Carved into the Tyndall stone above the arched entrance to Winnipeg’s first public library are the words “Free to All,” but for the past 11 years, it’s been closed to everyone.

Now, as the former Carnegie Library on William Street turns 120, it’s about to begin a new chapter.

“It absolutely does feel like a new beginning, and it’s a testament to the building’s resilience,” said Cindy Tugwell, executive director of Heritage Winnipeg.

The 37,350-square-foot building at 380 William Ave. is set to undergo a $22.8-million renovation to make it a state-of-the-art archives facility, with a climate-controlled vault, to preserve and display Winnipeg’s historical records.

Construction is slated to begin sometime this fall, with a reopening in 2027.

“This building is grand,” Tugwell said, and putting the archives in “an appropriate landmark heritage building” shows the city cares about its history and its heritage.

“Education is key to the success of society. We look to history — to learn who we are, where we’ve come from, what things have been done, what mistakes may have been made — in order to look to the future to do it right,” she said.

“Our history is our soul, and we really have to tell those stories.”

Winnipeg’s first public library hits 120 years and is set for a new chapter with a $22.8-million renovation to make it a modern facility to store Winnipeg’s history as the city archives.

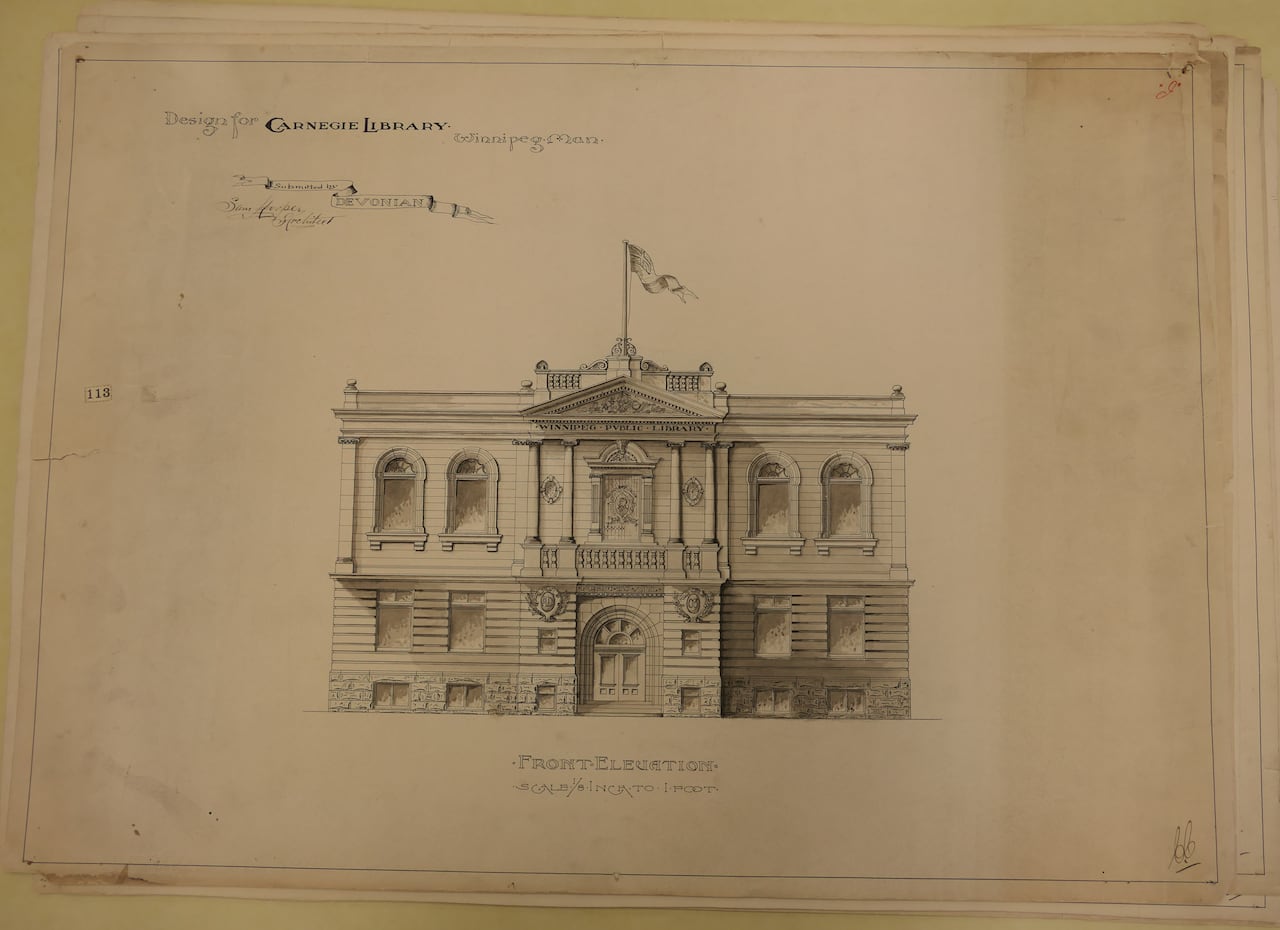

In 1901, provincial librarian John P. Robertson wrote to American philanthropist Andrew Carnegie to request funding to establish Manitoba’s first public library building.

At that time, Winnipeg was booming and so was the demand for books. A simple lending library was based in city hall, with small branch stations located in drugstores, missions, schools and hospitals.

