Welcome to our weekly newsletter where we highlight environmental trends and solutions that are moving us to a more sustainable world.

Hi, it’s Anand. I’m talking about death again because a reader mentioned medical implants as one potential barrier to a truly green burial. So, I looked into two alternatives.

This week:

- Liquified, composted: How green are these alternative death practices?

- The Big Picture: Floating solar stands up tall

- Waste pickers want deposits back on more materials — and it’s not just about the money

Liquified, composted: How green are these alternative death practices?

For more than 20 years, Sam Sieber’s family has been in the business of Aquamation, their trademark for using mostly water to rapidly break down a body without emitting carbon into the air.

“We thought this was a huge environmental pull and the number one reason families would choose it,” explained Sieber, Chief Strategy Officer for Bio-Response Solutions.

“We were wrong, it’s not.”

Turns out, as Sieber talked to more families, choosing Aquamation was more about finding an alternative to flame cremation.

“We hear stories, ‘Dad always loved water, every summer on the lake.’ So sometimes there’s a draw to the water,” Sieber told CBC News from Danville, Ind. “And then we’re also finding probably the biggest reason is people just perceive it to be more gentle.”

Gentle isn’t the first word that comes to mind when looking at the industrial steel drum that’s used in the process, formally known as alkaline hydrolysis. Inside, water — along with heat, pressure and chemicals to make that solution alkaline — circulates around the body, speeding up its breakdown and leaving only the bones behind, in a matter of hours.

The results, say its proponents, are less energy use (temperatures are 90 to 150 C compared to flame cremation’s 750 to 1000 C), more solid remains (the process boasts 20 to 30 per cent more ashes than flame cremation’s estimated ~2 kgs) and no airborne emissions — the liquid remains are sent to wastewater treatment.

Sieber adds that surgical devices and implants like titanium hips are recoverable, and won’t be left in the earth, unlike traditional burial and even some other green death practices.

“We aren’t burying those precious metals forever. They [can] go to a recycler and ultimately are reused,” Sieber said.

It’s not clear how many alkaline hydrolysis procedures have been carried out in Canada, though it has been available in several provinces for more than a decade, including Saskatchewan, Quebec and Ontario — with Manitoba just recently starting to offer it. People can pay $1,000–2,000 for the process alone. Notably, Archbishop Desmond Tutu chose alkaline hydrolysis in 2022, for its environmental benefit.

This method has been used for decades to dispose of pets, livestock and lab animals, in some cases to avoid infectious pathogens surviving burial. Another emerging environmental option has the same roots.

“Obviously, if you can compost a cow, you can compost a human being,” said Katrina Spade, CEO of Recompose, a company whose service is legal in 14 U.S. states, but not yet in Canada. She jokes it’s a “sustainable, Prius-driving cousin” of cremation.

“We’re placing a body along with a bunch of plant material into a vessel,” Spade explained. Wood chips, straw and alfalfa are put into a machine with the body. With heat and occasional rotation, it yields on average, a cubic yard of soil in a matter of months.

This can also allow for recovery of medical implants. While Recompose also claims to use less energy and not emit your body’s carbon through burning — the draw, once again, isn’t entirely environmental.

“I think when people are choosing this option, it’s because it feels personally meaningful to them,” Spade told CBC News from Seattle, saying clients want a connection to the soil.

“It’s a profound idea … that those molecules will truly and literally become part of that tree, that forest, that grove.”

Environmental impact

Juliette O’Keeffe, senior scientist at the National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health, recently reviewed the environmental impacts of alternative death practices, including alkaline hydrolysis and human composting.

With the former, she says liquid remains could present a hazard to sewage infrastructure and the environment if not properly handled. In Ontario, businesses that provide alkaline hydrolysis are required by the regulator to follow municipal sewer bylaws.

With human composting, the concern is also with the leftover material, as it may contain infectious disease or chemicals present at the time of death.

“Some of them will be broken down. Some of them can be degraded, but we don’t have any research, really,” O’Keeffe said. Recompose says the heat in their process kills most pathogens, but does list a few rare infectious diseases that disqualify individuals from participating, including Ebola and the neurodegenerative disorder Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Ultimately, these are not widely adopted death practices, compared to conventional burial and cremation. Still, both these methods show the allure is about alternatives.

“It’’s a general move towards more environmentally sustainable practices and thinking about your environmental impact after you’ve left the Earth,” O’Keeffe said.

