This story is part of CBC Health’s Second Opinion, a weekly analysis of health and medical science news emailed to subscribers on Saturday mornings. If you haven’t subscribed yet, you can do that by clicking here.

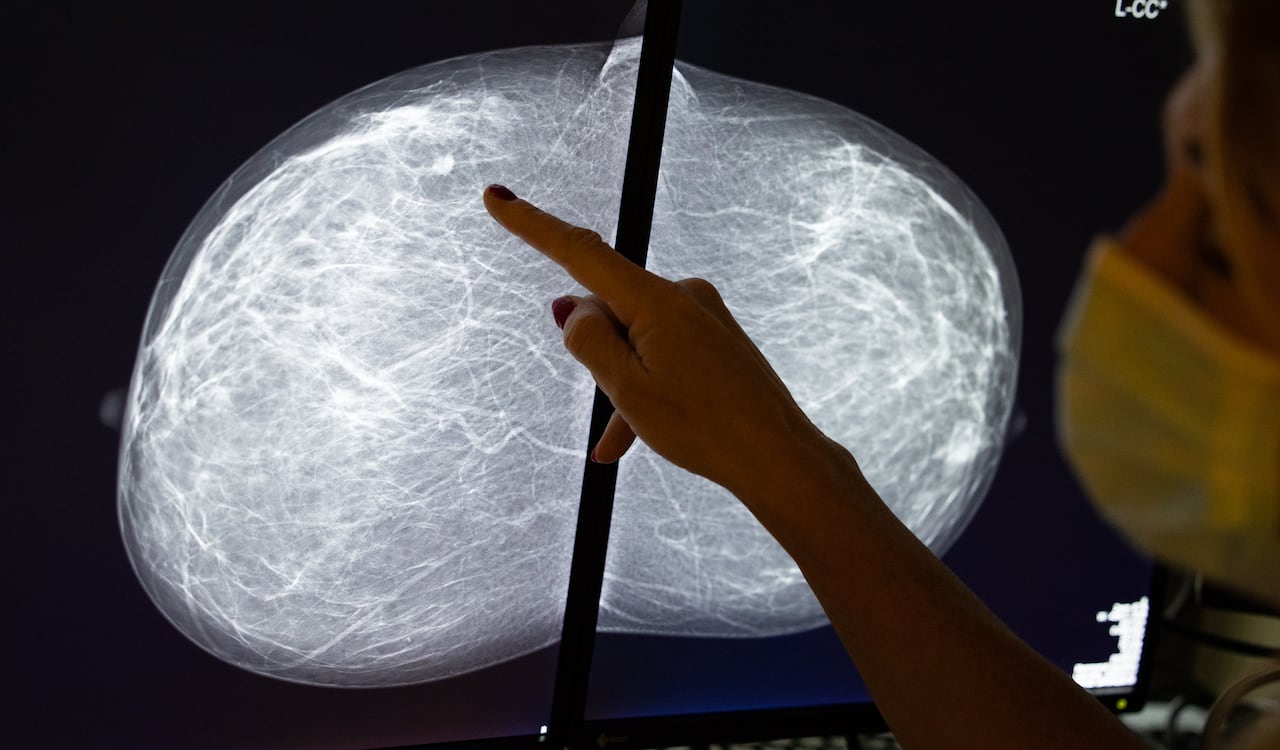

It’s been known for decades that breastfeeding and childbirth reduce the risk of breast cancer. Now medical researchers are gaining clues on why and hoping these insights could help create a pill to mimic the protective effects of nursing.

In October, researchers based in Australia found women who breastfed had more specialized immune T-cells in their breast tissue. Prof. Sherene Loi, a medical oncologist and the study’s lead author, likened the cells to “local guards, ready to attack abnormal cells that might turn into cancer.”

Loi hopes her findings could help prevent breast cancer in all women, regardless of whether or not they had children.

The study, published in the journal Nature, builds on past work that observed how pregnancy and breastfeeding are protective against the development of breast cancer with modern immunology to suggest a possible explanation why.

It’s an important question, according to Dr. Steven Narod, a professor of public health at the University of Toronto and director of the Breast Cancer Research Unit at Women’s College Hospital, who was not involved in the study.

