Newfoundland parent Scott Chandler jokes that September is usually a whirlwind he “kind of dreads,” between juggling the back-to-school season for his son Rhys and restarting a host of his extracurriculars, like hockey, karate and swimming lessons. This year, however, he’s looking forward to the normalcy of that busy schedule.

They’ve been caught in a different sort of whirlwind since his family lost their home as well as Rhys’s school Cabot Academy in the Conception Bay North wildfires in early August.

Following local orders, they’ve decamped three times in mere weeks: from an evacuee centre in Victoria to another in Carbonear to a third in Harbour Grace.

It’s been “heartbreaking” explaining to his third-grader “all your clothes, your stuffies, your games, your video games are gone. He’s processing it like an eight-year-old does,” Chandler said.

While he says Rhys is looking for silver linings — like reuniting with friends at Carbonear Academy, where some students have been reassigned for the time being, or being closer to hockey team buddies living nearby — Chandler just hopes for as regular a September as possible for the youngsters.

“They need normalcy. They need that routine. They need to be together.”

Yet another season of record-setting wildfires is disrupting the return to school for some communities in Canada, though the impacts differ depending on region. Schools boards need multi-level support to prepare and regularly update emergency response plans, some experts say, so that if disasters happen, kids get back to class as quickly as possible.

New environmental disruptions

In times of emergency, schools are among the first community supports mobilized — from offering up buildings capable of large gatherings to loaning school bus fleets for rapid evacuations, says Alan Campbell, president of the Canadian School Boards Association.

However, one big takeaway from the past few years, Campbell says, is that when emergencies like wildfires call for evacuations, it’s imperative for educational officials keep track of and maintain communication with families amid the chaos. That way, no matter where they end up, evacuated students can easily access schooling again.

Campbell, a trustee in the Interlake School Division northwest of Winnipeg and also president of the Manitoba School Boards Association, pointed to recent cases in Winnipeg and Brandon as good examples.

He noted that local school divisions and the province are maintaining contact with wildfire evacuees still living in hotels a week ahead of the new term, to connect them with nearby public schools their kids can attend in the meantime.

Canadian school officials have plenty of experience responding to snowstorms, according to Campbell, but wildfires, poor air quality and extreme heat are now also realities for education leaders to grapple with.

“When it comes to monitoring air quality … based on the movement of wildfire smoke, that will just as much now become part of planning considerations as is blizzard forecasting,” Campbell said.

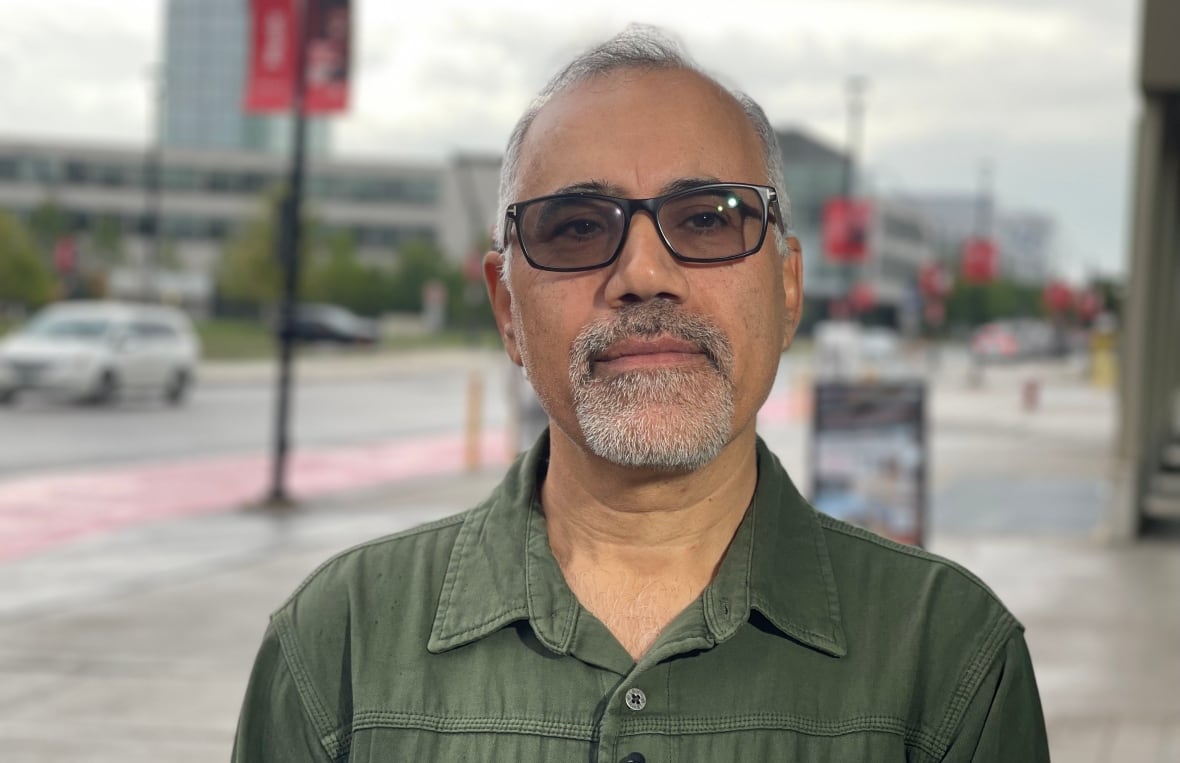

With the large role schools play in society, it’s very important for them to be ready for emergency situations and able to continue operations safely, says Ali Asgary, a professor of disaster and emergency management at York University in Toronto.

School boards, divisions and districts do typically have emergency management plans — on paper, he says.

The reality is, however, that not everyone is necessarily aware of what to do when an emergency hits, whether that’s staff, families or students.

Procedures and plans should also be regularly updated, he added, given how dynamic the school environment is.

Asgary wants to see schools and school boards “practice” their different emergency response protocols — as they do when running through fire drills or lockdown procedures with students, for instance — to ensure the disaster plans function as intended.

“We don’t want to lose time. Even one day, two days, one week of losing school for children is a huge gap, a huge loss. We want to minimize that.”

Multi-level support, investment needed

Both Campbell and Asgary say investment from multiple levels of government is also needed to ensure Canada’s school systems are able to properly prepare for disasters and mobilize quickly if they happen.

“We cannot expect schools at the local level to have the resources to arrange all these things themselves,” Asgary said. “There has to be some supports from upper levels, up to federal level support.”

Dr. Peter Silverstone, a professor at the University of Alberta, outlines mental health considerations school officials and parents must keep in mind as kids head back to class after a disaster like the Jasper wildfires.

Federal support of emergency management in schools makes good sense, provided provincial, local and school-board decision-making is preserved, Campbell noted, since they’re closer to and more knowledgeable about what particular communities need.

“That sort of multi-level collaboration is going to have to become more a part of how we respond to some of these issues,” he said.

Back in Newfoundland, concerned dad Chandler is thankful school leaders acted quickly to redistribute Cabot Academy students and teachers to two other schools so “they’re ready to hit the ground running” after Labour Day.

Still, he’s hoping there will be ongoing investment and support for affected students as time goes on — and for a reunion sooner than later.

“Bring in some child psychologists. Bring in some behavioural therapists, because we’re going to have those problems. I foresee that,” Chandler said.

“I really hope [officials are] looking at it from all angles and taking everything into consideration to keep these students together and — especially — keep the staff because … they need each other. They need to talk. They need to grieve together.”