It’s not easy to have sex when you’re a couple of slippery, limbless fish in the ocean.

But the ratfish has a workaround. The male has a unique, club-shaped appendage on its forehead, called a tenaculum, which it uses to cling to the female’s pectoral fin while mating.

Some scientists thought these appendages were lined with the same hard, spiny scales that cover the bodies of the ratfish’s distant cousins, sharks and rays. Not so, according to new research.

“No, they’re totally teeth,” Karly Cohen, marine biologist at the University of Washington, told As It Happens host Nil Koksal. “Just like the teeth in your mouth or your cat’s mouth or in the ratfish’s mouth.”

The findings, published last week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shed new light on the deepsea creatures, while upending the long-held assumption in evolutionary biology that teeth grow exclusively in mouths.

“It highlights the flexibility of something that we think is so core about vertebrates and animals,” Cohen said. “It’s cool to see something that’s so important — teeth — pop up in this really interesting way.”

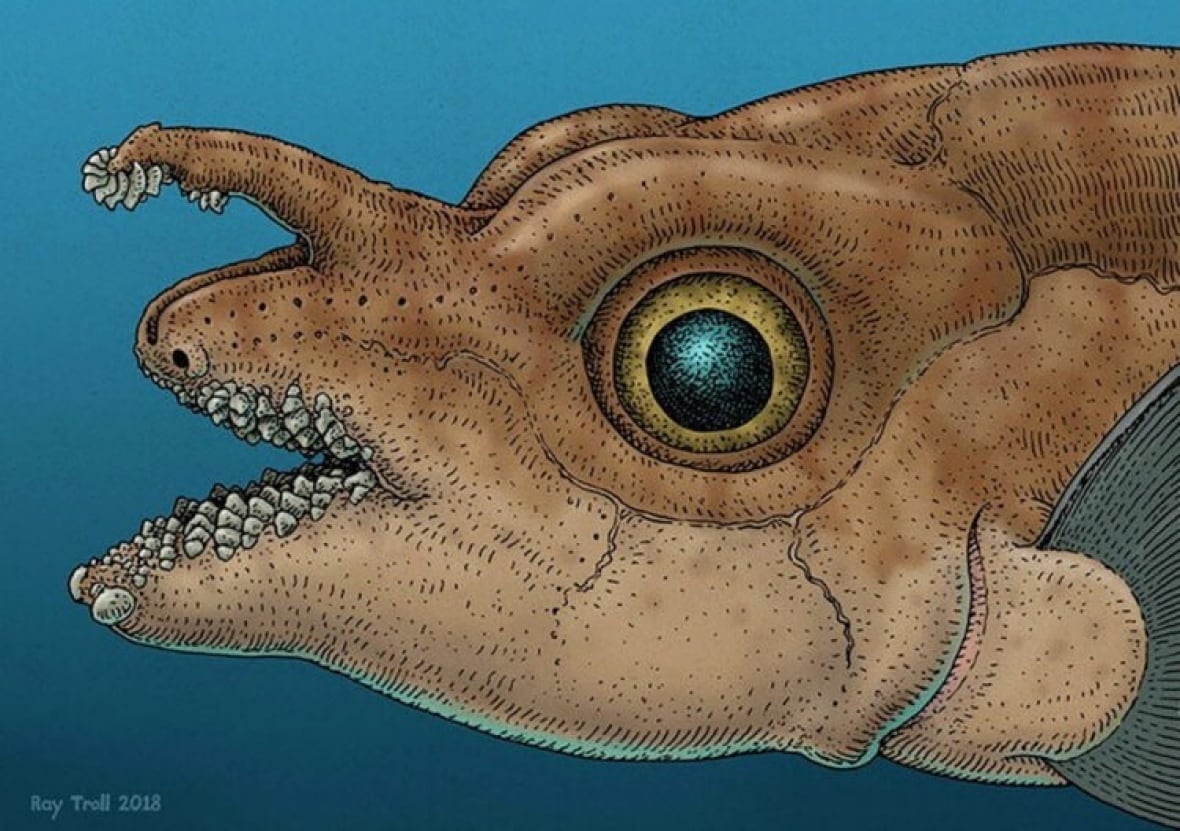

Ratfish are deepsea dwellers that can reach up to 60 centimetres in length. They belong to a category of cartilaginous fish called chimaeras, which split off on the evolutionary tree from sharks about two million years ago.

They are sometimes also called ghost sharks or spookfish because of their shimmering bodies and big bright eyes that appear to glow green in the light.

“I think that they’re beautiful,” Cohen said.

For this study, Cohen and her colleagues worked with spotted ratfish, a species with a venomous dorsal spine that’s abundant in the waters of Puget Sound off the coast of Washington state.

The team observed spotted ratfish in the wild, and then caught and analyzed 40 specimens using micro-CT scans.

Inside the tenaculum, they found found rows upon rows of shark-like teeth. They were all embedded inside a band of tissue called the dental lamina that, before now, has only ever before been documented in an animal’s jaw. Tissue samples of the tenaculum revealed genes associated with the formation of teeth in vertebrates.

Aaron LeBlanc, a King’s College London paleontologist who studies the evolution and formation of teeth, says he’s never seen anything like it.

“It’s just strange,” LeBlanc, who was not involved in the research, told CBC.

LeBlanc says he was skeptical at first about the study’s conclusions, as he would have thought the tenaculum was full of denticles — the tooth-like scales that are present on sharks and rays. But he says the researchers “did a really good job of characterizing them and showing that they developed exactly the same way that teeth do.”

“That just goes to show that there’s lots of other unique things to discover out there — especially when it comes to teeth,” he said.

But why, though?

Cohen says there’s still plenty to discover when it comes to the ratfish’s surprising forehead teeth. How and why did they evolve that way? Were they always meant for sex, or did they start out as a defensive mechanism that evolved and changed over time?

They found some clues, but not enough to paint a full picture.

They examined fossil records for Helodus simplex, a prehistoric chimaera that lived more than 300 million years ago, and found evidence of a toothy tenaculum-like appendage emerging from the top if its nose and extending over its upper jaw.

What’s more, researchers discovered that female spotted ratfish have small, pimple-like structures on their foreheads, just like juvenile males. But unlike the males, their little humps never sprout into a full tenaculum.

“I’m not exactly sure why the females retain the ability to grow them, or have the ability, or what they’re using it for,” Cohen said. “It would be awesome to find out more.”

Holy moly, isn’t nature fabuloso?– Milton Love, marine biologist

Milton Love, a marine biologist at University of California’s Marine Science Institute in Santa Barbara, says he’s not surprised the ratfish use their forehead teeth to latch on during sex.

Many species of male sharks will bite down on the female’s thick neck skin during mating for the same purpose, says Love, who was not involved in the study.

“It’s not terribly surprising, but it’s just charming,” Love said. “With these kind of stories, you wind up going, like, ‘Holy moly, isn’t nature fabuloso?'”