Cora Fraser did not go to opening day of harness racing in Woodstock, N.B., where her three-year-old son was fatally injured, but she got to him in time to hold him when he died.

Still not having the final reports on what went wrong that day is adding to her grief, she says.

So is the silence of the groups that organize and run the races.

Fraser, 24, said being a mom was the centre of her life. She had four girls and “baby Gunnar,” whom she described as a hugger and a snuggler who did everything with his whole heart.

On Saturday, June 14, other members of the family had arranged to take the kids to the races and Fraser planned a child-free day with friends at the quarry.

“I don’t drive, so I was waiting for my ride to go swimming,” she said.

What happened next has yet to be spelled out by any of the officials who investigated, starting with the coroner’s office, which has not given Fraser the autopsy report.

The coroner’s office told CBC News that it’s still too early to determine whether an inquest will be ordered and that the case will be assigned to New Brunswick’s Child Death Review Committee for review once all investigations are concluded.

Meanwhile, Fraser replays the video over and over. Races in the Maritimes are broadcast live and posted online.

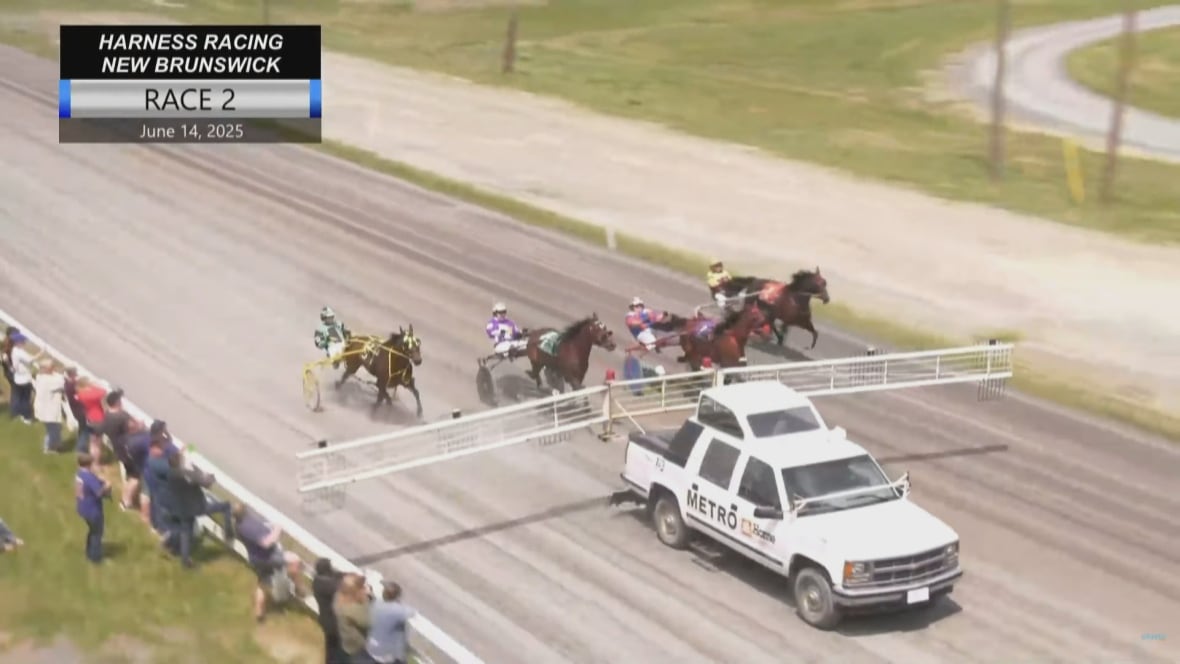

Spectators can be seen lining the track, pressed up against or leaning over the wooden three-rail fence, even as the starting gate sweeps past. That’s where Gunnar was that day, at the start of the second race.

He’s not in view, but the camera shows the starting truck, coming around the bend, its metal gates extended like wings.

The horses — pulling their drivers in two-wheeled carts, or sulkies — are gaining speed as the truck approaches the grandstand, then passes out of view.

Microphones pick up the metallic sound of a crash, then the cries of spectators. The announcer can be heard calling for an ambulance.

Back at home, Fraser’s phone began erupting with messages and calls.

“They said that he was struck and on the ground,” she recalled.

Not daring to wait for a friend or a taxi, and still in her bathing suit and shorts, Fraser started running for town.

“I got pretty far,” she said.

Somewhere near the Grafton Bridge, she was intercepted by a friend, who drove her the rest of the way to the track, although not in time to see Gunnar, who had already been taken away by ambulance.

She said her oldest daughter was screaming and crying.

“I didn’t really need much information to realize how severe it was because of how distraught my oldest was,” said Fraser.

Police have said a child was struck by the starting gate.

Two months later, Fraser now aches to know every detail, including what’s in the police report.

Town of Woodstock won’t release safety review that led to harness races re-starting.

Woodstock’s deputy chief of police said the family will be informed when the office of the Crown prosecutor has finished its review.

“When I mention the Crown prosecutor, people automatically think of charges,” Simon Watts said. “But ultimately this is just for thoroughness.

“We really just want to make sure there is nothing negligent. Because sometimes there could be a criminal negligence aspect, but I’m certainly not saying that’s the case here at all.

“Terrible accidents do happen and that may end up being the final result here — as tragic as it may be.”

