What On Earth29:51Bats vs. wind energy: a gory tale of two climate solutions

Bats don’t exactly have a glowing public image. After all, they’re associated with blood-sucking vampires, gloomy caves and all things spooky.

But researchers say migratory bats in Canada are in desperate need of protection because wind turbines have been slaughtering their populations for decades.

“We are not talking about if these migratory bats go extinct. We are just talking about when,” said Cori Lausen, director of bat conservation with the Wildlife Conservation Society, based out of B.C.

Lausen and other experts say there are solutions that can help stave off further destruction of bat populations, including curtailing how often the deadly turbine blades operate. And she says it’s not just bat lovers who should pay attention.

There are three migratory bat species in Canada: the hoary bat, eastern red bat, and silver-haired bat. All three are endangered, according to Canada’s Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife. The federal government is reviewing whether to add them to the Species at Risk Act.

According to a paper published in Biological Conservation in 2017 , the hoary bats’ population could drop between 50 and 90 per cent in the next 50 years, and could go extinct within the century.

Realizing the problem

Lausen first saw how much danger wind turbines posed to bats back in the early 2000s, when she was studying bats at the University of Calgary.

TransAlta, the company operating one of the first wind energy projects in Canada, asked her lab supervisor to investigate after dead bats were found around their turbines near Pincher Creek, 200 km south of Calgary.

“Seeing the dead bats is really hard because these are long-lived mammals that can’t withstand these high fatality rates. And you had this gut feeling like, this is going to be a problem,” said Lausen.

Though at the time they didn’t count exactly how many bats died, most were killed after being hit by the blades, while others died because of the pressure change near the turbines.

But it wasn’t clear why they were getting so close to the turbines in the first place.

Lausen said they could be checking out the turbines out of curiosity, or their echolocation bounced off the turbines in strange ways, sending them in blind.

Their six-week migration also coincided with their mating season, and the bats might have mistaken the towering turbines for trees where they could find a mate.

Whatever the reason, one thing was clear: bats were dying.

Why bats are important

Bats are hugely important for farmers and ranchers. They devour all sorts of insects, giving farmers the option not to use pesticides on their crops or grasslands.

“I cannot imagine what the insect population would have been if there hadn’t been this population of bats,” said Julia Palmer, a rancher in Pincher Creek, Alta.

According to a research paper published in the journal Science in 2024 , a die off in the bat population often led to farmers having to use more pesticides. Higher rates of infant mortality also followed.

Though the paper was examining deaths caused by white-nose syndrome, Lausen says the research offers a warning about what is at stake.

“This is the first piece of evidence where we’ve been able to point and say, ‘See, we told you, bats are important for your health,'” said Lausen.

What is being done

Following the slew of bat fatalities and an uptick in windfarms, Lausen and her team proposed a solution that would become known as curtailment, or the act of pausing wind turbines.

Bats often fly when it’s not very windy, so during those times, the turbines could be shut off with little impact on profit, she said.

She also suggested shutting off turbines when bats were on their migration and passing by wind farms.

According to research in Alberta published in 2022, seasonal overnight stoppages would decrease profits by less than two per cent, but prevent many bat deaths.

In 2013, Alberta published its first guidelines for wind energy projects and migratory bats, implementing the curtailment suggestions made by Lausen and her team. In 2017, another directive limited the number of bat deaths allowed at a wind turbine.

Some other provinces also have rules around a bat-death threshold, or a minimum curtailment level, but it differs from place to place.

Companies don’t currently face any penalties if they reach those thresholds, Lausen says. Instead, they’ll be required to amp up their curtailment efforts to prevent future deaths.

Lausen says this isn’t enough, because there are so many more wind turbines now compared to a couple decades ago. Since the thresholds are per-turbine, it can still equal a lot of deaths.

According to a report from the federal government, Canada’s wind power capacity has skyrocketed since 2007.

“Just even setting these thresholds has not worked out well, honestly, because the big picture isn’t being considered,” she said.

Smart curtailment

Kent Russell says says turbines can be designed to only shut down when bats are expected to be around, rather than shutting them off for long periods of time.

One way of doing this is a device that can hear the bats when they are nearby, then turn the turbines off until they pass.

