Day 6Worldwide shortage of hormone replacement therapy leaves women struggling

The long list of symptoms of perimenopause and menopause range from inconvenient to debilitating. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) can be a huge help, but a worldwide shortage of HRT is leaving women in the lurch. Alison Shea, an Assistant Professor in Obstetrics and Gynecology and Psychiatry at McMaster University explains why the shortage is so problematic.

Karen Golden can vividly recall the symptoms of menopause she experienced during a shortage of her hormone replacement therapy (HRT) medication five years ago.

“It wasn’t a good time,” recalled the Toronto-based lawyer. She had started undergoing HRT to deal with sleep issues and anxiety related to menopause several years ago.

But in 2020, there was a shortage of the medication she was taking. Her doctor tried to switch her to other products, but they caused side-effects, so Golden made the decision to go off HRT altogether and the symptoms returned.

Golden is one of many women around the world who have been affected by worldwide shortages of HRT medications, used to help manage menopausal symptoms. The shortages have left women in the lurch, unable to find relief from symptoms that range from inconvenient to debilitating.

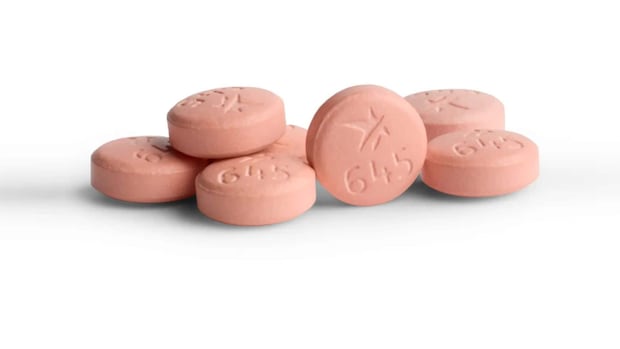

Drug Shortages Canada, an online database of drug shortages and discontinuations in the country, shows that since 2017, there have been 92 shortages and four discontinuations of products containing estradiol, a form of estrogen commonly used in HRT drugs. The products include transdermal patches, pills, vaginal rings, topical gels and creams.

“If the woman can’t get her medication, she’s not going to be functioning as well. She’s not going to be sleeping. Her mood may drop significantly,” Dr. Alison Shea, an obstetrician-gynecologist and assistant professor at McMaster University, told CBC Radio’s Day 6.

Menopause occurs 12 months after a woman’s last menstrual period. Perimenopause, the stage leading up to that, comes with hormonal changes that last an average of seven years, but can be longer for some. During this time, many women experience hot flashes, night sweats, trouble sleeping, changes in mood and libido, or difficulty concentrating — symptoms that can be treated by hormonal therapy.

HRT shortages also put a burden on doctors and pharmacists, Shea said, since they have to spend extra time looking for alternatives for their patients — adding stress to an already overloaded health-care system.

“So really, it’s chaos for everyone,” she said.

According to a written statement from Health Canada, at the moment, HRT drugs are generally available in Canada with the exception of estrogen/progestin patches. The estimated end date of this shortage is July or August.

A new review of menopause research suggests doctors reconsider hormone therapy as a treatment option for healthy women under 60. Recent studies have shown that previous health concerns about such treatments were overstated.

‘Dangerous and unethical’

Meanwhile, some women who rely on these medications feel the shortages aren’t being adequately addressed and worry their health is not being taken seriously.

Though Golden stopped taking HRT due to the 2020 shortage, she was able to go back on her original medication last year. But after just a few months, she learned it was again on back order.

As she was running out of her medication, she reached out directly to the pharmaceutical company behind the drug. They told her that they were fulfilling orders in “an equitable way” and that it would take some weeks to stabilize.

Golden didn’t accept that response. After some back and forth with the company, they agreed to ship some stock to her local pharmacy.

But she doesn’t think other women should have to go to such extremes to have reliable access to HRT drugs.

“It would be helpful if the decision-makers in this knew that giving people medication for their physical and mental health and then yanking it away is dangerous and unethical,” she said.

