Jonathan Wener has spent 50 years scouring the art world for the lost paintings of his great-great-grandfather, William Raphael.

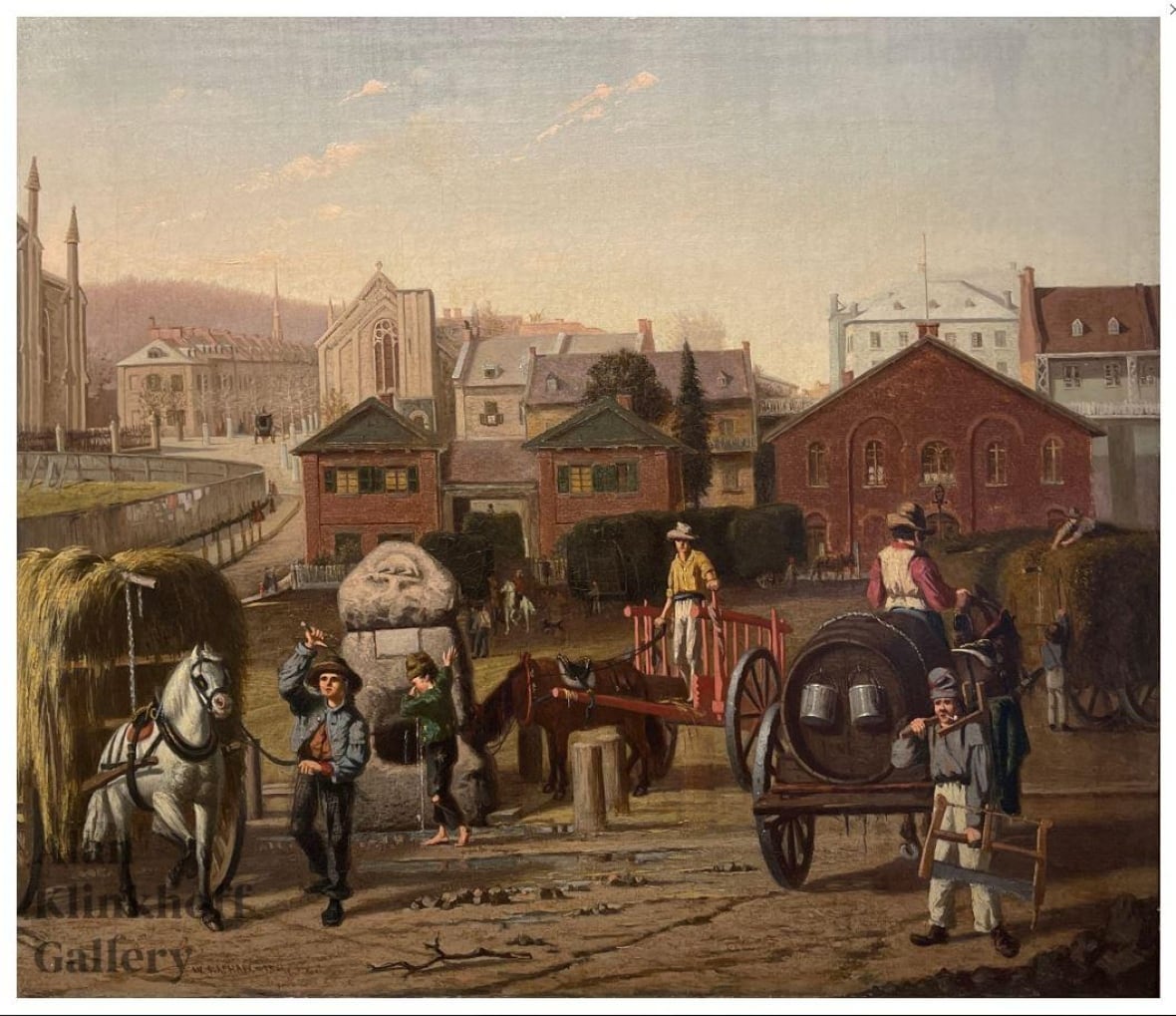

The 19th-century Montreal painter is best known for his portraits of les habitants — French settlers who worked the land — offering little windows into a lost way of life: a woman with a white frilly bonnet washing clothes in a wooden bucket; the Bonsecours Market bustling with shoppers hauling straw baskets against a wintry background.

