This is part one of a three-part series from Radio-Canada about the 50th anniversary of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement.

In April 1971, four years before signing the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA), Quebec’s premier Robert Bourassa unveiled his “project of the century” — a plan to harness the huge hydroelectric potential of the province’s northern region as a means to both boost the economy and keep up with growing demand.

The project proposed building 11 hydroelectric dams, including eight on the La Grande river, which stretches from the heart of the province all the way to James Bay, 900 kilometres to the west.

Three other rivers, the Eastmain, Opinaca, and Caniapiscau, would be diverted to fill massive man-made reservoirs, which would submerge 11,500 square-kilometres of forest underwater — about 30 times the size of the Island of Montreal.

The scale of the project is unparalleled in the province’s history, and would take 40 years to complete. Today, it generates 17,000 megawatts of power — half of Quebec’s current production.

Thousands of workers were needed to make that happen. From engineers to cooks, the equivalent of a small village was sent to a remote worksite more than a thousand kilometres away from Montreal as the crow flies. While crews were preparing to build an access road, a crucial step had been overlooked: the province hadn’t consulted with Cree and Inuit communities, whose territory was about to be forever changed by a development project of unprecedented size.

The surprise

Charlie Watt sits with a cup of tea in hand as he stares out the window at the Koksoak River, which flows into Ungava Bay, 50 kilometres to the north. It’s July in Kuujjuaq and the wildflowers have only just begun to bloom — a sign that salmon have returned, according to the longtime Inuit political leader.

As has been a lifelong tradition, soon he’ll head down to the river and retrieve his nets, and hopefully a few fish.

Today, though, the river is much lower than when Watt was growing up, a vestige of it being diverted to feed the James Bay dams, and ultimately, half of the province’s electrical outlets. Nostalgia takes over as he remembers a time he could easily go caribou hunting upriver. But it’s so low now that very few people venture out that way by boat, due to the risk of hitting a shoal and breaking their motor.

Watt also clearly recalls when he’d first noticed the Quebec government’s interest in developing the region and its rivers.

“Prospectors had been around here for quite a number of years, identifying rivers and so on, what potential they have,” he said. “We knew sooner or later this was coming.”

With no community consultation, Watt says he only learned about Bourassa’s “project of the century” by coincidence during a visit to the post office. While waiting around, he scanned the bulletin board and saw a notice about the premier “wanting to develop the economy of the North for the purpose of bringing the electricity down south.”

He said he and many others were shocked to learn about the project and felt it would threaten their traditional way of life.

“Block it, stall it somehow. That’s the response I got,” said Watt.

