Ideas53:59Egg Freezing in an Age of Uncertainty

Toronto lawyer Salima Fakirani was 31 when she decided to freeze her eggs. She had been considering it for a couple of years, and had even gone for a consult at a fertility clinic. But when her employer introduced egg-freezing benefits, she decided to go for it.

She did two rounds of egg freezing and got a “good number” of her eggs into storage.

“I felt like I had bought myself a little bit of time,” she said. “I felt like a weight had been lifted off my shoulders.” She used to joke with her mom that her grandbabies were tucked in a freezer somewhere, so she didn’t have to worry anymore.

Fakirani had first heard about egg freezing from female colleagues at a big Toronto law firm. The idea is that you remove eggs from your ovaries when you’re young and keep them on ice until you need them, reducing the risk that you won’t be able to have kids when you’re finally ready.

The business of egg parties

Egg freezing is seen by some as a way for women to take control of their fertility. Other experts, though, caution that the fertility industry is just profiting off the tension women feel between career building and family building.

Egg cells are hard to freeze and thaw without causing damage. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that a technique known as “vitrification” came onto the scene.

In 2012, egg freezing was deemed no longer “experimental” — and it took off.

Fertility clinics wanted every young woman to know about it. They hosted “egg freezing parties” where young women could sip cocktails and learn about their dwindling egg supplies. They offered free fertility testing. They had catchy ads.

By 2014, a few of the big tech firms had introduced egg freezing benefits as part of their employment package. They believed it would help attract and retain female talent. And many women were interested.

But others felt uneasy.

“What does it actually convey to women when you say that your company will pay for egg freezing?” asks Lucy van de Wiel, a senior lecturer in global health and social medicine at King’s College London in the U.K., and author of a book called Freezing Fertility.

Some people feel it actually discourages reproduction, says van de Wiel: why have a family now when your employer is paying for you to put it off till later?

Unsure about parenthood? Buy more time

Van de Wiel is interested in the business side of fertility. Egg freezing, she says, offers the industry a great growth opportunity. In places where fertility is not covered by public health care schemes, clinics are increasingly controlled by private equity. And for private equity, she says, growth is king.

“It’s not enough to have good revenue, to have good profits,” she says, “you have to show that your numbers of treated patients and of revenue are increasing year on year. And this is where egg freezing comes in, because egg freezing is growing very rapidly.”

In 2013, just 94 Canadians electively froze their eggs, but in 2024, that number was 1,919, according to data from the Canadian Assisted Reproductive Technologies Register. In the U.S. in 2023, more than 39,000 people electively froze their eggs.

Unlike treatments such as in vitro fertilization (IVF), which is for infertile people who want to conceive right away, egg freezing services are aimed at any woman who may want to have children in the future. She doesn’t even have to know she wants kids — she just has to wonder if she does. That’s a lot of potential customers.

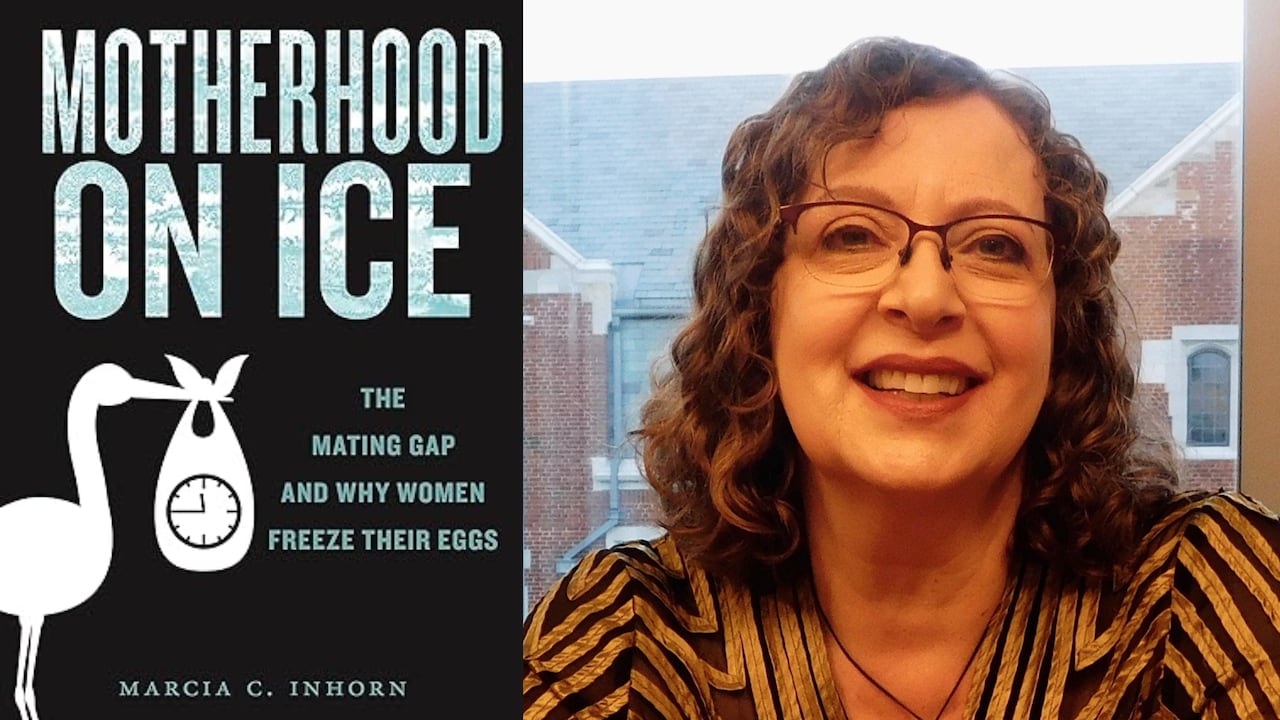

Many people assume women are freezing their eggs so they can put off motherhood and pursue their careers. But Marcia Inhorn, an anthropologist at Yale University who interviewed 150 American women who froze their eggs for her book Motherhood on Ice: The Mating Gap and Why Women Freeze Their Eggs, found otherwise.

The most common reason, she says, was that educated women were having trouble finding men interested in having families with them. Women froze their eggs, says Inhorn, to buy more time while they kept looking.

Many people assume women are freezing their eggs so they can put off motherhood and pursue their careers. But Marcia Inhorn, an anthropologist at Yale University who interviewed 150 American women who froze their eggs for her book Motherhood on Ice: The Mating Gap and Why Women Freeze Their Eggs, found otherwise.

The most common reason, she says, was that educated women were having trouble finding men interested in having families with them. Women froze their eggs, says Inhorn, to buy more time while they kept looking.

Unaware of vital information

Katie Hammond, a law professor at Toronto Metropolitan University who specializes in issues surrounding assisted reproductive technologies, has studied consent documents from Canadian clinics. She has found that people who freeze their eggs aren’t always properly informed by clinics about the risks, the costs, or what using those frozen eggs to have a baby will entail.

Hammond says she has conflicting feelings about the practice. “The optimist in me thinks that elective egg freezing is, to some degree, about reproductive autonomy and giving people the ability to be able to postpone childbearing if they are not in a situation where they are able or wish to have kids in the current moment.

“I think it also gives people who aren’t sure if they want to have kids a little bit of leeway to think about that decision.”

Pessimistically, she says, she sees it as just a for-profit business.

“Employers that offer benefits for it tend to do so in workplace cultures that try and maximize people working as many hours as they can while they’re young.”

Download the IDEAS podcast to listen to this episode.