We set out to ask what it means to be Albertan — setting up first on a street corner in downtown Calgary. The answers came fast.

“Pioneering.”

“Entrepreneurial.”

“You look after your neighbours.”

After just a couple of hours, the simple version of what it means to be Albertan was pretty clear.

It’s a story about a people who value freedom and take pride in what they’ve built here. People who are more likely to get ‘er done than wait for government to do it.

And here’s what’s interesting. This is all set against the backdrop of separatism — a debate raging with powerful emotions on both sides. One side sees themselves as more Canadian, the other side as more Albertan. But this shared idea of Alberta identity spans the conflict.

Of course, some Albertans in the anti-separatist camp add another descriptor for what it means to be of this province lately.

“Whiners.”

More on that later.

Kevin Bender stopped by with his wife, took a CBC politics questionnaire and described himself as a committed separatist. When asked what it means to be Albertan, he volunteered the word entrepreneurial right away.

“I’m proud to be an Albertan,” he said. “I love the entrepreneurial spirit here. I think we have thrived in a number of ways, but I think that we’re being held back in a lot of ways federally.”

It was the same with Graham Newby, who placed himself in the non-separatist left corner of the political graph.

“Alberta is very entrepreneurial and I come from a family of entrepreneurs,” he said.

“What does it mean to be Alberta … and Canadian, too? I believe it’s both,” he added. “I think it’s a great place to live. It’s a free place to live. It’s a beautiful place to live.”

This summer, we took the data from a major political survey CBC commissioned from Janet Brown Opinion Research, created a large graph of the results and invited Alberta residents to place themselves on it. That helped us understand where participants were coming from when we asked what it means to be Albertan.

It helped us see how often people don’t fit into neat categories. We found many people who said they feel most connected to Canada, also said they’re Albertan to the core — and they draw strength from that.

“I mean it seeps in, this place. If you’re here long enough, it seeps into your subconscious and it seeps into your heart,” said Tamara Lee, a non-separatist, left-leaning retired technical writer who did work for the oil and gas industry. She reached out when we posted a call for these personal reflections online.

Lee grew up watching the Calgary Stampede parade wind by her house each summer, and visiting her cousins in Taber, Alta. Her mom’s family moved there in 1908 to open a Chinese restaurant.

She says she feels Canadian first, in part because of her Chinese-Canadian father who lost his Canadian citizenship during the Chinese Exclusion Act, but still volunteered to fight in the Second World War.

But she feels like she fits in this province; she belongs here.

“I come from a family of entrepreneurs,” she said. “I come from a strong, resilient, independent family and that could not be more Albertan. I feel a connection to the strong, resilient, independent rural people, the farmers and the ranchers and the townspeople.”

She learned about Alberta’s pioneering history from visiting the Glenbow Museum when her daughter was young, and from researching her own century-old house. She feels rooted, she said, and part of a larger whole.

“Every time the wind comes down from those mountains, you’re breathing in Alberta. You really are, and you’re breathing in the history and the culture.… But the wind doesn’t stop at the border, right?”

What defines a culture

As the responses poured in, we heard about Chinook winds, Angus cattle on the prairies, oil rigs, friendly people, a history of treaties and pioneers — we heard all of this. And it might seem unrelated to collective identity, but hold on.

Bloc Québécois leader Yves-François Blanchet ticked off many Albertans recently when he weighed in on the separatism debate. He suggested Alberta would need to have a culture before considering independence.

He said, “I am not certain that oil and gas qualifies to define the culture.”

But work and many other elements shape culture, said Janet Brown, an expert on Alberta culture because of her work polling and running focus groups in this province. Brown joined CBC Radio’s Alberta@Noon for the hour recently partly because of Blanchet’s comments. The question was: What does it mean to be Albertan?

“It’s a little dismissive to say they’re just worried about money. Because how you make your living is a definer of culture, right?” said Brown.

“Through the ages, [work] would define different class structures, it would define different countries. So there is definitely something about the Alberta attitude that is tinged by our industries and the way we make our living.”

It’s also worth noting that Alberta does have a strong sense of itself, she said.

Brown said she grew up in Ontario and lived there for 35 years. Never once did anyone ask her what it meant to be Ontarian.

“I just never used that word, right? But in our surveys and our research and our vernacular, we talk about being Albertan all the time.”

And this on-going debate about separation has a lot to do with identity — how we see ourselves and where we draw the lines around who is part of “us.”

That struggle shows up across the county when pollsters ask people if they feel more attached to Canada or their province, said Brown.

“Ask that question in Quebec, you tend to get a majority of people saying Quebec. You ask that question in any other province other than Alberta and Quebec, you get Canadian.”

“Here in Alberta, [when we asked that question this spring], 34 per cent of Albertans said they feel more attached to Canada than Alberta, 32 per cent more attached to Alberta than Canada and 33 per cent say both equally.”

In the poll, the separatists were more likely to feel attached to Alberta. But there were exceptions. Eighty-nine per cent of committed separatists felt more attached to Alberta. Seventy-one per cent of the left-leaning non-separatists felt more attached to Canada.