The scenes are treasured by knowledgeable collectors and art historians alike.

But Wener says his great-great-grandfather never got the public recognition he deserved — and he’s on a mission to bring his work back to the forefront of Canadian art history.

“I think he was cheated,” Wener said.

Sara Angel, an art historian and the executive director of the Art Canada Institute, says Raphael is “one of the few Canadian artists who has given us a record of what life was like in the late 19th century in Canada.”

He is also “the first known Jewish artist in Canada,” she said.

Angel says while his work is part of collections in major museums across Canada, the wider public doesn’t really know him. That’s partly because he never had a major museum exhibit. Another reason is due to prejudice, she says.

“Following the Russian revolution, there was a wave of antisemitism that descended across North America. [Raphael] himself ended up losing his job,” Angel said.

Half a century on the hunt

Wener has spared no effort in his attempts to locate his ancestor’s works.

“I thought I’d only find 20-30 and here we are, every month and every quarter, we are finding more and we find them in strange places,” he said, tracing the finds to Europe and the States.

“I mean, it’s quite crazy,” he said, walking through the hallway in his home where many Raphael paintings hang.

One of his proudest finds is a painting depicting a haymarket in Montreal. Before the time when pictures were prevalent, paintings were one of the only ways to document history.

“We had an art historian research where this was, where the churches were and the [location] … and determined it was Victoria Square, so it’s an interesting piece of Montreal history,” Wener said.

When prestigious art dealer Alan Klinkhoff found that painting, he said it was not titled and the location of the landscape unidentified.

Klinkhoff is one of three generations of gallerists acting as detectives of the art world for Wener.

“Of all the William Raphael’s that I’ve seen available, with the exception of one, that’s the finest Raphael I’ve seen in my career,” Klinkhoff said of the haymarket painting.

“There’s really nothing of that part of Montreal in the visual arts that I’m familiar with that comes close to the calibre of that picture.”

Famous painting auctioned for over $300K

The exception is Raphael’s famous Bonsecours Market painting — a piece Klinkhoff learned was being auctioned in London as part of the eccentric collector Peter Winkworth’s private collection.

Wener had his eye on the piece for years. In fact, it was the painting that sparked his interest in Raphael’s work after he received a copy for his grandmother’s 90th birthday.

So when the iconic painting was auctioned at the popular fine art auction company Christie’s in 2015, Wener stepped out of his birthday dinner and proceeded to engage in a bidding war for the books.

“I watched the bidding go, you know 25, 30, 35, 50, 100 … 300 and I finally said ‘I’m out of this,” Wener said, lifting his arms up in a gesture of surrender.

The painting fetched $324,036 — 10 times more than its estimated value. The buyer ended up being the National Gallery of Canada.

“I went home and said to my wife, ‘I have bad news and good news,'” Wener said. He announced the bad news was he didn’t get the painting.

“The good news is the rest of the paintings are worth much more,” he said, laughing.

100 paintings found in convent

But an auction was not the strangest spot to find a Raphael. Try a convent.

“There was an atelier of William Raphael just beside the altar. In the atelier resided about 100 of his paintings,” Wener said.

He says Raphael had taught some of the nuns at the Congregation of Sisters of Sainte-Anne in Lachine how to paint.

For decades, Wener says he called the convent’s Mother Superior repeatedly offering to buy the paintings, only to be denied. Until one day, after 25 years of pestering, the sisters called to offer him half of their paintings — for the surprising sum of a loonie.

“So I just about fell over,” Wener said, wide-eyed and laughing. Regardless, he says he made a donation to the congregation.

Now with a collection of more than 150 paintings, Wener is ready to share Raphael’s body of work with Canadians.

He says he is thinking about donating a part of his precious collection to a museum, on the condition the work goes up on the walls and not in the archives.

In October, Angel’s Art Canada Institute will release a book on Raphael’s life and work.

“I want him to have his own notoriety and the fame that he’s entitled to,” Wener said.

In the meantime, he remains on the hunt, particularly for sketches of Raphael’s anatomical studies he says he came across and left behind 30 years ago.

“The price might be a little higher but I’d love to get my hands on them,” Wener asserted, sending a message directly to whomever has them.

When asked when he would stop his search, Wener answered with a cheeky smile on his face: “When I’m not breathing.”