Narod notes the Australian study doesn’t offer evidence of what the specific immune T-cells are doing in the breast. But if we start to understand how breastfeeding protects against cancer, that could lead to new treatments.

“We like the idea of breastfeeding as a way of preventing breast cancer, but we’d rather find a pill,” Narod said.

“If we really understood what it was, perhaps a hormone or something equivalent, maybe that could be used as a preventive treatment.”

Breast cancer in younger women

Some of the work on this question focuses specifically on young women — including those carrying mutations in tumour-suppressing genes known as BRCA genes.

When Narod and co-investigator Dr. May Lynn Quan in Calgary analyzed data from women in their 30s with breast cancer from across Canada, they found the disease often follows a poorer course than in post-menopausal women.

People with BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes that aren’t working properly due to mutations face increased risks of cancers including breast, ovarian and prostate.

Dr. Stephanie Wong, a surgical oncologist in Montreal with an interest in breast cancer prevention, studied breastfeeding after breast cancer in young BRCA carriers. Wong said she thinks it is important to understand the cellular and molecular building blocks underpinning breast cancer in certain women and its prevention in others.

The Princess Margaret Cancer Centre says it will be running a genomic study on up to 100,000 people in Ontario over the next five years, screening for genetic conditions that increase the risk of hereditary cancers and a condition tied to high cholesterol and heart disease.

“There is rarely one single risk factor that explains why one in eight women develop breast cancer,” Wong said in an email. “We usually think about a constellation of factors ― hormonal exposures, lifestyle factors, environment, family history, and genetics ― as playing a role in the development of the majority of breast cancers.”

Wong was quick to highlight not all women want to, or can have, children or breastfeed and it’s important to avoid shaming individuals. Women’s preferences and circumstances vary as do workplace policies, medical issues and support

Outside of breastfeeding, women can lower breast cancer risk through avoidance of smoking and excessive alcohol consumption while working out with aerobic exercise regularly and maintaining a healthy diet rich in fish and vegetable-based protein sources, Wong said.

What happens in the breast

Insights from studies like the one recently published in Nature could help researchers find new ways to prevent breast cancer in women aged 40 and under, said Christopher Maxwell, a professor of pediatrics at University of British Columbia.

“It is essential to understand this biology because it will both inform new ways to potentially prevent breast cancer and it may inform mothers about the biology of breastfeeding,” Maxwell said.

Maxwell likened the mammary gland to a fruit tree. During a menstrual cycle, breasts go through branching and budding in preparation for pregnancy.

“If a pregnancy occurs, you have blossoms and then the milk-producing cells,” he said.

After pregnancy, it’s as if the tree goes through winter.

Maxwell’s team and others have shown the immune system is essential to prepare a lactating gland and later “prune” the tree for winter — getting rid of abnormal cells.

“What we’ve seen is that in some situations, the pruning is less complete,” Maxwell said. “You have abnormal cells sticking around and these abnormal cells can then form these aggressive, triple-negative breast cancers.”

Triple-negative breast cancers are an invasive type. In the last 10 years, an immunotherapy has become standard treatment for it, Narod said.

Building a road map

By looking at cells in the lab, tissues from women donors, animal models of immune response and data from health records, medical researchers are looking for ways to improve the pruning to prevent breast cancer, Maxwell said. This week, U.S.-based researchers “painted the picture” to show cellular and molecular profiles of breast cancer in the journal Nature Aging.

“A breast cancer in a young woman does not look anything like a breast cancer in an older woman,” said Sandra McAllister, an associate professor at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“It’s not just that the immune system ages, but the immune system is different depending on the type of tumour in which it resides with age.”

Looking ahead in Canada, Narod, the Toronto breast cancer researcher, plans to dig into his hospital’s database of 6,000 women across the country who had breast cancer and BRCA1 mutation to look back at their breastfeeding practices.

“We’ve seen and we have heard that many patients have a baby after having breast cancer,” Narod said. “I think it would be interesting to see in those women whether those who breastfeed reduce the risk of the cancer coming back.”