A dedicated space was needed, and Carnegie granted $75,000 after the city promised land and annual operating funds.

Carnegie, who famously believed “the man who dies thus rich dies disgraced” and gave away most of his wealth, funded 2,509 libraries worldwide, including two more in Winnipeg: St. John’s and Cornish, both of which opened in 1915.

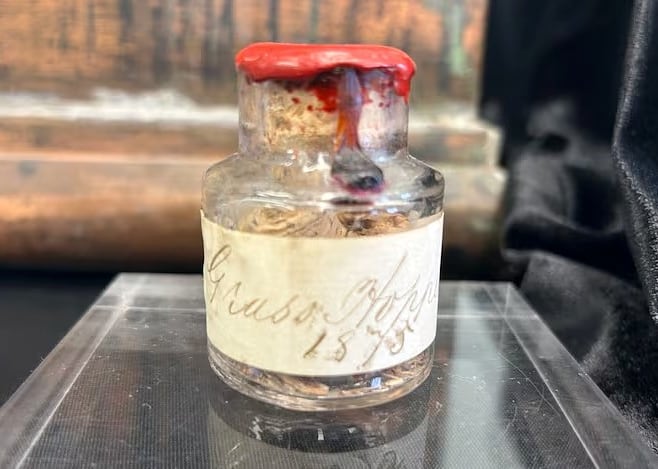

The William cornerstone was laid in November 1903 and contains copies of the city’s daily newspapers, postage stamps, coins and correspondence between Carnegie and the city, says a Winnipeg Daily Tribune from that day.

Opening day was filled with the hoopla of an honour guard and viceregal party.

Gov. Gen. Earl Grey was given the first library card and borrowed the first book. There are no reports on the book he chose, or if he returned it on time.

Carnegie libraries often contained a caretaker apartment suite and Winnipeg’s was no different.

James Simmons lived with his wife and four children in the basement’s northeast corner as he maintained the boiler system. It was long ago turned into storage space.

The library was enlarged in 1908 with an additional $39,000 from Carnegie, and by 1910, it was the second-largest library in Canada based on volume of books loaned.

It remained the city’s flagship library until 1977, when the Centennial Library (now Millennium) opened. Carnegie was closed and the city began moving its archives in, but public outcry prompted its reopening as a branch library in 1978.

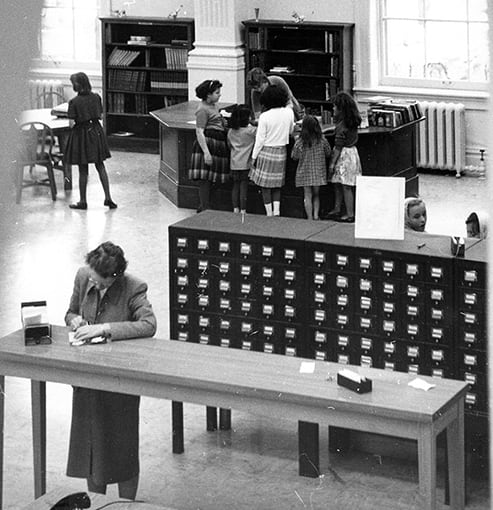

It served as a combined archives and library until 1994, when the latter was shut down and the former fully took over.

