Listen to this article

Estimated 4 minutes

The audio version of this article is generated by text-to-speech, a technology based on artificial intelligence.

In July 1940, as war raged in Europe, a British naval vessel docked quietly in Halifax harbour.

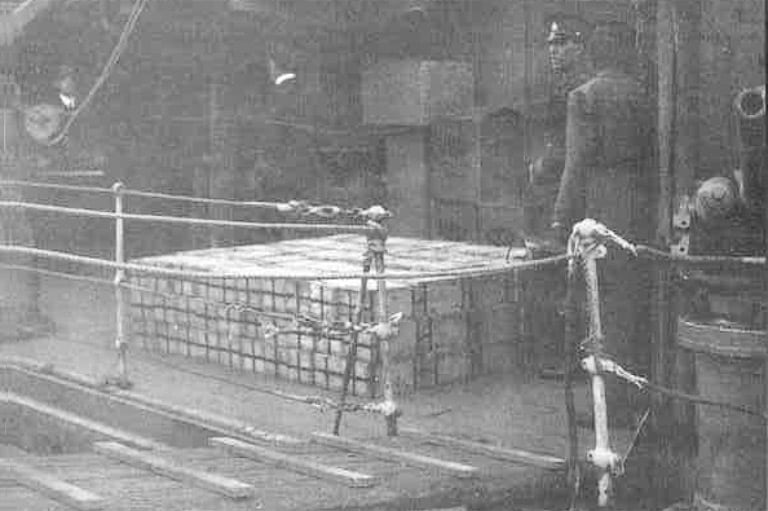

The cargo was labelled as fish but was, in fact, gold and securities.

The ship was HMS Emerald, and it carried the first in a series of shipments transporting Britain’s wealth to safety in Canada.

It was part of Operation Fish, a secret mission that would see Halifax play a key role in ensuring Britain’s success in the Second World War.

By then, the Atlantic Ocean had already become a graveyard for hundreds of Allied ships thanks to Germany’s formidable U-boat fleet.

But while the Germans sank hundreds of other vessels that year, all of the Operation Fish ships made it to Halifax safely.

In total, the 2025 equivalent of over $200 billion in gold and securities came through the port of Halifax.

It remains the largest movement of physical wealth in history.

When the gold and securities arrived in Halifax, they were inspected by officials from the Bank of Canada and loaded onto waiting Canadian National Express train cars.

Escorted by hundreds of armed guards, the assets headed to Montreal before eventually making their way to the Bank of Canada vaults in Ottawa.

“Winston Churchill had just become prime minister at a perilous time,” notes Paul Doerr, a professor of history at Acadia University.

Churchill had made it clear in his speeches that the British Isles could be overcome militarily by the Nazis.

“He expected that if the work continued, it would be continued by the Empire countries, the Commonwealth, including of course Canada,” Doerr said.

“That’s why the gold reserves moved out, to enable those countries to carry on the war, to finance the war.”

The gold and securities that the British government held were considerable.

Doerr noted that the Emergency Powers (Defence) Act 1939 allowed the government to compel citizens to sell or hand over their foreign securities in exchange for British currency.

This was the mechanism used to gather the billions of dollars in foreign assets that were shipped to Canada in Operation Fish.

In addition to saving it from the Nazis, the wealth was also needed on the other side of the Atlantic to purchase American armaments.

The United States was not yet in the war, and although Churchill had an ally in President Franklin Roosevelt, the isolationist movement was very strong, Doerr said.

The Americans’ cash-and-carry policy required immediate payment in gold or US dollars for American-made war materials, which Allied nations then had to transport on their own ships.

Having its wealth in Canada meant that Britain could access and sell assets to meet this U.S. requirement and continue funding the war effort.

Although the transfer was successful and necessary, Britain’s resources were nearly exhausted by the end of 1940.

As author Alfred Draper notes in his 1979 book about the operation, a desperate Churchill wrote to Roosevelt: “We shall go on paying dollars as long as we can, but I should like to feel reasonably sure that when we cannot pay any more you will give us the stuff all the same.”

When Britain’s wealth ran out, Roosevelt replaced cash-and-carry with a lend-lease arrangement, sustaining the Allied war effort.

Operation Fish bought Britain the time it badly needed to survive.

Halifax, serving as the trusted gateway for a desperate government, played a silent but indispensable role.

It secured the war chest that funded the pivotal fight against the Nazis, saving not only Britain’s economy but perhaps the entire Allied cause.

MORE TOP STORIES