousins, an Ottawa lawyer named Mark Power, is named after Hough.

So is the first son of Hough’s cousin and close friend Al Hough.

“Mark was my hero,” Al Hough says of the teen who taught him how to swear and throw a football.

“With a family never shy to speak and never hesitant to share an opinion, the events of October 27, 1975, have been met with a deafening silence. As time marches on, I have a better appreciation of it,” he adds in his own statement to CBC.

‘We all remembered where we were’

The day Hough was shot was “like a 911, or the JFK assassination, in the sense we all remembered where we were and what we were doing at the time when it happened,” Teri Bowles writes.

Janet Hough, the youngest of the family, was closest in age to Hough — only 17 when her brother died in hospital. His condition had wavered in the month after the shooting.

“We were told that he was going to be fine. Then we were told he wouldn’t make it. Then he would be fine, but with some deficits. Then that he could die at any moment,” Janet says.

“Time stood still. We collectively held our breath.”

Hough’s death was announced on Day 1 of a coroner’s inquest into Rabot’s murder and the shooting.

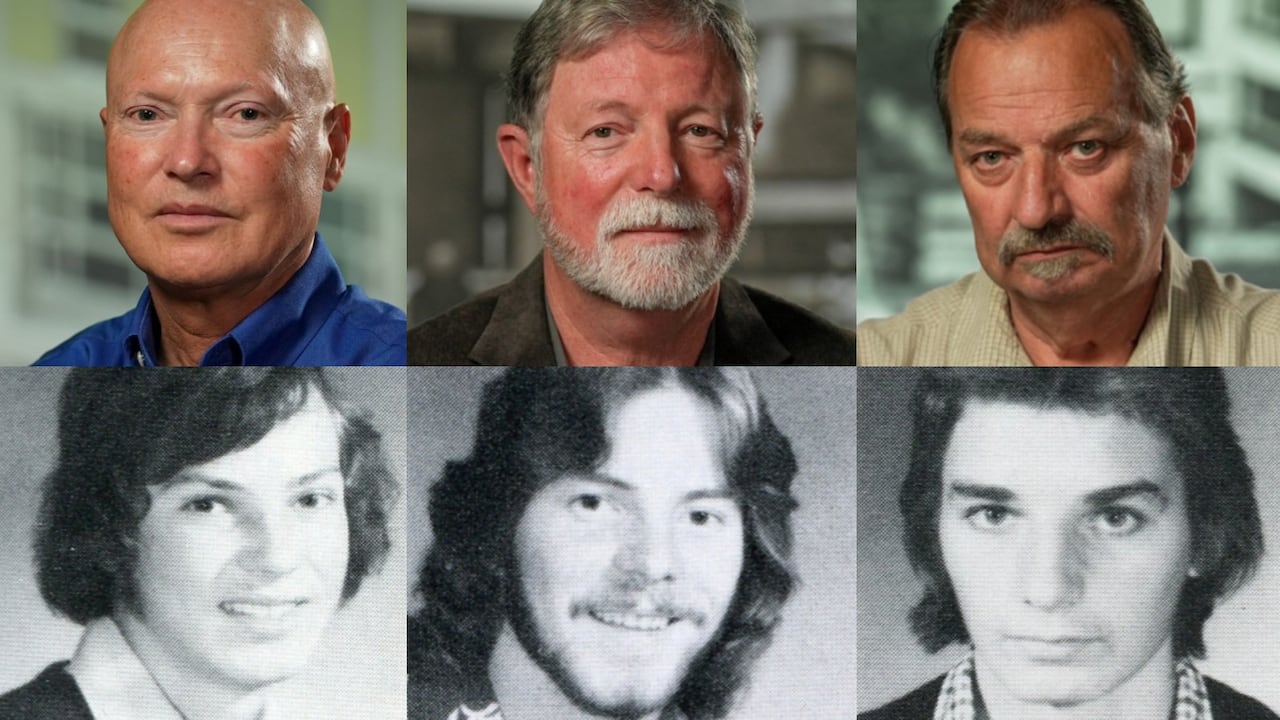

Liam Maguire, a Grade 11 St. Pius student who was in the school cafeteria when Hough was wounded in the head in Classroom 71, says Hough’s death probably shook him up more than the day of the shooting “because there was a finality to it.”

Maguire, who grew up to become a hockey historian, remembers taking the bus to St. Pius with Hough. Maguire was just a “tiny little human” at the time, but the good-looking Hough would sit next to him sometimes and ask, “How’s hockey going, Liam?”