But the archives were forced out in 2013, when a rainstorm flooded the building, which was undergoing renovations and had gaps in the roof.

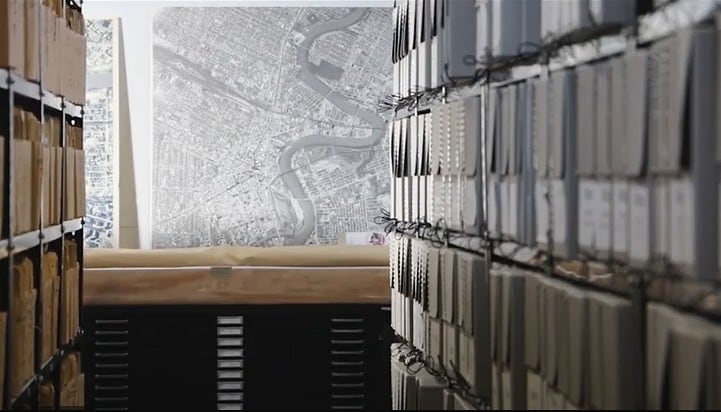

Since then, its wealth of materials, some dating back 154 years, and its staff have been housed in an industrial warehouse on Myrtle Street, off Notre Dame Avenue.

The oldest items are two photos of a muddy Main Street, with sparse wooden buildings, taken in 1871 and 1872.

There are records from 1874, tracing the city’s development through bylaws, assessment rolls, drawings, maps, letters and other artifacts, such as time capsules recovered from various buildings, while council minutes and correspondence paint a picture of residents’ concerns of the time.

Myrtle was meant to be temporary, but the cleanup at Carnegie and debate about whether to spend the money to move the archives back in has resulted in more than a decade passing.

Meanwhile, Myrtle is cramped. There’s 10,000 linear feet of records, including from the 12 municipalities that merged in 1972 under the Winnipeg banner.

Sarah Ramsden, Winnipeg’s senior archivist, says it’s one of the most complete municipal collections in Canada. But it’s not all there. Myrtle’s limitations mean overflow records are kept at yet another city warehouse.

Myrtle also has no temperature or humidity control, no space for preservation treatments on fragile documents, no space for public programming and little space for visitors — those who actually find the unmarked corrugated metal-clad building.

According to a 2016 report from the city, archive visits have declined significantly.

“That’s a catastrophe of a location,” said Tugwell. “We’ve been quite worried not only about this building, but the archives themselves. They’re invaluable to the city.”

While the city studied its options, the National Trust for Canada listed Carnegie as one of the Top 10 endangered buildings in the country.

In the end, a 2020 city report outlined the costs, archive needs and public feedback, ultimately deciding that renovating the Carnegie is best.

“This is the perfect building for it — the perfect fit,” Tugwell said, highlighting its central location just down from city hall, whose records it protects.

For Ramsden, it means bringing everything back under one roof and having “room for growth,” so they can once again accept materials and properly care for it all.

“We’ll also have much larger research space for members of the public to access material, and we’re excited to have public programming space as well [for] events, lectures, film nights,” she said.

“And exhibit space, too. We’ll finally have more of our records and stories of Winnipeg on display for people to engage with.”

It all means honouring the engraving above the door.

“It really embodies Carnegie’s philosophy that public access to knowledge is a public good and ultimately makes for a better world,” Ramsden said. “That mission still matters today.”

Some might criticize the city’s decision to spend so much money on a physical space when records can be digitized, but Ramsden said that’s a time bomb.

Not only is digitization resource-intensive and costly, it isn’t about preservation, because ultimately, digital records deteriorate. Then you’ve lost everything.

