It took months of mapping cases, dozens of locations sampled and weeks of lab sequencing to determine the likely culprit behind a recent outbreak of legionnaires’ disease in London, Ont. — one that killed four people and infected about 100 others.

It’s just the latest example of why it’s so difficult to pinpoint where the illness is spreading from.

Last week, health officials with the Middlesex-London Health Unit (MLHU) said the likely source of the outbreak was the cooling towers of a local meat-processing plant in the city’s east end. Health officials also determined the facility was likely linked to another outbreak last year that left two people dead and 30 others sick.

And in New York’s Harlem neighbourhood this summer, it also took weeks of meticulous searching to identify the cause of a legionnaires’ outbreak there, now linked to cooling towers from a hospital and a nearby construction site.

When it comes to tracking down the source of a legionnaires’ outbreak, experts say there’s a number of challenges standing in the way — from sampling potential sources to actually testing for the bacteria.

“It’s been shown that a source for an outbreak for legionella isn’t found in 50 per cent of cases,” said Dr. Joanne Kearon, the MLHU’s associate medical officer of health.

“It’s not like a food outbreak … where all of these people may have been in one place and have been exposed in the same place. They may have all actually been exposed in different places, [because] legionella travels in the air.”

A source has gone undetected in past outbreaks in Canada, including ones in recent years in Quebec and New Brunswick.

Bacteria causes ‘atypical pneumonia’

Legionella bacteria are naturally found in freshwater, like lakes and streams, as well as soil. Typically, the amount of bacteria in the environment isn’t enough for people to get sick, according to the U.S.-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The bacteria becomes problematic when it grows in standing water of human-made systems, such as cooling towers, water tanks, even swimming pools or hot tubs. If the contaminated water gets sprayed or misted into the air and people breathe it in, that’s when they can get sick.

Some people will get a mild sickness, called Pontiac fever, which usually includes symptoms of fever and headache, and often goes away on its own.

Legionnaires’ disease is a more severe form of the respiratory illness that shows up as an “atypical pneumonia” and usually impacts older people with weakened immune systems, said Dr. Philippe Lagacé-Wiens, a medical microbiologist at St. Boniface Hospital in Winnipeg.

“You’ll find patches usually on both lungs, which is again, unusual,” said Lagacé-Wiens, who is also an assistant professor at the University of Manitoba.

Symptoms of legionnaires include shortness of breath, fever, cough, phlegm, and sometimes muscle aches and diarrhea, he said. The sickness is not transmitted from person to person.

“People with weakened immune systems can actually have a pretty serious illness and actually end up in the intensive care unit,” he said.

Cooling towers a common culprit

Past outbreaks have been linked to hot tubs, spas and even decorative fountains.

But most often, large outbreaks are the result of cooling towers, part of the HVAC systems often found on the roofs of industrial buildings and highrises, which use fans to cool water and help remove heat from the buildings.

If legionella grows in that water, the fans can then create aerosols and spread the bacteria in the surrounding area.

“The aerosols can actually travel many kilometres,” said Vincent Brown, a technical adviser with cooling tower maintenance company Magnus.

“So if the system is not well maintained, the infections can be actually several kilometres away from the source, which is one of the reasons why it’s difficult to actually find the source.”

Research has shown that those aerosols can travel up to six kilometres away. And outbreaks occur more frequently during periods of warm weather.

Like finding a ‘needle in a stack of needles’

