One of Alberta’s most at-risk amphibians is making a comeback.

Provincial efforts to help northern leopard frog numbers bounce back have been successful in establishing new self-sustaining populations, according to the Government of Alberta.

The northern leopard frog, which has been listed as a threatened species in Alberta since 2004, was once relatively common in much of the province. A significant population decline, first noted in the 1970s and 1980s, led to the frog becoming a focus of conservation campaigns.

Brett Boukall, species at risk wildlife biologist with the province, said reintroduction efforts have centred around translocating the frogs, or releasing eggs into new areas to create new populations.

“When its translocation efforts were first put in place, the population of northern leopard frogs in the province wasn’t looking so good,” he said.

“Since then, we’ve been able to determine a wider distribution and a greater number of populations spread across the southern portion of the province.”

Reintroduction was successful at Battle River, Kinbrook Island Provincial Park, Beauvais Lake Provincial Park, Grainger, and Wyndham-Carseland Provincial Park, with biologists confirming the presence of self-sustaining northern leopard frog populations in those places.

“Translocating eggs proved to be quite successful in being able to establish new populations of northern leopard frogs at different reaches within their former range,” said Boukall.

The successful frog reintroductions, coupled with existing northern leopard frog populations naturally found in other parts of Alberta, mean the province won’t need to introduce more populations for the time being.

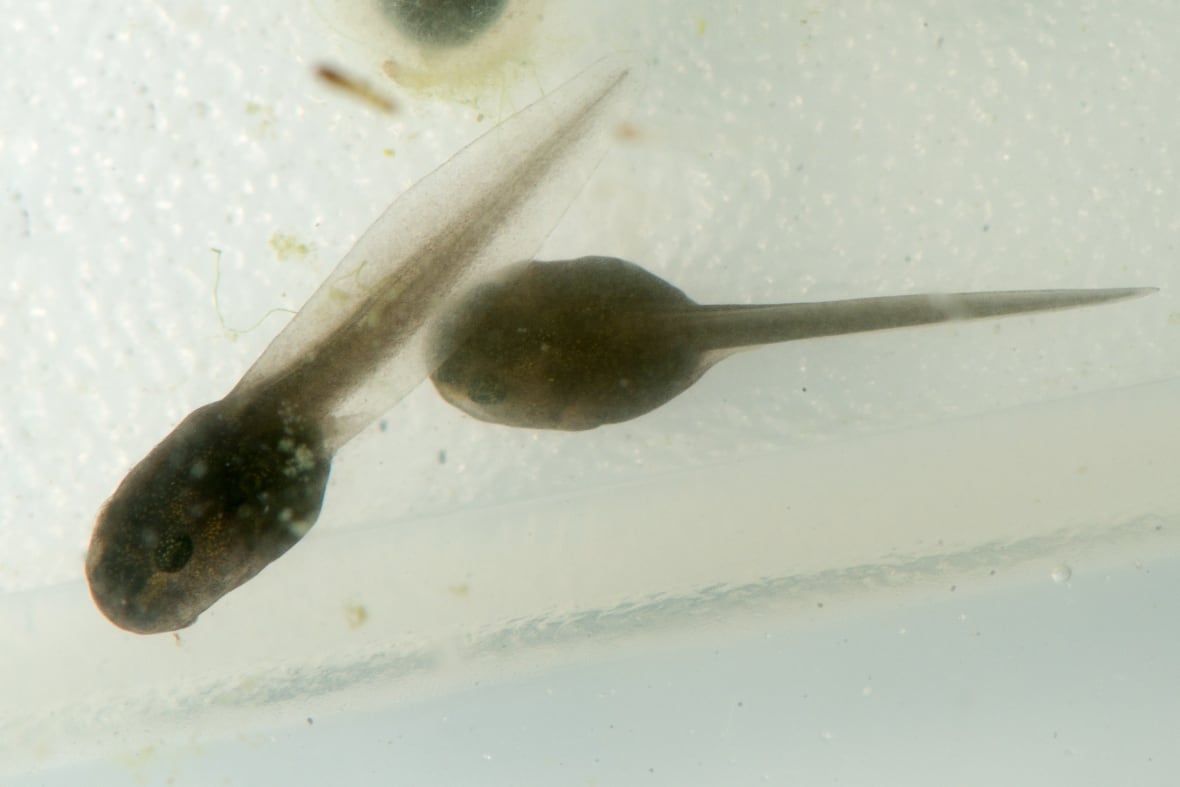

Between 2007 and 2010, and from 2013 to 2014, a total of 163,880 tadpoles were introduced as part of the translocation program.

“The growing sustainability we’re seeing in northern leopard frogs and their distribution might allow us to start saying, well, our population is recovering,” said Boukall.

Why did so many frogs croak?

The cause of the once-common northern leopard frog’s dramatic decline has not yet been confirmed by the province, Boukall said.

University of Alberta ecology professor emeritus Cynthia Paszkowski said there are “a lot of smoking guns” to consider when it comes to amphibian population declines.

“There’s a number of explanations for that, one being in some habitats, pesticides, herbicides, chemicals from the environment,” she said.

She pointed to other factors like disease, habitat destruction, and the stocking of fish into northern leopard frog habitats that previously had no fish, leading to limited oxygen in the water.

These factors can lead to fluctuations in amphibian populations across North America, Paszkowski said.

“Interestingly enough, there’s lots of areas in North America where the leopard frog has recovered from these historical dips,” she said. “But in Alberta, they really have not, and that’s why the province is trying to reintroduce them to areas where they think there’s still appropriate habitat.”

Paszkowski said the availability of suitable habitats in the frog’s historic range has been an advantage of the reintroduction program.

She pointed to three elements required for the frogs to establish successful self-sustaining populations: a breeding habitat, overwintering habitat, and then terrestrial habitat to feed in.

Alberta is home to eight frog species: the boreal chorus, Columbia spotted, northern leopard and wood frog, as well as the Canadian, Great Plains, plains spadefoot and western toad.