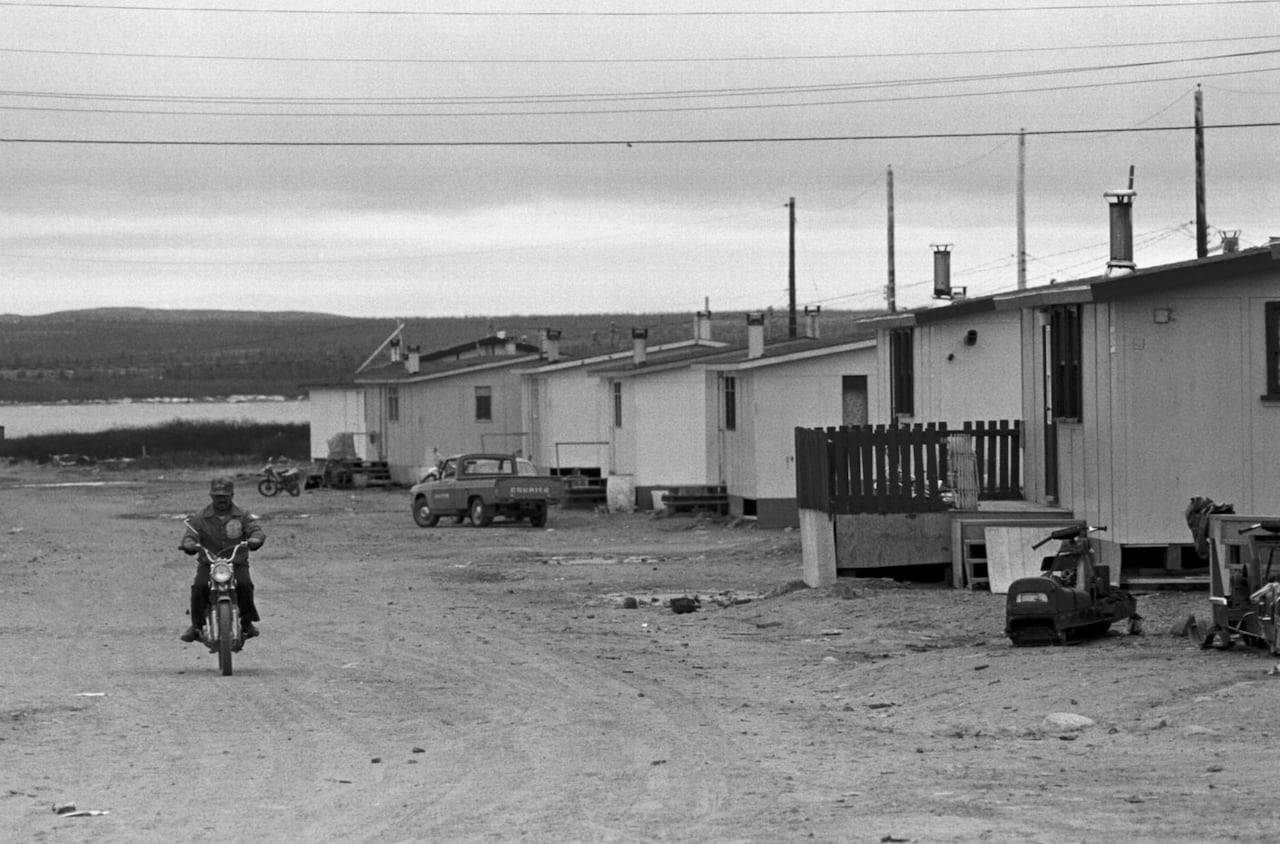

In the early 1970s, there was a deep distrust of authorities among Inuit communities in Northern Quebec. For many Nunavimmiut, the wounds caused by forced settlement — including the slaughtering of sled dogs a few years prior — were still fresh. And a lack of quality government services and support only compounded the issue.

To tell you the truth, we had nothing at the time. We had a little bit of schooling, a hospital, but no nursing stations, and administration being run by the outside, run by Ottawa,– Charlie Watt

The federal government installed rows of small, cramped houses made of plywood in communities, with little regard to the actual residents.

Community members — referred to as “Eskimos” at the time — also had numbered identification tags, or “dog tags” as Watt calls them. “8820 is mine. 8819 was my mother,” he said.

This was the social context in which the province announced its intention to use the region to develop hydroelectricity. Once he finally learned of the project, Watt gathered other Inuit to found the Northern Quebec Inuit Association to ensure local communities would be able to have their say.

A way of life, threatened

The project also prompted backlash in Cree communities around James Bay.

One main point of contention was that the proposed reservoirs would flood traditional trap lines that were still being used by many families.

“When I was out on the land, I never saw anybody from the government out there. So how could they say this is their land?” said Roderick Pachano, former chief of the Cree Nation of Chisasibi, and one of the negotiators of the James Bay agreement.

“What they wanted to do was basically destroy the Cree way of life and the resources, the natural resources that the people depended on for their livelihood […] their food, their medicine, everything that they needed to be out on the land,” he said.

Similar to Watt, Pachano’s first reaction was also to put a stop to the project. The communities turned to Billy Diamond and Robert Kanatewat, two prominent Cree chiefs, to bring their concerns to the attention of the provincial government.

This marked the beginning of a fierce battle for Inuit and Cree people of northern Quebec to reclaim a territory that, for them, was always theirs.

A historic injunction

Charlie Watt says his first meeting with Robert Bourassa left a bad taste in his mouth. It had been some time since the government announced the hydro project when it finally organized a meeting with Inuit and Cree representatives for them to share their concerns.

“[It] didn’t last any more than seven minutes,” said Watt. “We had brought in an [elder] from Kangirsuk and he was not even allowed to say what he wanted to say. The Premier had already made up his mind […] So he only gave us the seven minutes and that’s it, closed the door.”

To Watt, this interaction was the perfect example of the power imbalance between the government and Indigenous groups.