A complex supply chain

Mina Tadrous, a pharmacist and associate professor in the facility of pharmacy at the University of Toronto, said it can be complicated to pinpoint the exact source of a shortage.

Drugs often pass through multiple countries and several different facilities before reaching Canadian pharmacies, he said.

“If anything along that supply chain breaks, it sort of feels like a slow-moving train because it takes a few weeks or months for it to hit,” Tadrous said.

Also, manufacturing hormones is particularly specialized, involving specific chemical reactions and careful handling of sensitive molecules.

“You have a product that’s a little harder to make, and then all of a sudden, you also have very few companies that are active in the marketplace,” he said.

Producing a drug can take anywhere from 18 to 24 months — from sourcing raw materials to production to quality control to distribution, said Christian Ouellet, vice-president of corporate affairs at pharmaceutical company Sandoz Canada, which produces a range of HRT products.

“Manufacturing a molecule is not like manufacturing bread — it’s complex,” he said, noting that manufacturers always want to meet quality, efficacy and safety requirements.

Though there have been shortages of HRT drugs from Sandoz Canada over the last few years, Ouellet said the company is currently meeting demand.

In a written statement, Health Canada spokesperson Mark Johnson said when drug shortages happen, it “works closely with manufacturers, health-care providers, and provinces and territories to monitor the situation and explore shortage mitigation options.”

With HRT drugs specifically, shortages are driven primarily by a recent surge in demand, which Ouellet said is “several times more than what it was five years ago.”

According to aggregate claims data from Manulife, one of the top insurance providers in Canada, there was a 21 per cent increase in the number of women aged 45 to 65 seeking HRT for menopausal symptoms from 2020 to 2023.

CBC Newfoundland MorningResearch shows that hormone replacement therapy is not as risky as once thought for menopausal women

For years, women in early menopause who experienced uncomfortable symptoms, such as hot flashes, had been told not to use hormone replacement therapy (HRT). It had long been suspected of causing an increase in the risk of developing breast cancer. But further research has proven that’s not true. Garnet Anderson is a scientist with the Women’s Health Initiative, based out of the University of Washington. She spoke with CBC’s Leigh Anne Power.

Expanding HRT use

Several experts point to social media and greater advocacy among women for their own health as factors driving demand.

A 2002 study linking HRT drugs to increased instances of breast cancer and heart disease has also been debunked in the last decade, resulting in more doctors prescribing them.

Many of these medications are also prescribed in gender-affirming hormone therapy. According to Dr. Kate Greenaway, medical director of Foria, a virtual clinic providing gender-affirming care, these shortages “can be a little more profound” for the trans and non-binary community, because of the limited number of alternatives in Canada.

There have also been shortages of other hormones used in gender-affirming care, she said, such as androgen blockers and testosterone, and it’s difficult to predict which products will become scarce and how long the shortage will last.

Tadrous said he’s skeptical that we’ll see the end of HRT shortages without major action, like bolstering production or giving pharmacists the authority to replace a therapy that’s not available with another equivalent drug or combination of drugs.

Despite the fact that demand for HRT has grown, it’s still a relatively small market compared to other drugs, Tadrous said, noting that increasing the market size for HRT drugs — in other words, prescribing it to more women — might actually incentivize manufacturers to ramp up production overall.

“If we actually used it more often, then the pharmaceutical companies would want to make more,” he said.

The menopause movement is heating up, empowering women to talk more openly about their symptoms and demand treatment. CBC’s Ioanna Roumeliotis steps into the world of menopause advocacy and uncovers a passionate community fighting a system that unfairly sidelines women’s health.

Some menopause specialists do want to see access to HRT drugs expanded.

Dr. Michelle Jacobson, a gynecologist who sits on the board of the Canadian Menopause Society, thinks every woman who is of average age for menopause, doesn’t have other major health issues, and is experiencing symptoms like hot flashes and night sweats should be offered hormone therapy.

“That is agreed upon by every guideline and every organization out there who have opinions on menopause,” she said. But she adds that some physicians are still hesitant to prescribe hormone therapy — sometimes just from a lack of knowledge.

“We shouldn’t let our biases get in the way of what all of the organizations and Health Canada are telling us is appropriate.”