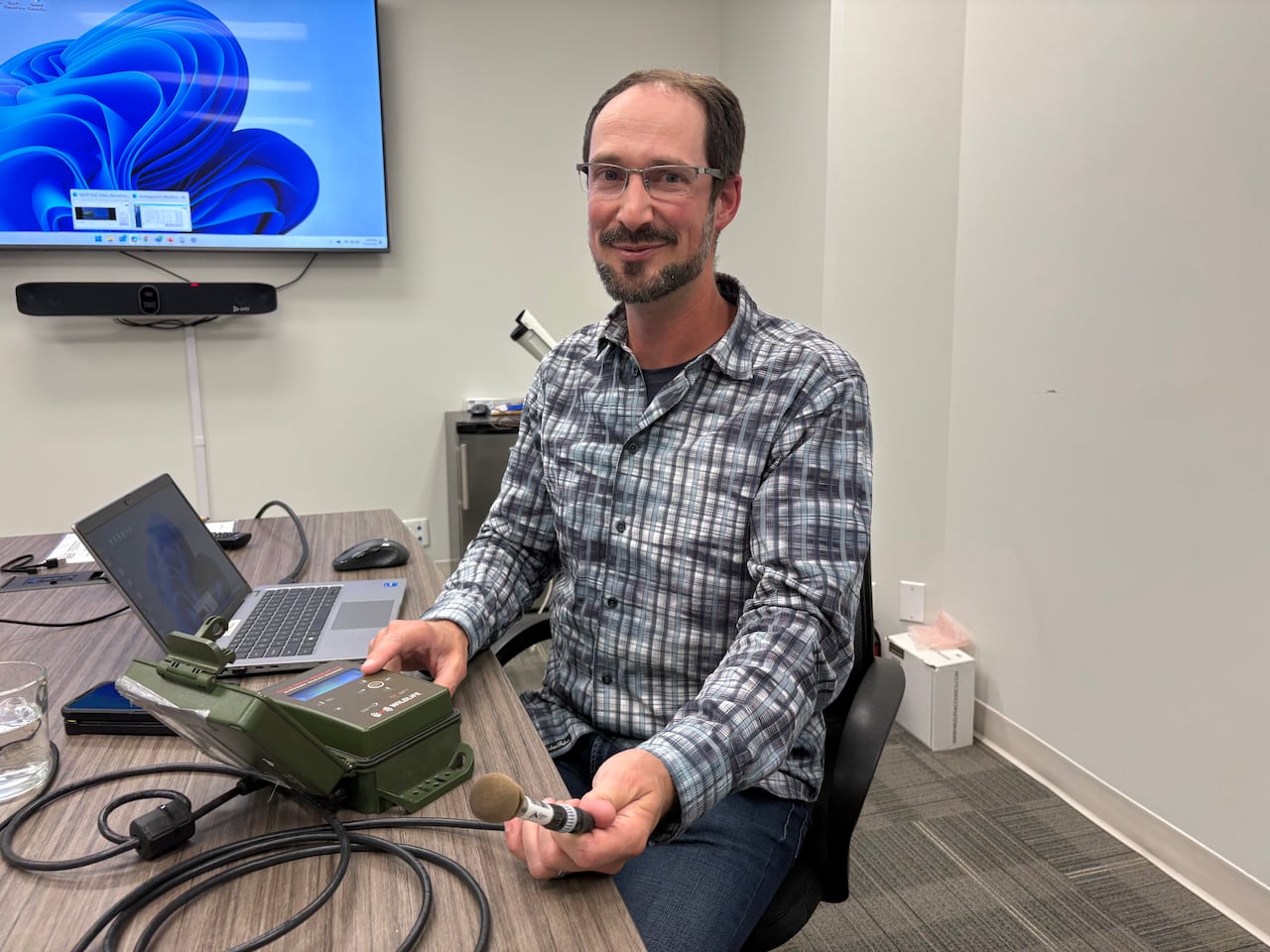

Russell is a senior wildlife biologist and project manager with Western Ecosystems Technology Inc., which has headquarters in Calgary and Wyoming.

His company works with wind energy companies to study bat activity throughout the year, then creating models that predict the best times to shut down a turbine.

“It’ll be a single set of rules that would get programmed into the turbine so that the turbines turn on and off through the night as the schedule prescribes,” said Russell.

White-nose syndrome has already decimated bat populations across eastern Canada. Now, as the fungal disease threatens to spread west, one scientist is fighting back with a probiotic ‘cocktail. CBC’s Camille Vernet went to meet the scientist and the bats she wants to protect.

Sarah Palmer, a former director for a wind project owned by Toronto-based renewable energy company Potentia, says smart curtailment is key for getting industry on board.

“What industry is looking for with the new technologies is for provinces to accept these new types of technologies as an option instead of blanket curtailment,” said Sarah Palmer (no relation to Julia Palmer).

Smart curtailment technologies are regulated from province to province, and existing research comes out of the U.S., so it can take time for regulators in each province to approve its use. And some turbines are just too old to use the technology.

As more research is done to learn about bats’ migration and population, Lausen says regulators should prohibit companies from building wind farms along migratory routes.

“The hope that we can keep these bats from extinction is what keeps me going,” she said.

“Hopefully we can keep these bats alive long enough to advance technologies for renewable energy to the point that maybe we won’t kill bats anymore.”