Some people familiar with the incident declined to be interviewed by CBC News, saying the whole thing was just an unforeseeable accident and an unfair publicity blow to an industry already hollowed out. Some said they wouldn’t talk because the family has suffered enough.

The Connell Park Raceway — the last of its kind in New Brunswick — opened at its current location in 1968, set high in the rolling highlands of Carleton County.

The land and the nearby grounds, assessed at $12 million, are owned by the Town of Woodstock.

The Woodstock Driving Club runs the races at the park.

Horse Racing New Brunswick is the province’s only approved harness racing organization, and the Atlantic Provinces Harness Racing Commission “governs, regulates, and supervises harness racing in all its forms relevant and related to pari-mutuel betting,” according to its website.

Standardbred Canada, a non-profit, promotes harness racing all across the country.

Statements and news releases shortly after the incident expressed sympathy, but Fraser believes someone owes her more than their condolences.

She wants to see the safety review, its recommendations, and the steps taken to prevent a similar death.

When Fraser reached the hospital, medical staff explained they wanted to get Gunnar into the CAT scan but were having trouble getting him stabilized. She said he was intubated, his neck was in a brace, and his head was wrapped in gauze. She said a nurse was performing CPR.

“And the doctor very faintly from the corner of the room explained kindly that the only thing that was keeping him alive was the nurse pumping his heart for him,” Fraser said.

“So I made the decision I felt was appropriate and I told them to, you know, hands off, and we held him and we kissed him.”

A memorial service was held in Hartland on June 21.

Maddie Walton, who describes herself as a chosen sister to Fraser, spoke at the funeral.

She said Gunnar had a spark in his eyes and mischief in his smirk. He loved trains, trucks and superheroes and helping out his mother.

He loved jokes, she said, and making people laugh.

“And every time, you were rewarded with that magical from-the-belly chuckle.”

She said Gunnar was bold, hilarious, kind, wild, soft, strong, and endlessly sweet.

WorksSafeNB expressed condolences but said it had no role, because it was not considered “a workplace health and safety matter.”

However, the work of putting on the races did continue that day.

“They didn’t even stop,” Fraser said.

It’s not clear when news of Gunnar’s death got back to the park.

In a statement issued June 17, Woodstock Mayor Trina Jones said: “We are committed to working with our event partners to support them through this process. At the same time, we must ensure that due diligence is done to protect the public and prevent future accidents.

“As for harness racing, we have advised both [Horse Racing NB] and the Woodstock Driving Club that there will be no harness races allowed until we complete the full safety review.”

On July 22, a statement from Mitch Downey, a veterinarian and president of the provincial organization, was published on the Standardbred Canada website.

“We are hopeful that our letter and supporting documentation from earlier today will convince the Town Council that we have done our part as requested by the [harness racing commission] in their safety recommendations. Friday night (August 1) Old Home Week racing is critical to the Woodstock Driving Club and HRNB.”

On July 24, at what was described as a special meeting, “confidential and privileged information” was shared with town council, leading to a unanimous vote in favour of resuming races after Aug. 3.

“The Town of Woodstock has concluded its formal safety review,” said the town’s news release.

CBC News asked for a copy of the safety review and any information that informed the council’s decision. Those requests were denied and the mayor declined to be interviewed.

“These recommendations from the Commission have not yet been released to the public by the Commission, so we are not able to comment further on the specifics, other than to note that they have been satisfied and the Commission sanctioned the resumption of racing,” the town clerk wrote in response to further inquiries.

CBC News made multiple attempts to speak to Downey and to Kyle Burton, director of racing with the commission. Neither responded to requests for interviews.

The Woodstock driving club also declined an interview.

Multiple requests to speak to Darryl Kaplan, president and CEO of Standardbred Canada, also went unanswered.

When asked about future changes to the track, the mayor answered by email.

Jones said the town is now looking at what it would cost to replace the entire perimeter fence. Thus far, a new fence built five feet high would cost about $75,000. Rebuilding to a height of eight feet would cost about $30,000 more.

When racing resumed Aug. 4, the length of wooden fence that runs along the home stretch and below the grandstand had been reinforced by a second metal fence affixed with signs to stay off the fence.

Similar signs have also gone up at tracks in Charlottetown and Truro.

Still, spectators can’t seem to resist leaning on or over the fences, even as the starting gates pass by.

A quick viewing of streamed races on YouTube shows it happening this month at raceways in the Maritimes, Alberta, Manitoba and Ontario.

Ross MacDonald, a veteran of the harness racing scene in Saint John long before it closed in 2022, said the industry poses no threat to the people who watch.

MacDonald said it’s true that drivers like him have been hurt and even killed.

“Horses fall down,” he said, pointing to where he broke both legs and his shoulder, both wrists and his jaw.

When those injuries sidelined him from racing, he took to driving the starting cars.

He said it really is a two-person job, with a spotter facing backward at the horses, and the driver holding the wheel and keeping the vehicle centred in the track.

On June 14, MacDonald was watching the Woodstock races on his TV.

“When I found out what happened, I felt sorry for everybody,” MacDonald said. “God bless everybody.”

Fraser said she’s been putting up flyers urging people to boycott the Woodstock races because she feels they resumed too soon and without enough transparency. She said the flyers keep being taken down.

She said an adult may know enough to pull back from the fence if they see a gate coming at them, “but Gunnar was just three years old and 11 months,” she said.

“Either this is not a friendly event, or standards need to change,” she said.