The Sunday MagazineHow stadium concerts changed live music, from The Beatles to Taylor Swift

If Mary Grace Bova could choose to relive just one day in her life, she wouldn’t hesitate for a second.

It would be August 15, 1965.

She was just 14, sitting in the “very overwhelming” stands of Shea Stadium in New York City, when The Beatles ran onto the field.

“You just saw them with your eyes in-person, it was just like something I’ll never forget,” Bova, who is now based in Pennsylvania, told CBC’s The Sunday Magazine.

“All I remember is screaming and crying and sweating.”

That night, at the the height of Beatlemania, the group also known as The Fab Four performed a 12-song set in 30 minutes. More than 55,000 fans packed into the stadium, breaking records and redefining what a live concert could be.

The concert was “rightfully seen as a milestone,” said Steve Waksman, a professor of popular music at the University of Huddersfield in the U.K. The stadium’s crowd “was on a scale that was really, almost unprecedented for this sort of event.”

Now, as the legendary show marks its 60th anniversary, the excitement around massive stadium shows has only grown.

According to Live Nation, over 145 million fans attended more than 50,000 events in 2023. Much of that momentum was driven by massive stadium tours from pop stars like Taylor Swift.

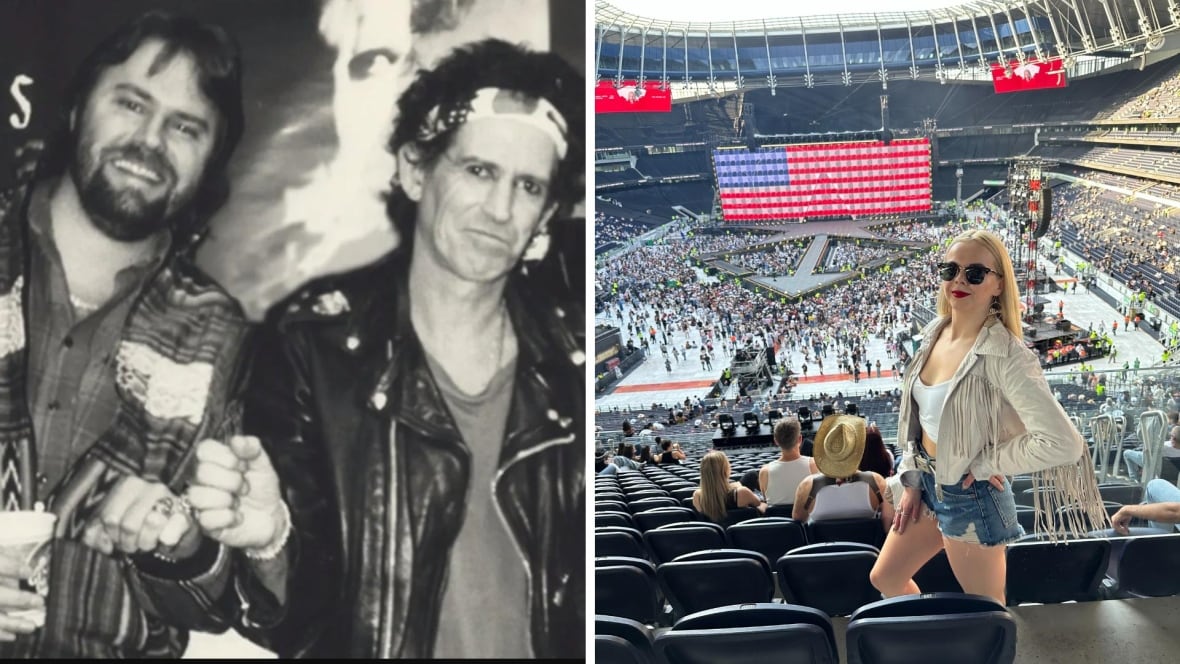

Jessica Lam saw Swift’s Eras Tour in Seattle, Vancouver and London. She still remembers how it felt to see the pop star on stage for the first time.

“My tears were falling,” said Lam. “Being in-person in the stadium, experiencing it with your own eyes — it’s so different.”

This year has also seen a slate of massive shows, with major concerts still on the way — including the highly anticipated Oasis reunion, set to play two sold-out shows at Toronto’s Rogers Stadium.

Why do people attend stadium concerts?

For music journalist and author Steve Newton, who grew up in B.C. in the 1970s, the draw of stadium shows is all about the spectacle. He recalls attending massive concerts at the 54,500-seat BC Place stadium, with his first big show being The Jacksons in 1984.

There, Newton described seeing a seven-story stage constructed by 240 workers, and an opening act involving “four computer-controlled camel-like monsters.” Michael Jackson performed a vanishing act, placed into a silver box by two giant spiders, lifted into the air, and blown up — only to reappear moments later on a platform stage left.

Newton has also seen Pink Floyd with their “amazing lights and lasers,” AC/DC’s 1988 show where Angus Young leaped out of a “missile-shaped device” and the Rolling Stones in 1994, featuring massive inflatable figures like a guitar-playing Elvis and a “punk baby.”

Agne Jotautaite, a senior IT product manager in Lithuania, has turned concert-going into a serious hobby. She estimates she’s attended about 100 shows including Imagine Dragons, Coldplay and Beyoncé.

“You’re in the stadium of like 50,000 or 60,000 people singing one song all together, and it just gives you such a strong sense of belonging [and] unity,” she said. “There is hope [that] people can stay in peace, and just enjoy and have a good time.”

What has changed?

In his academic work, Waksman studies the mechanics behind producing live music on a massive scale, especially the evolution of technology that makes modern stadium concerts possible.

At Shea Stadium in 1965, The Beatles played through the venue’s house-built PA system which was designed for baseball announcements and organ interludes. That setup was “woefully inadequate” for a concert, Waksman said.

The stadium sound experience evolved over the decades into one that surrounds the audience, rather than “throwing a huge amount of sound at you from the front of the stage forward,” he said.

According to Waskman, real innovation in stadium concert production began in the 1990s. U2, in particular, led the charge with their PopMart tour, which used immersive multimedia and stage design to “make the audience feel closer to a very large scale experience, both visually and sonically.”

And while the sound and visuals evolved, so did the business model.

Music journalist Nick Krewen says that as record and album sales dwindled thanks to the rise of music streaming services, artists now depend on concert and merchandise sales — which has led to rising ticket prices.

For the fans

Despite the shifts in technology and economics, Krewen says one thing hasn’t changed.

“I think that artists are always really touched when people love their music and they want to reward them for that,” he said.

“So if you can gather and grow your fan base to the point where you know that you can fill stadiums, that’s really why you’re doing it.”

Lam felt that connection during Swift’s Eras Tour, who performed songs that spanned her nearly 20-year career.

“The songs that she picked as part of the main set list was just perfection,” said Lam. “Your emotions are definitely going up and down.”

For fans like Bova, who witnessed the heights of Beatlemania in Shea Stadium 60 years ago, those emotions can last a lifetime.

“There have been many events that have changed most of our lives — good, bad, terrible, great,” said Bova.

“But this is one thing to go back to and just relive and remember.”