What we mean by ‘us’

That identity question seems to be one reason why the debate about separation is so emotional. Talking with people in downtown Calgary this summer, when people identified as Canadian and non-separatist, they often expressed shock that people were trying to divide “us.”

“Us” meant Canada.

For example, we heard this from Himaani Malik, a Calgary resident who has lived in Alberta since 1980: “I think what Alberta is trying to do, or what [Premier] Danielle Smith is trying to do with splitting us up … she’s not trying to be part of the whole.”

(Smith says she doesn’t support separatism, but rather advocates for a sovereign Alberta within Canada.)

And Julie Purcka wrote in to add: “Albertans are whiners; nothing is ever good enough.”

Taxpayers in the province contribute to equalization because we’re doing well, Purcka wrote, but we’re part of Canada and will benefit from their support if the oil and gas industry tanks. She was one of several people who shared that perspective.

But for others “us” means Alberta.

For them, standing up for Alberta and wanting to ensure it’s treated fairly isn’t a selfish impulse from a bunch of “whiners.” Right or wrong, for many the interest in separation is coming from a place of being neighbourly and standing up for the community, for this province.

For example, Alan Brydges is a mine dispatcher who stopped to talk with CBC in a Costco parking lot in Lethbridge. He said his own family is not struggling financially. But he’s toying with the idea of separation because he believes giving Alberta more control over energy development could boost Alberta’s economy and support others in his community.

“It’s sad to see how [the economy and cost of living] is affecting a lot of other families that don’t have dual income. It’s really a struggle for a lot of families that I’m seeing right now.”

Would separation help the Alberta economy? Let’s set aside that question for now. The various opinions on that deserve a separate article.

The point is, he believes separation could help “us” — the community he sees around him.

As we heard from more people, the limits and challenges of identity kept coming up in new ways, constantly redefining what we mean by “us.”

Defining ‘us and them’ in a narrow way

Marla Zapach wrote in to say she identifies first as Canadian because of the 15 years she spent working in conflict zones overseas. But when she moved back to Alberta, she experienced what she sees as a cautionary tale on defining “us” too narrowly — breaking her community into small groups of us and them.

She wrote to us about how common traits in Alberta’s identity can have a sour side.

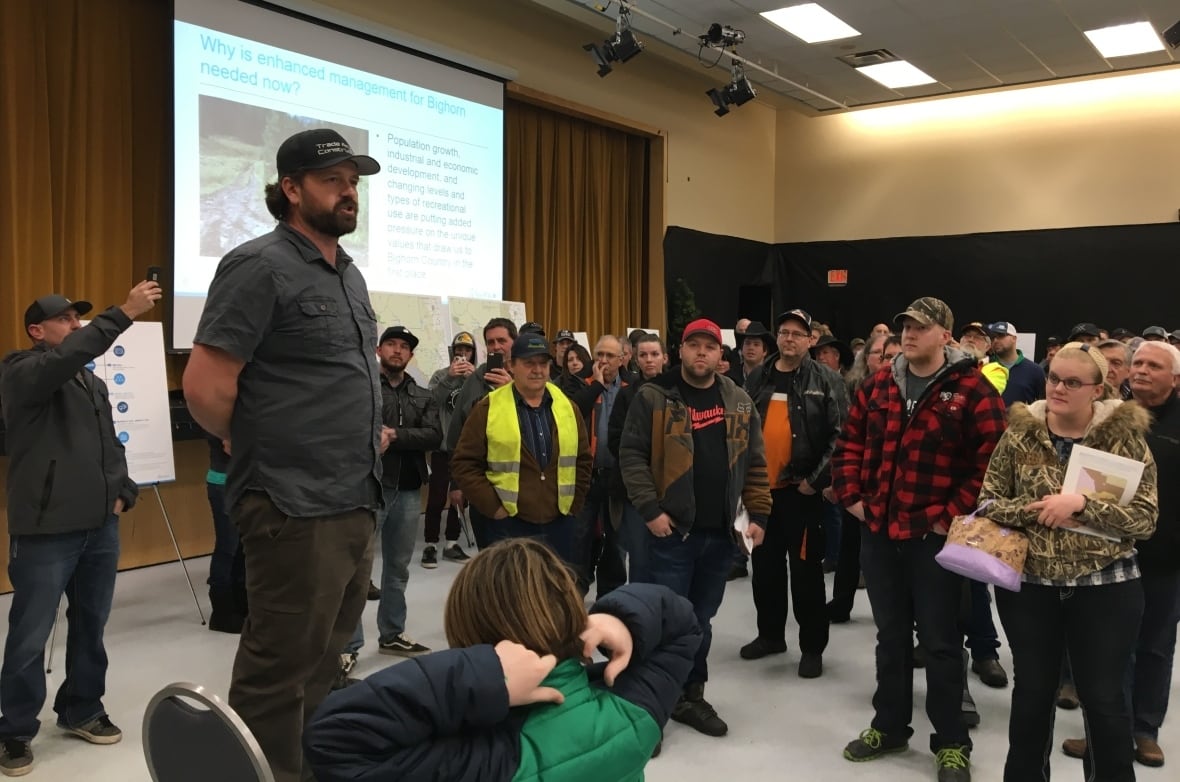

She grew up seeing Albertans as proud, independent mavericks. When she moved back to Canada, she settled in Nordegg, a small mountain town in central Alberta, shortly before the fight around the Bighorn Wildland Park proposal broke out in 2018.