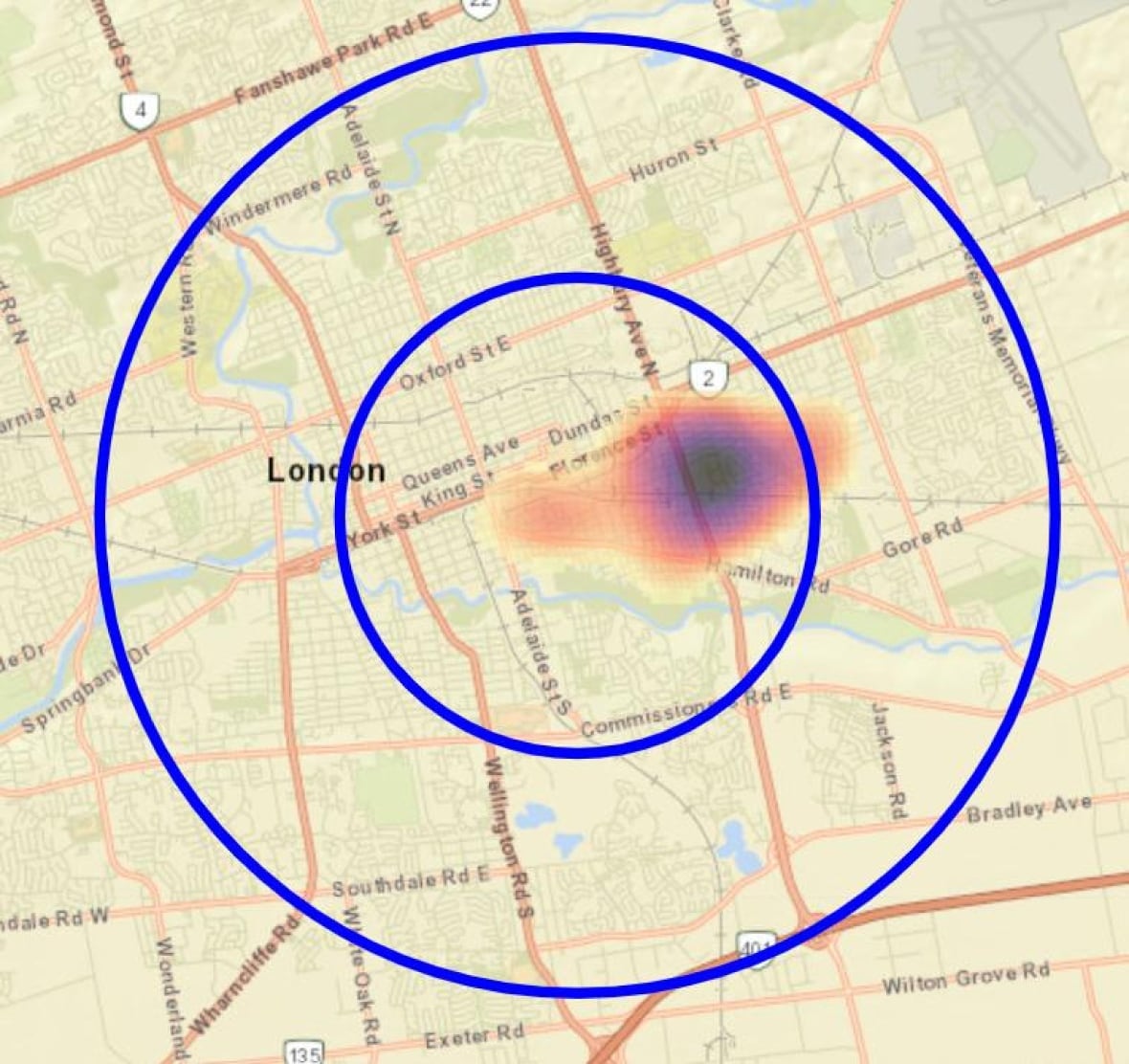

When it came to the outbreak in London, Ont., many of the cases were concentrated in an area with dozens of cooling towers. But based on where the cases were, health officials narrowed their search to a three-kilometre radius.

“In London, there’s simply so many potential sources. It’s [like finding] a needle in a stack of needles,” said Kearon.

One of the issues Kearon and her team ran into was knowing where every cooling tower was, in order for them to be tested.

“We don’t have a list of every single place that has a cooling tower. So we have our inspectors — literally — walking the streets, driving around, on top of buildings with binoculars, trying to identify where potential cooling towers are,” she said.

Sampling the cooling towers is another tedious task, said Kearon, with it taking about half a day to test a single location.

And when a legionnaires’ outbreak is declared, building owners will often rush to disinfect their systems, she said.

“They will put in a lot of chlorine … to attempt a chemical disinfection,” said Kearon, adding this can temporarily mask the presence of legionella.

“But without that step of manually, physically cleaning and scrubbing the walls of the system, a biofilm can grow back.”

A biofilm is when bacteria attach to a surface with a protective coating, which often makes it chemically resistant.

London MorningA warmer climate could lead to more Legionnaires’ outbreaks

London is dealing with a Legionnaires’ disease outbreak, something that’s is happening more frequently across North America and Europe. Joan Rose, the director of the water alliance at Michigan State University, joined London Morning to talk about how the bacteria spreads and what can be done to prevent future outbreak situations.

Even when a cooling tower sample does test positive for legionella, it might not be the exact bacterial subtype that’s making people sick.

“Just because we find legionella bacteria in one environmental source and somebody is sick in that same geographical region … doesn’t mean that those two are linked,” said Lawrence Goodridge, a microbiology professor at the University of Guelph.

“We have to show that the two strains of the bacteria are identical or are highly similar to each other.”

During the investigation in London, for example, multiple cooling towers at nine separate locations tested positive for live legionella bacteria, the MLHU has said.

What happens in the lab?

These positive samples were handled by Public Health Ontario. The organization’s lab staff grew the bacteria and looked at its genetic makeup. Then they checked to see if those samples matched what people are getting sick with.

That whole process can take a few weeks, experts say.

“You will likely identify legionella in many environments, but again, it’s all about making that match between clinical cases and the environmental sample,” said Shawn Clark, a Public Health Ontario clinical microbiologist who was testing samples for the outbreak in London, Ont.

In total, the MLHU collected 160 samples from 49 different cooling towers.

In late August — seven weeks after the recent outbreak was first declared — the MLHU confirmed it had found a match and was working with the meat-processing plant identified to properly clean out its cooling towers.

Ontario’s Ministry of Health didn’t confirm whether the company would face any consequences for the outbreak. Following previous outbreaks in Canada, those affected have filed lawsuits.