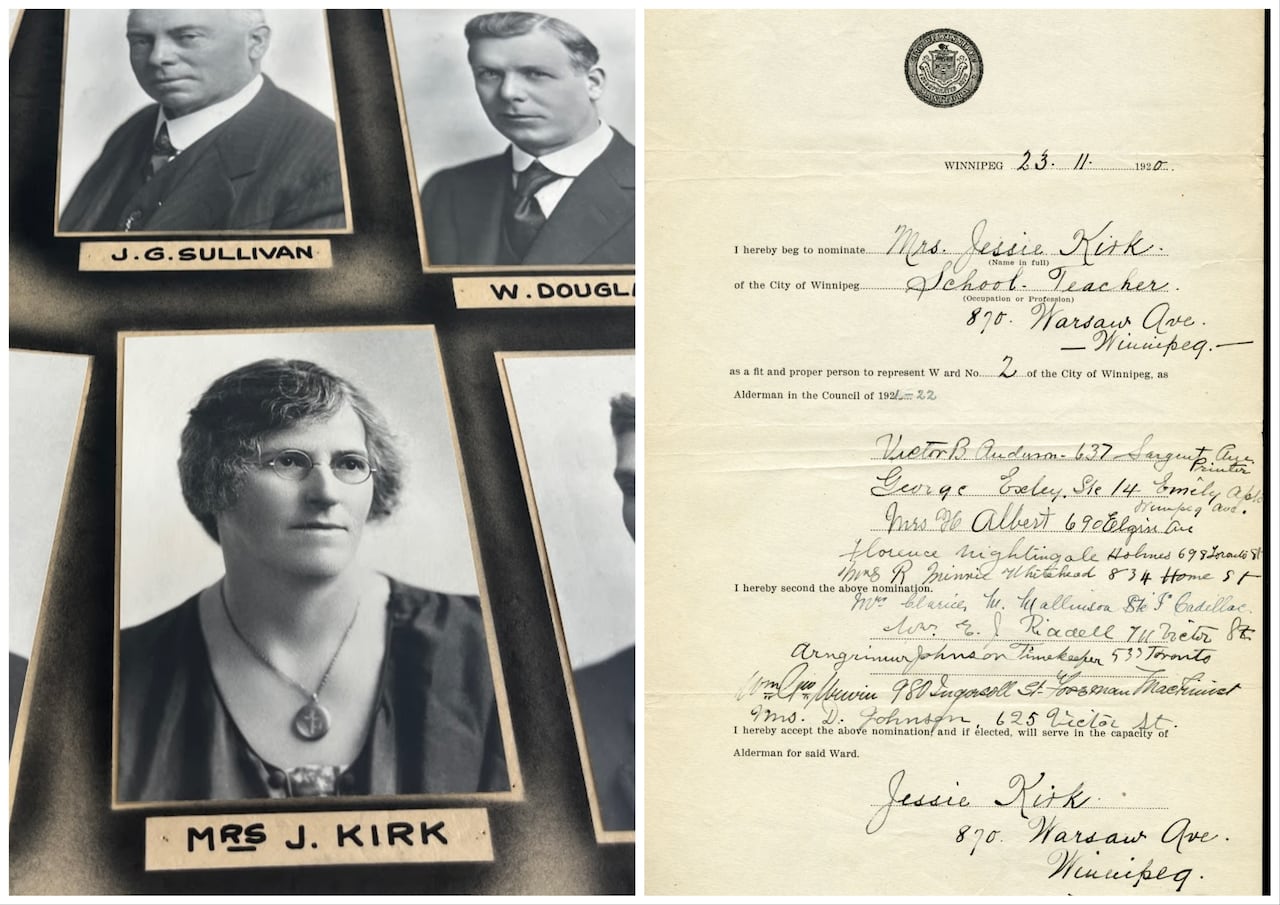

There’s also something that doesn’t translate in digitization, Ramsden said, using the 1920 nomination paper for Jessie Kirk, the first woman elected to Winnipeg council, as an example.

“Hers was more crinkled than the others, more well-worn. You just kind of get the sense … it was really passed around and looked at,” she said. “That information is lost when we just digitize.”

When it’s the actual item, “it’s a different experience and you engage with the record in a much different way,” she said.