“Mark Hough was an outstanding Junior A hockey player, struck down in his prime. I’m not saying he would have made the NHL, but the guy was damn good,” Maguire says.

Hough’s hockey club set up a memorial tournament where Hough’s parents presented the cup to the winner for several years.

His peers from school came by the house and presented the family with a plaque honouring “Hough’s outstanding friendship and spiritual achievements.”

It hangs in a corner of McArthur’s bedroom.

‘Put it all in the past’

On the day of the shooting, one the Hough family’s friends from St. Pius, Bernie Runstedler, was so hungry for information about Hough and the other wounded students that he says he stole a pair of hospital scrubs so he could visit the critically injured Hough in his room.

Runstedler’s in-laws are buried at Pinecrest Cemetery, not far from Hough’s own final resting place. So when Runstedler goes to the cemetery, he visits Hough’s gravesite, too.

“A person never really dies if somebody remembers them,” he says.

After it was learned that Robert Poulin, Hough’s classmate and killer, bought his gun at a Giant Tiger, McArthur refused to step inside the retail chain for a long time.

“I thought I was the only one,” Janet Hough says.

Al Hough remembers talking about his cousin’s death during his job interview with the RCMP, where he’s now worked for nearly 40 years.

“The violence of that day has contributed to shape my life,” he writes.