— Anand Ram

Old issues of What on Earth? are here. The CBC News climate page is here.

Check out our podcast and radio show. In our newest episode: Wasted food has a climate cost bigger than the aviation industry. So how can we toss less – and feed hungry people at the same time? We meet someone who’s made it a mission to eat everything she buys, including scraps you might not have ever considered saving for later. Then, we head out with a charity that collects leftover food from grocery stores and passes it along to people in need. And, we hear what’s needed for Canada to meet its promise to cut food waste in half by 2030.

What On Earth28:02A doggy bag of ice cream and other adventures in saving food

What On Earth drops new podcast episodes every Wednesday and Saturday. You can find them on your favourite podcast app or on demand at CBC Listen. The radio show airs Sundays at 11 a.m., 11:30 a.m. in Newfoundland and Labrador.

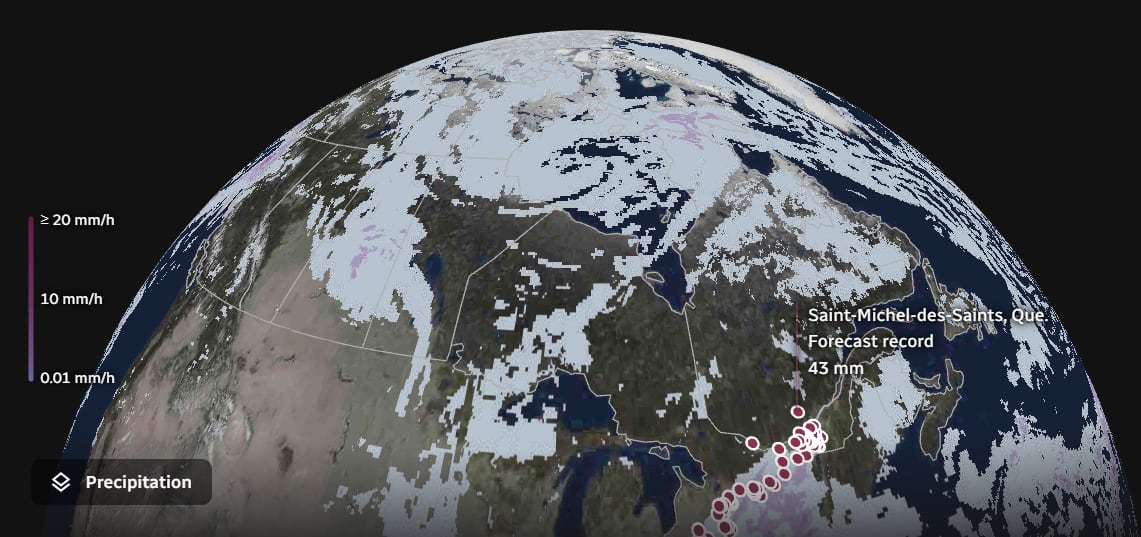

Check the CBC News Climate Dashboard for live updates on rainfall records across the country. Set your location for information on air quality and to find out how today’s temperatures compare to historical trends.

Reader feedback

Last week, Inayat Singh wrote about Toronto’s looming waste crisis: how it was running out of space at its main landfill, and considering incineration or energy-from-waste as a possible solution. Dealing with garbage and its associated social and environmental impacts are a big issue for many people, and we saw many of you write in with your thoughts.

Richard MacIntosh, like several other readers, was critical of using landfills and wrote, “Garbage is a natural resource that humans should be using for energy and heat, it’s a good use of that natural resource — humans create garbage.”

Bill Spiller shared a link with more information about the Spittelau incinerator in Vienna, which has received design acclaim. Spiller wrote, “When I visited it, while living in Vienna, I could see no resemblance to an Incinerator but rather à modernistic cathedral. And the grounds around it were spotless and litter-free.”

Write us at [email protected] (and send photos there too!)

The Big Picture: Floating solar stands up tall

A floating solar farm billed as the first with vertically mounted panels was officially completed this month at the Jais gravel pit in Bavaria, Germany, says KBE, the company that provided the cables for the project. The system includes 2,500 solar panels with a total area of 13,000 square metres and a maximum output of 1.8 megawatts (MW), says Sinn Power, the company that built it. But their vertical profile means they cover less than five per cent of the lake surface (the maximum under German law is 15 per cent). The company says this makes the technology suitable for smaller lakes. The panels face east-west and are designed to generate the most power earlier in the morning and later in the afternoon when traditionally mounted panels do not. Sinn Power says this makes them “grid-friendly” and allows them to potentially generate more revenue selling power when supply is lower.