“Many Albertans prioritize the words ‘independent’, ‘entrepreneurial’ or ‘pioneer’ when describing the traits they favour in our population,” Zapach wrote. “What I have witnessed is that these terms underlie a type of selfishness where Albertans dismiss the common good and assume that all resources, especially natural spaces, water, forests, grasslands etc., are for their own use and personal exploitation.”

The fight over the park’s designation pit ATVers against hikers, people with jobs in forestry against environmentalists. Once those internal lines were drawn, it wasn’t a conversation about how to manage land. It was a fight against the other, she said.

“I think perhaps one of the best things for creating unity is our fight against [U.S. President Donald] Trump’s anti-Canada policies. Maybe this will create the common base we so desperately need.”

Others found that Alberta’s identity has been unifying.

East to fit in as a hard-working Albertan

Roger Beebe, 81, lives in Medicine Hat, in the southeast corner of Alberta. When he took CBC’s politics questionnaire online, he ended up in the committed separatist group, which is a change for someone who served in the military and had a 35-year career working as a federal public servant for many years in Ottawa.

Beebe’s American ancestors moved to Alberta to homestead before Confederation. Here in Alberta and in Saskatchewan, where he grew up, his experience of the regional identity felt unifying, he said.

“I grew up … with the Cree, and the Metis, the Germans and Ukrainians, the Polish, Danish and French. We knew everybody had sort of different ethnic backgrounds, but we were just all, we had merged into just all Saskatchewan people, right?”

It was different from the emphasis on multiculturalism and ethnic identities he noticed after moving east to train and work. But that’s not the main reason why he supports the push for separation today. For him, that’s tied to the culture of the federal bureaucracy, where it felt like only Toronto, Montreal and Ottawa mattered.

“It was very difficult to get attention paid to anything outside that, except maybe in the Maritimes. They seemed to have a soft spot for the Maritimes.”

“I’ll give you an example. Say I want to organize a meeting. I would say, ‘Well, let’s go to Saskatoon.’ And people would say, ‘Oh no, no. Let’s go to Cornwall; let’s go to Montreal.’ It was really difficult to get people from Eastern Canada, who were the majority of the government employees, to think about anything in Western Canada. And that started to change my view. A strong central government is maybe not the way to go in a country as big as Canada.”

A strong central government is maybe not the way to go in a country as big as Canada.– Roger Beebe

As far as identity, when he was young, he would have said Canadian first, for sure.

After his career?

“I’m now sitting on the fence. I would say you could put me down as 55 per cent Albertan and 45 per cent Canadian.”

But what about Beebe’s comment on Alberta identity and multiculturalism? Perhaps views on that topic could also have an article on their own.

Rhetoric that’s ‘dividing us’

Salim Bhimji also wrote in with comments touching on ethnicity and Alberta identity. So we called him for a final comment.

Bhimji’s family has roots in India. He moved to Canada 51 years ago, and owned a small photocopy and printing business in Edmonton for decades. He thought of himself as Canadian but found Alberta an easy place to belong and feel accepted.

“Albertans in general are very self-reliant, conservative for the most part and hardworking. That is something that I really admire in Albertans, and for that matter in myself, because I worked hard all my life.”

It was unifying for him.

“If you’re talking about within the community itself, yeah, of course. If you’re in Alberta, everybody’s sort of pulling in the same direction,” he said.

But Bhimji started to question that recently when Premier Danielle Smith’s Alberta Next panels discussed reducing immigration levels or only providing social support to provincially approved immigrants.

“It is this rhetoric that she has jumped on that is dividing us,” he commented.

“You feel that you don’t belong because of the colour of your skin, because of where you came from,” he said. “That makes it difficult … I’m a Canadian but not an Albertan?”

“We don’t need to be separate. We are all Canadian. Yeah, some provinces may get more, some get less, but that’s the nature of our nation. It’s regional.”

These questions around identity likely won’t go away any time soon. After the federal election this spring, Premier Smith made it easier for citizens to bring forward referendum questions, and the Alberta Prosperity Project has a question on separation that’s currently before a judge to see if it’s constitutional.

There’s also a separate petition to reaffirm Alberta’s place in Canada.

Plus, Smith’s Alberta Next panel continues through September. She said she aims to hold a referendum on proposals coming out of that next year.

So what do you think — what does it mean to be Albertan? And how does identity shape this conversation for you and those close to you? Has your connection to this place changed over time?

We’re still listening. Share your thoughts by leaving us a video message, or email [email protected].