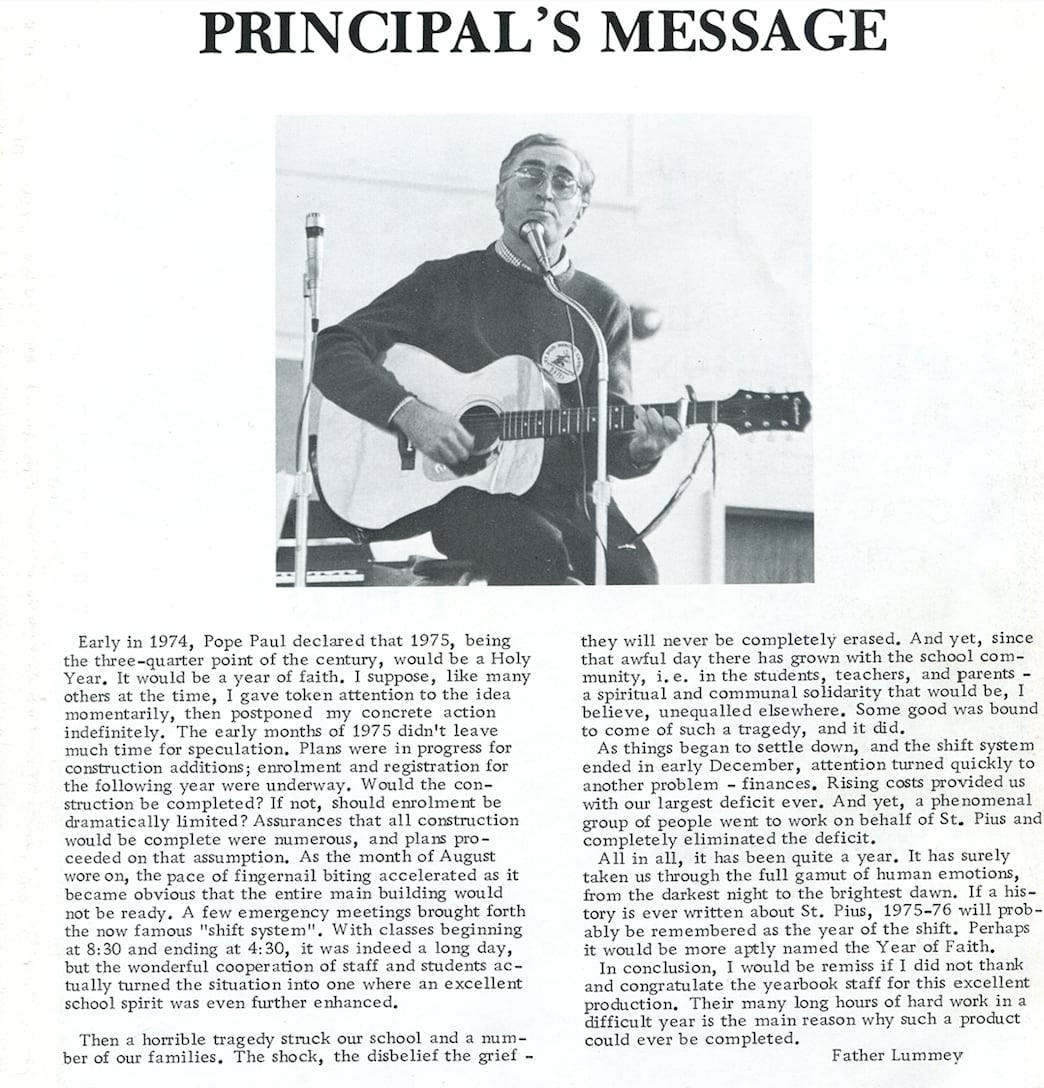

Below: The St. Pius X High School principal’s introduction to the yearbook for the year the shooting took place.

Runstedler says his family and the Houghs gave the school a framed photo of Hough, hoping they would hang it on the wall. The previous year’s yearbook had featured a tribute to a student who had died — incidentally, the brother of one of the other students wounded on Oct. 27, 1975.

But the 1975-1976 yearbook featured no dedication to Hough.

“I’ve never, ever seen that picture [up],” Runstedler says. “Ever.”

Janet Hough quit school before the semester was over. She doesn’t remember anyone mentioning her brother or the shooting when she briefly returned to St. Pius.

“Carry on, put one foot in front of the other, put it all in the past: that was the common understanding of how best to move on. An understanding shared by me,” she says.

In an emailed statement, the Ottawa Catholic School Board says it understands many families feel their loved ones were not adequately remembered at the time.

“While we cannot change the past, we have expressed openness to exploring future-focused recognition — such as a scholarship — with the Hough family, provided it aligns with trauma-informed best practices.”

Picking a scab

As the years went on, the coming of fall was the hardest, Janet Hough says.

“I drank too much, especially every year as October approached. I can’t explain what that felt like, so I won’t try. I stopped drinking when I was 30,” she says.

“It was only when I was in my early 40s that I realized the anniversary had almost passed without my noticing and that I was able to breathe.”

Last year, when Teri Bowles’s daughter Stefanie Bowles — one of several nieces and nephews Hough never met — proposed the memorial bench by the canal, Janet Hough says it felt like picking at a scab.

“Others could do it,” she says of her relatives’ plans, “but I didn’t want to hear anything about it.”

Janet Hough still doesn’t see the purpose of the bench — Mark did nothing heroic that day, she says. But she has a less visceral reaction to it now.

“Someone said, it’s just remembering Mark. I guess I’m OK with that.”

Lynne McArthur says the family will gather there on Sunday not in sadness but in loving remembrance of Hough’s life.

Or as Teri Bowles puts it: “We’ll celebrate [my brother], and leave the ugliness behind.”

This story is the third in a four-part series.

Part 1 examined the events of Oct. 27, the coroner’s inquest, the debate about gun control and the experience of the Poulin family. Click to read the story here.

In October 1975, two Ottawa high schools were rocked by murders committed by a troubled student who then took his own life. As the anniversary approaches, CBC is looking back at the changes, both personal and societal, that took place in the event’s wake. (Videography and editing by Mathieu Deroy. Production design by Michel Aspirot.) (Thumbnail photo: City of Ottawa Archives, Ottawa Journal, 028395)

More on the larger story from CBC’s This Is Ottawa podcast:

Part 2 remembered Kim Rabot. Click to read the story here.

Seventeen-year-old Kim Rabot was the first murder victim in a tragic series of events on Oct. 27, 1975, that culminated in a fatal shooting at an Ottawa high school. For the last quarter-century, one of Rabot’s friends has worked to ensure she is remembered as more than just the victim of a heinous crime. (Videography and editing by Mathieu Deroy. Production design by Michel Aspirot.)

Part 4 on Oct. 26 will focus on the survivors of the St. Pius X High School shooting.

If you or someone you know is struggling, here’s where to look for help:

If you’re worried someone you know may be at risk of suicide, you should talk to them about it, says the Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention. Here are some warning signs:

- Suicidal thoughts.

- Substance use.

- Purposelessness.

- Anxiety.

- Feeling trapped.

- Hopelessness and helplessness.

- Withdrawal.

- Anger.

- Recklessness.

- Mood changes.

Producer: Jen Beard

Videography and editing: Mathieu Deroy

Production design: Michel Aspirot

Copy editing: Alistair Steele