— Emily Chung

Hot and bothered: Provocative ideas from around the web

- The costs of geothermal energy projects are dropping, according to Canadian start-up Eavor, which is close to bringing its German project online. It has adapted techniques from the oil and gas industry with the aim to provide electricity and heat almost anywhere in the world.

Waste pickers want deposits back on more materials — and it’s not just about the money

In the push to divert more waste from landfills, people known as binners — who scour cities for often discarded redeemable materials — could hold part of the solution.

Collecting cans or bottles for their 10 cent deposit keeps waste from ending up in the wrong place and provides wages for those who return them.

Now, waste pickers or binners say the important work they do should be afforded a bigger role.

“I think there’s room to innovate and to grow … to find other items that could be collected and taken out of the landfill,” said Sean Miles, director of the Binners’ Project, a collective of waste pickers in Vancouver trying to improve economic opportunities and reduce stigma over the practice.

Miles made the comments from an annual Vancouver event where, through government grants and private sponsors, the Binners’ Project hands out thousands of dollars to people who bring disposable, single-use coffee cups to a downtown park.

It’s done to show the collective ability of waste pickers to manage items that often end up as trash or litter when they can be recycled, if they have value for the collector.

Over twelve years, the event has amassed more than 700,000 cups, which can be placed in residential blue boxes for recycling in places like Vancouver, but often end up in the trash or as litter.

This year, the Binners’ Project handed out more than $21,000 — a record amount — to people who participated in the event, like Erica George who earns wages through bottle and can returns.

“I missed last year, so I wanted to make sure I got here this year,” she said. “I just follow my feet.”

Collecting cans or bottles to return for the deposit is a way to reduce garbage, but it’s also a way for many to make money. Waste pickers, or binners, say the important work they do should be afforded a bigger role. As Chad Pawson reports, they want deposits assigned to other types of waste.

At the coffee cup event this year, there were representatives from waste picker organizations across Canada and U.S. who shared best practices and advocated for progressive public policy that would enhance the work.

“If you didn’t have waste pickers, we’d be swimming in plastic,” said Barbra Weber, a local waste-picker organizer from Portland, Ore., who is also on the executive of the International Alliance of Waste Pickers.

“The most important impact that we have is environmentally.”

B.C.’s provincial government is looking at ways to reduce waste this way. Three years ago, it added milk containers to the current deposit system, estimating it would result in 20 to 40 million more milk containers being recycled annually.

It’s currently trying to figure out how to manage waste from things like batteries, mattresses, camping fuel canisters, fire extinguishers, medical sharps and electronics as part of its extended producer responsibility five-year plan.

As for coffee cups, the Ministry of Environment said in a statement it is looking at how to reduce their waste and is “considering policy approaches that will improve the prevention and recycling of non-residential packaging waste in communities across B.C.”

It said ministry staff will be meeting with the Binners’ Project in the coming weeks to discuss the circular economy and non-residential waste.

She said there are more than 40 million recognized waste pickers around the world who have the ability to vastly influence the way waste is collected and kept from harming the environment.

“I think that everything should have a redeemable value,” she said, listing off items like single-use plastic, cigarette butts, electronic waste and single-use coffee cups.

“If it had a value, I think [waste pickers] would be getting more of it before it gets to a place we don’t want it.”

George agreed.

“Oh hell yeah, I would probably collect them then,” she said, adding that materials just have to be items she can reasonably collect, carry and redeem.

Jutta Gutberlet, a University of Victoria geography professor who studies waste governance and is working to bring a program to the school that could empower waste pickers, says the expansion of materials with deposits could greatly help pickers and waste diversion.

“They could make sure the materials then really go into the right waste streams and of course it would support their livelihoods.”

She cautions though that any new policy about deposits needs to factor in the abilities and limits of waste pickers.

For example, she says milk containers, which have the same deposit value as an aluminum can but take up much more space, are often passed over by binners.

“Because they are so voluminous, the diverters don’t really like to collect them because they take up all that space and only give a fraction back to them.”

— Chad Pawson, with files from Dominique Levesque

Thanks for reading. If you have questions, criticisms or story tips, please send them to [email protected].

What on Earth? comes straight to your inbox every Thursday.

Editors: Emily Chung and Hannah Hoag | Logo design: Sködt McNalty