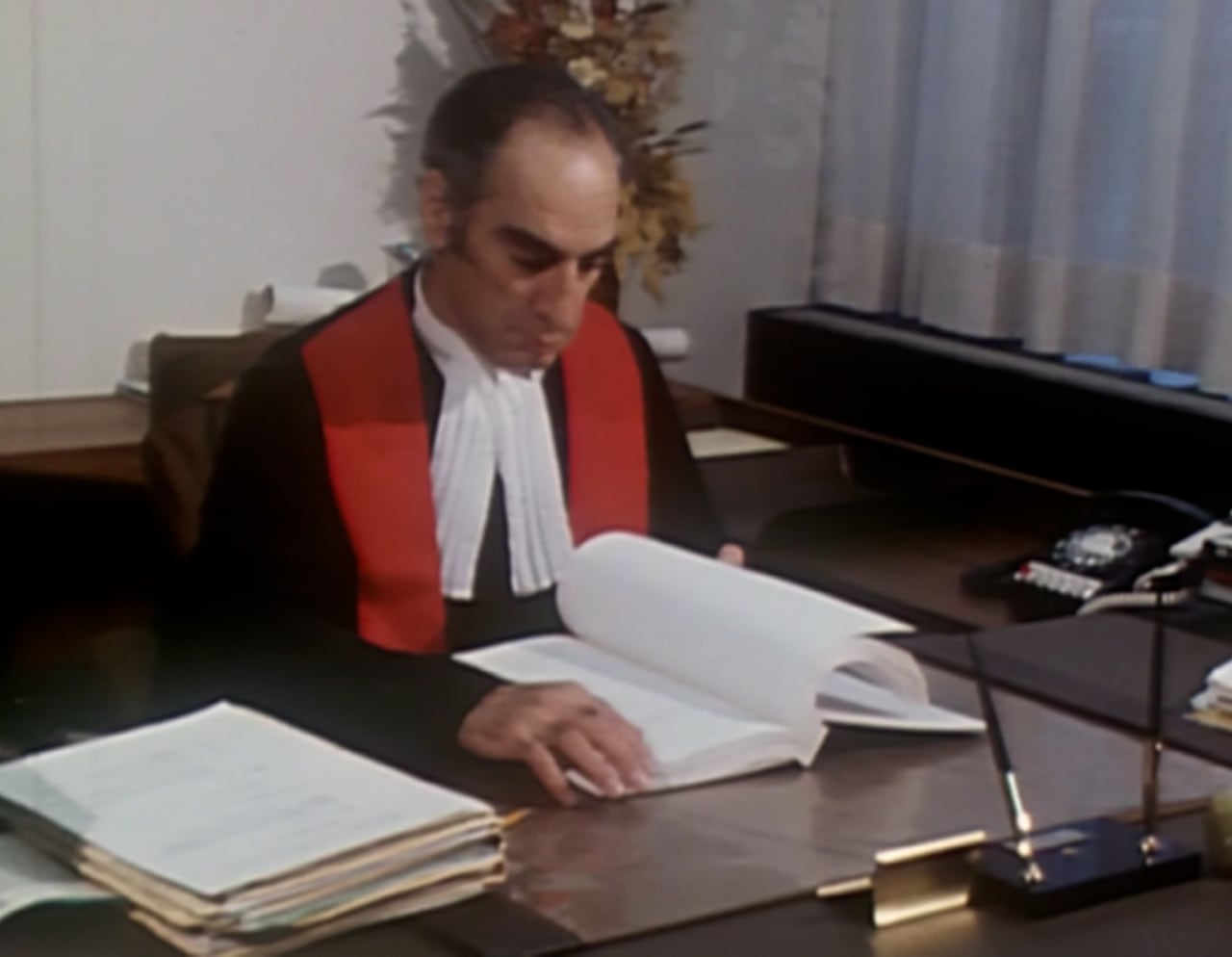

Facing an impasse, Cree and Inuit leaders, along with the Indians of Quebec Association (AIQ), turned to the courts to continue their fight to be heard. In a landmark decision on Nov. 15, 1973, Judge Albert Malouf called for the immediate stop of all construction work and ordered the province to negotiate with Cree and Inuit communities.

Even though the ruling was quickly overturned by the provincial Court of Appeal, Bourassa nevertheless decided to go ahead with negotiations in early 1974.

But the process got off to a rocky start. The AIQ wanted to include demands from all Indigenous groups across the province, which caused tension between the Indigenous parties. Eventually, the organization pulled out of the discussions, and the Cree and Inuit were left to continue on alone.

An unprecedented agreement

Finally, on Nov. 11, 1975, after nearly two years of negotiating, Indigenous leaders signed the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) with provincial and federal governments. The document contains 30 chapters spread over more than 450 pages, which legally outline all hydroelectric, mining and forestry development in the James Bay region and Nunavik.

The second chapter caused a fundamental change for those northern communities, stipulating that Cree and Inuit must forever abandon their rights and claims to the vast majority of their traditional territories.

They’re left with pockets of land near their communities, representing only about 1.3 per cent of the one million square-kilometres included in JBNQA, as well as exclusive hunting and fishing rights to preserve this integral part of their traditional way of life. Quebec now had free rein to build its dams.

In exchange, the federal and provincial governments granted the Cree and Inuit more autonomy over education, health-care, and economic development within their communities —unprecedented concessions in Canadian history.

The Indigenous signatories also received financial compensation totaling $225 million, which they chose to administer through the Grand Council of the Crees, and the Makivvik Corporation for the Inuit.

Roderick Pachano, the former chief and negotiator, says he’s especially proud that the communities have control over the funds.

“I don’t know what our situation would be if we had accepted that the money would be controlled by the government,” he says.

That money has allowed for the creation of several Indigenous businesses, including two airlines, Air Inuit and Air Creebec.

Watt remains ambivalent when looking back on the agreement. To him, it hasn’t resulted in the economic freedom he had hoped for Inuit communities.

The agreement also remains divisive within his region. At the time, leaders in Puvirnituq, Salluit and Ivujivik were fiercely opposed to giving up their rights to the land, and those feelings are still present today.

After signing the agreement, the Indigenous communities of northern Quebec were now faced with the monumental task of actually implementing it. They’d also soon see with their own eyes the impacts the dams would have on the land.